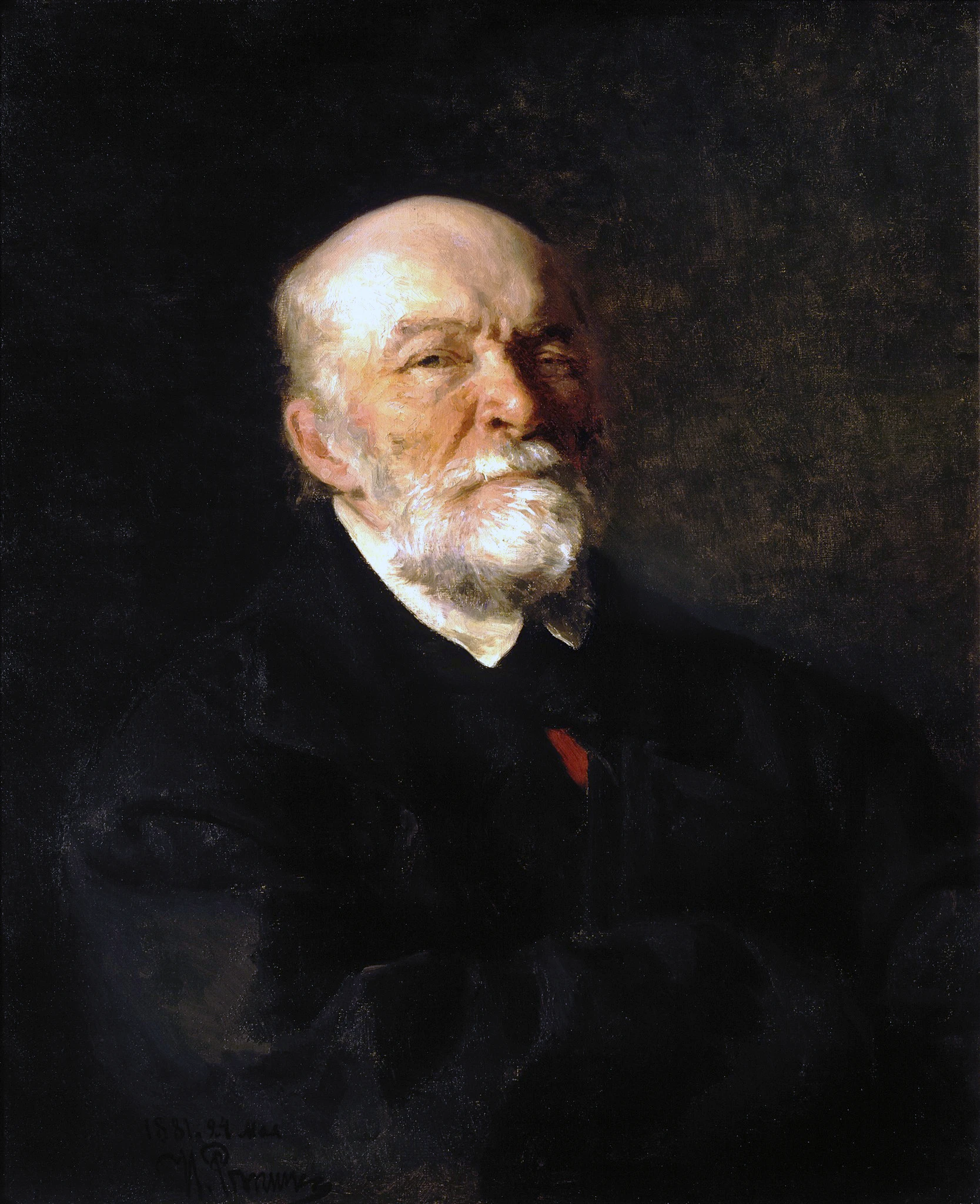

Paré, Ambroise

Ambroise Paré (born ca. 1510, Laval, France, died 20th December 1590, Paris, France), considered to be 'père de la chirurgie française' (the father of French surgery), royal surgeon to four kings. Born in the French province, he revolutionised surgical practice despite having developed only a few entirely original methods (mostly reintroduced old back into practice). Paré's status as the ‘father of French surgery’ is not due to individual inventions, but primarily to the fact that, thanks to royal support, his voice could not be ignored. His revolutionary methodology for the time included empirical observation (instead of reading the classics), challenging dogma (rather than commenting on ancient authors), democratising knowledge (books in vernacular French rather than scholarly Latin) — thanks to his numerous widely circulated publications richly illustrated, his ideas and concepts found their target audience and drowned out the opinions of conservative opponents, while the status of surgeons was raised from that of modest craftsmen to the noble authority of university medicine.

