Search results3 results

MUSEUM

Switzerland, Basel

The Pharmacy Museum of the University of Basel (Pharmaziemuseum Universität Basel) is one of the largest and most important collections of historical pharmaceutical artifacts in the world, the only one of its kind in Switzerland. Its collection includes apothecary ceramics, fully preserved apothecary furniture, an alchemical laboratory, mortars, traveling apothecaries and surgical instruments, medical books, historical medicines and devices related to drug production. Museum is located in the heart of Basel's old town in the Zum Vorderen Sessel building, first mentioned in 1316. Over time, it has hosted notable figures such as Johann Amerbach, Johann Frobenius, Erasmus of Rotterdam, and Hans Holbein the Younger. In 1526-1527, the renowned Theophrastus von Hohenheim (Paracelsius) worked here, and his famulus Johannes Oporinus who later published Andreas Vesalius' groundbreaking anatomy book De fabrica corporis humani as well as works of Paracelsius.

Italy, Padua

Bo Palace (Palazzo del Bo) is the central piece of the Paduan University. Established in 1222, the University of Padua is one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in the world. Its Medical Faculty has been a leading institution for medical studies for centuries. Perhaps the most famous alumnus of the Medical Faculty is Andreas Vesalius, who is often referred to as the father of modern human anatomy. He studied and later taught at Padua, and his seminal work, "De humani corporis fabrica" (On the Fabric of the Human Body, 1543) was a groundbreaking text in anatomy. The Anatomical Theatre of Padua, built in 1594 during tenure of Girolamo Fabrici d’Acquapendente, is the oldest surviving anatomy theatre in the world. It was here that many important dissections and lectures took place, attracting students from across Europe is the place for 16th-century Anatomy Theatre. Another famous alumni of the University was William Harvey, who discovered blood circulation.

Articles

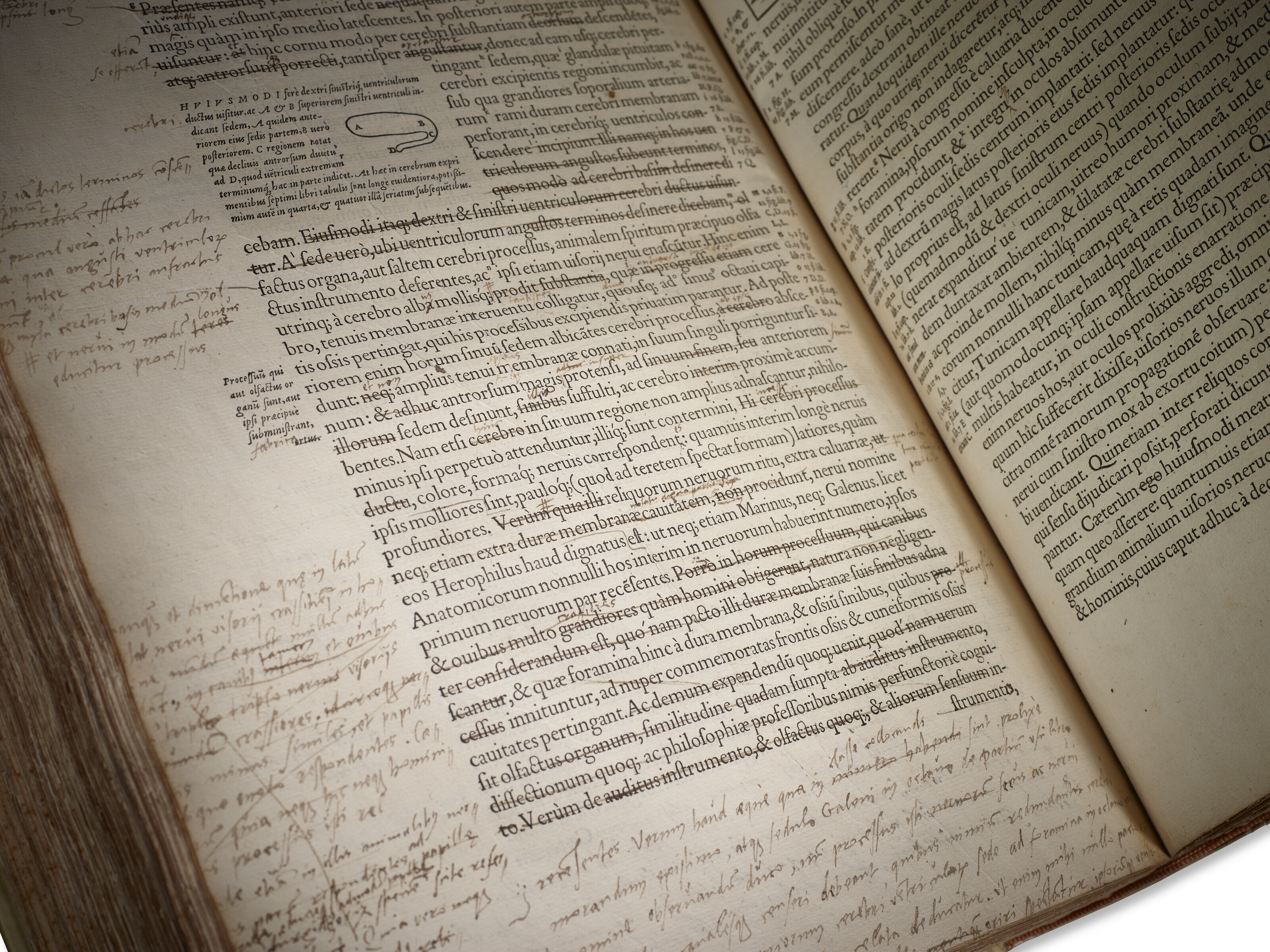

The story of how the second edition of the book De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, by Flemish Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), desecrated by numerous marginal notes, became one of the most outstanding examples of scientific printing that has come down to us has shocked the world of medical history and bibliography. This book, first published in 1543, then revolutionised anatomy and, among of others, commented on about 200 mistakes and misconceptions of the infallible authority, Claudius Galenus, questioning more than a thousand years of anatomical beliefs. It is no wonder that the young genius (Andreas Vesalius was only 29 years old when by publishing his Opus magnum) faced not just significant opposition, but fierce hatred, a real mass shitstorm for questioning established views, rocking the comfortable chairs of professorial chairs.