Main Dates

1510: (?), Ambroise Paré was born in Bourg-Hersent, near Laval, into the family of a chest maker. Ambroise was one of four children in the family. His older brother, Jean Paré, was a barber-surgeon in Vitré, where Ambroise learned the basics of his craft.

1529: continued his training as a surgeon at the Hôtel-Dieu, where he worked as an assistant surgeon for three years. After completing his studies, he entered the service of Baron René de Montjean, Lieutenant General of the Infantry, undoubtedly for financial reasons.

1536: became maître barbier-chirurgien.

1537: Participated in the Battle of Suse Pass (Eighth Italian War). There he performed his first elbow exarticulation and discovered that arquebus powder did not poison wounds, as many believed, so wounds could be treated with turpentine and egg yolk instead of boiling elderberry oil.

30 June 1541: He married Jeanne Mazelin, daughter of the barber of the chancellor, and had four children from this marriage.

1542: Participation in the Siege of Perpignan. Successful treatment of a shoulder wound sustained by Marshal de Brissac.

1544: Siege of Boulogne, successful operation by François de Lorraine, Duke of Guise, who was seriously wounded by a spear blow to the face.

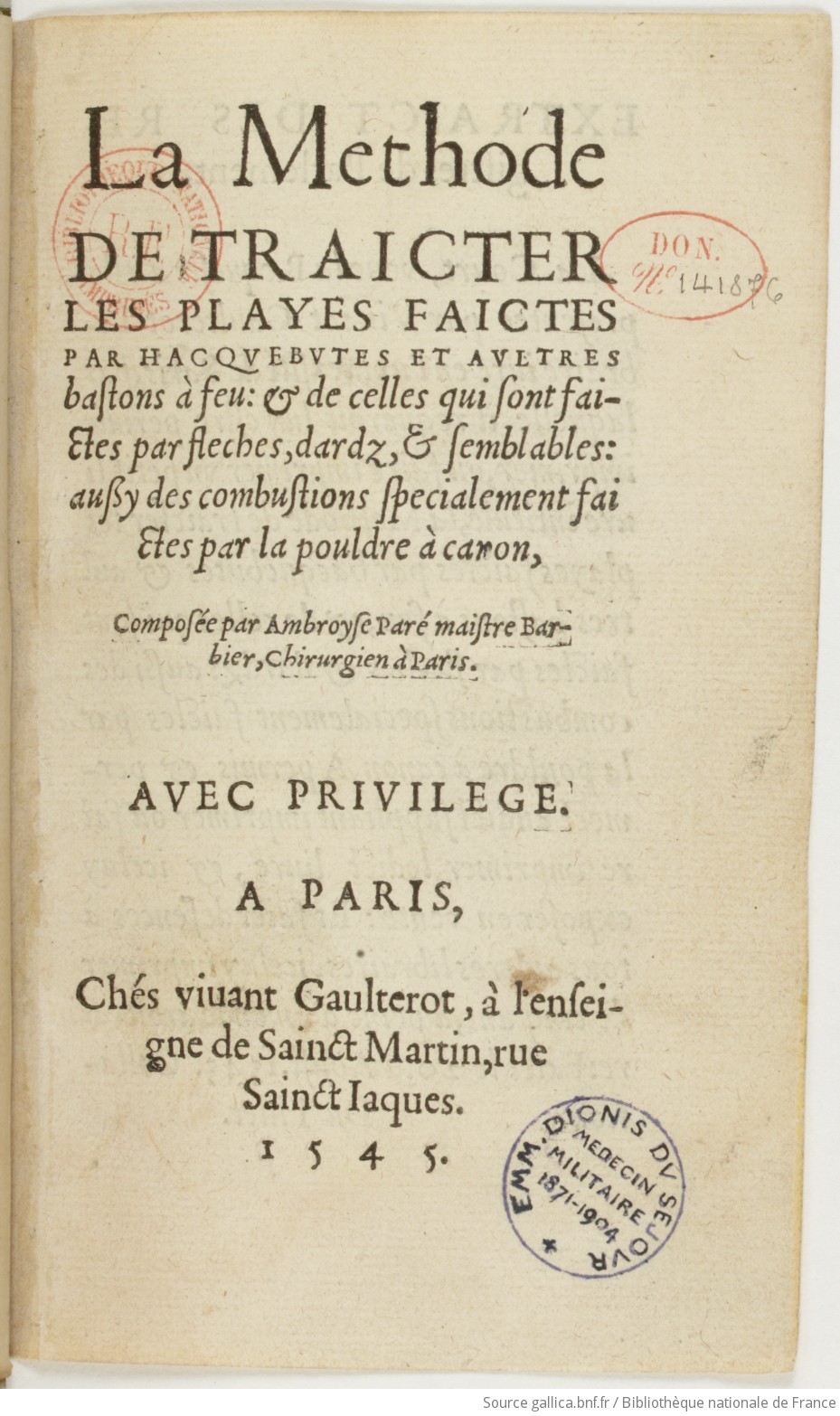

1545: Publication of La Méthode de traicter les playes faictes par hacquebutes et aultres bastons à feu (The method for treating wounds caused by arquebuses and other firearms…) — first surgical manual originally written in French.

1552: Ambroise Paré began his service to Antoine de Bourbon, King of Navarre.

1552: Participated in the Siege of Metz

The entry of King Henry II of France into Metz marks the end of the Metz Republic (1552), Auguste Migette, 1864, Musée de la Cour d’Or, Metz, France

1553: Paré was taken prisoner during the Siege of Esden, but even as a prisoner he continued to treat the wounded. He was released after the end of the military conflict and returned to France.

8 December 1554: Ambroise Paré was awarded the title of Master of the Confrérie de Saint-Côme et de Saint-Damien, an association of barber-surgeons that had existed since the 13th century, known as ‘surgeons in long robes’ (chirurgiens de "robe longue"), who, unlike ordinary barbers and bath attendants, had to pass a pear professional examination.

1 January 1562: Catherine de Medici appointed him first surgeon to King Charles IX.

The painting ‘The Death of Charles IX’ depicts him dying of pleurisy, which developed after tuberculosis pneumonia. Next to him are his mother, Catherine de Medici, and his wife, Elisabeth of Habsburg, Archduchess of Austria. The painting 'La Mort de Charles IX', 1834 by Raymond Auguste Quinsac Monvoisin (1794–1870), oil on canvas, 233 x 291,5 cm, presented in the Musée Fabre, Montpellier, France. Credit: wikipedia.org

1564: Paré published Dix livres de la chirurgie: avec le magasin des instrumens nécessaires à icelle (Ten books on surgery: with a catalogue of the instruments required for it)

1573: Ambroise Paré was widowed and remarried three months later, on 18 January 1574, at the age of 63, to Jacqueline Rousselet (19), daughter of the chevaucheur des écuries du roi (king's stableman). He had six children from his second marriage.

20 December 1590: He died in Paris on, shortly after the siege of Paris was lifted by King Henry IV (known for his ‘Paris is well worth a mass’).

Experience, Not Authorities

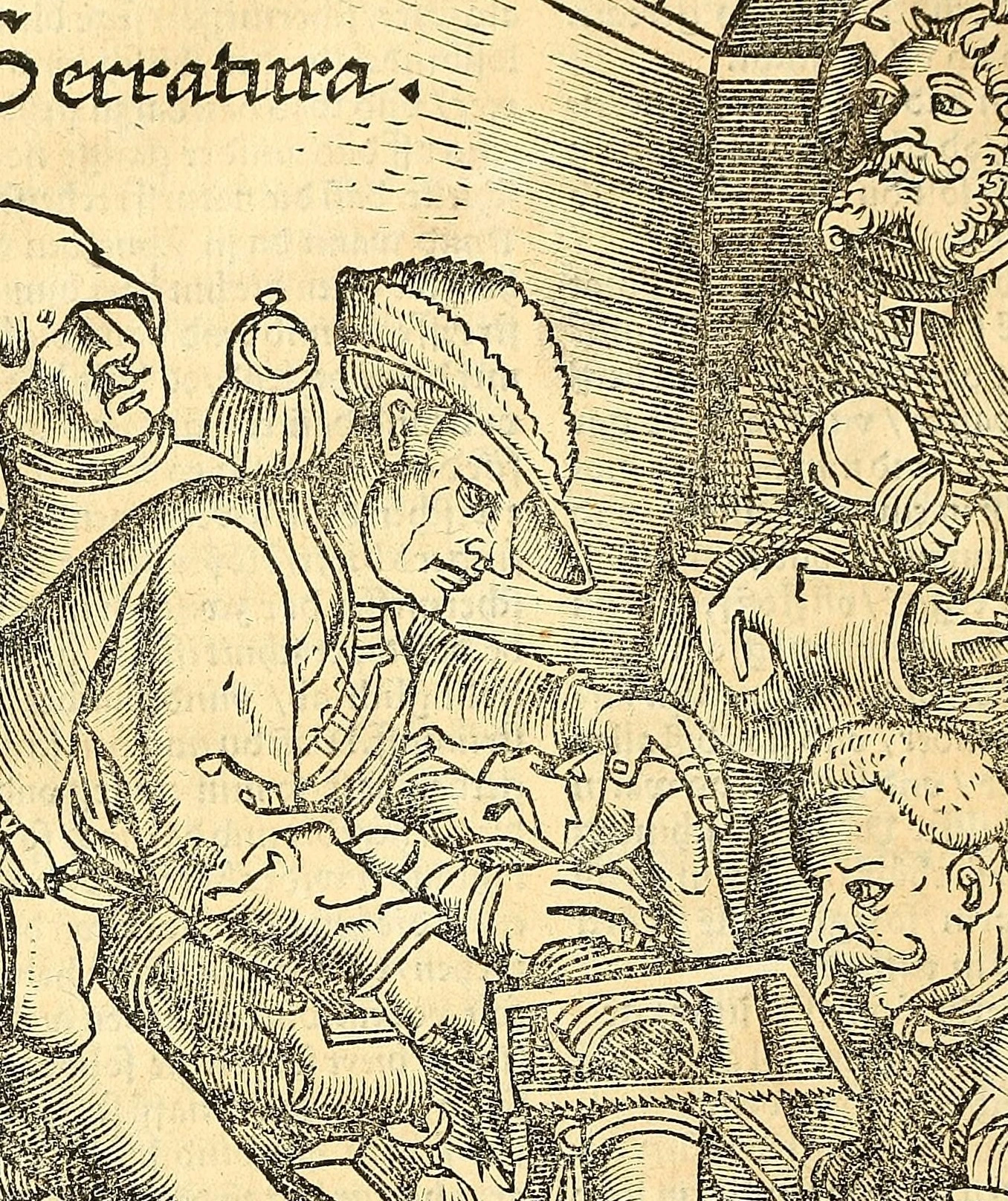

The siege of Turin in 1537 was the first defining moment in the life of the young Paré, the "Own evidence above all else" moment.

Firearms had been in use for about two centuries, but gunshot wounds were still not well understood. At that time, there were two generally accepted approaches to their treatment. Many authorities believed that gunpowder poisoned the wound. To neutralise the effect of the ‘poison,’ the accepted standard was to cauterise the wound with red-hot iron and pour boiling elderberry oil over and in it. This view was held, in particular, by Giovanni da Vigo (1450–1525), an Italian surgeon and one of the main proponents of the idea of the ‘poison’ in gunshot wounds. In his book Practica in arte chirurgica copiosa (1514), he directly stated that gunpowder poisoned wounds and suggested pouring boiling oil, turpentine, and wine alcohol on them.

Guy de Chauliac (1300–1368), a French surgeon, in his manuscript Chirurgia Magna, called for caution in the use of cauterisation and aggressive mixtures, especially in weakened patients, suggesting instead dressings, washing, and drainage. However, the printed word proved stronger than the handwritten one, and the opinion of the authoritative Da Vigo prevailed.

The scale of the battle was so great that Paré quickly ran out of elderberry oil. The young Paré then began to improvise, applying a bandage made of egg yolk, rose oil and turpentine to the wound, following a recipe by de Choliak, but one that he had not tested himself in practice. "That night I couldn't sleep... afraid that I would find those who had not been treated with boiling oil dead. I got up early to visit them. To my surprise, those who had been treated with the ointment felt almost no pain... The rest lay in fever, suffering severe pain and swelling."

This accidental experiment — one of the first controlled clinical trials — demonstrated the superiority of the soothing ointment. The antiseptic properties of turpentine (unknown at the time) promoted healing. Meanwhile, the ‘standard’ application of boiling oil caused additional damage — oil burns, pain shock, and secondary infection. Pare's book, ‘The Method of Treating Wounds...’ written in 1545 in French rather than Latin, challenged academic authorities and placed practical results above authoritative theories (La méthode de traicter les playes faictes par hacquebutes et aultres bastons à feu, et de celles qui sont faictes par flèches, dardz et semblables — The method of treating wounds caused by arquebuses and other firearms, and those made by arrows, darts, and the like).

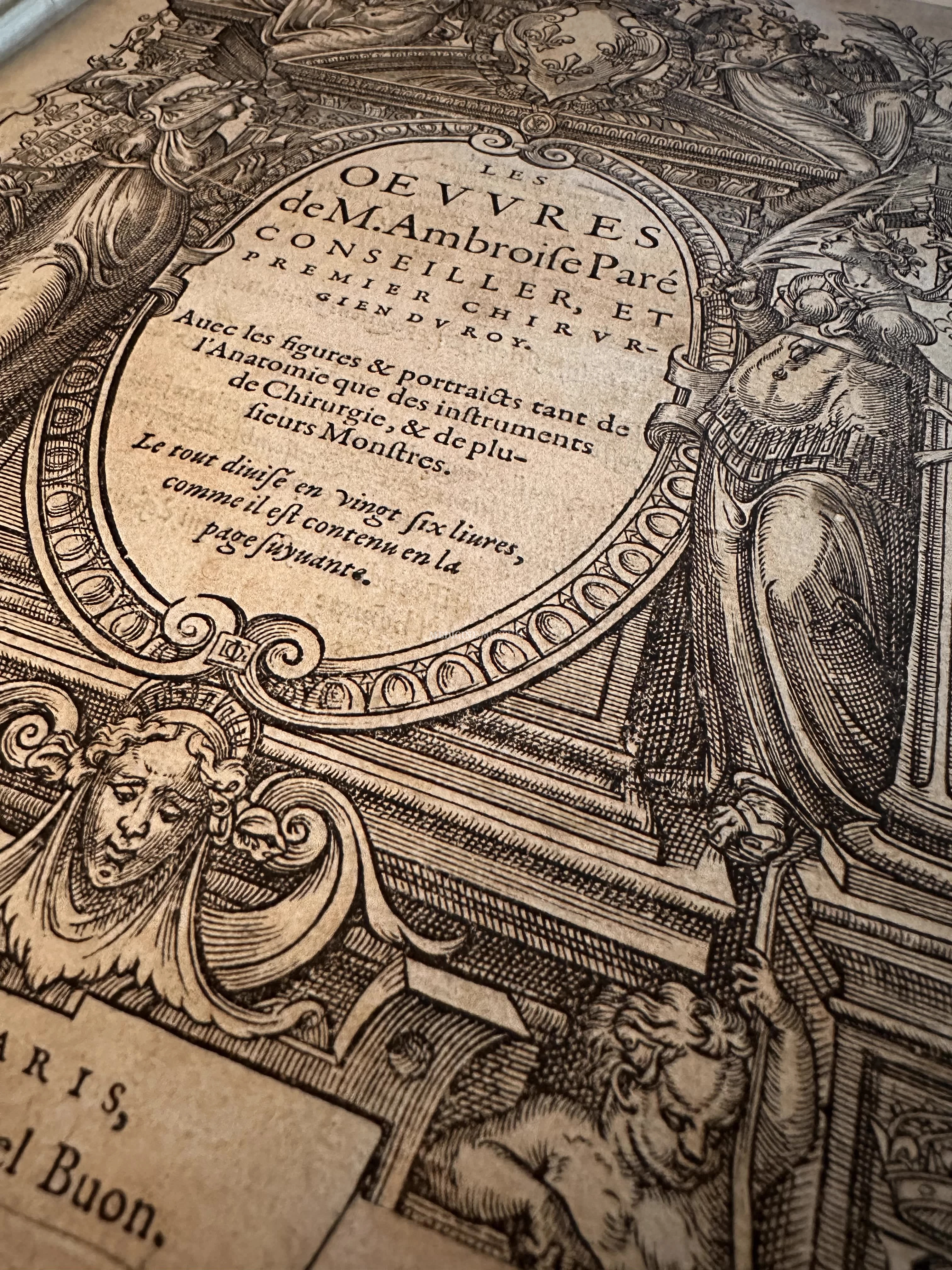

Main Publications of Ambroise Paré

1545. La Méthode de traicter les playes faictes par hacquebutes et aultres bastons à feu: & de celles qui sont faictes par fleches, dardz, & semblables: aussy des combustions specialement faictes par la pouldre à canon, composée par Ambroyse Paré, maistre Barbier, Chirurgien à Paris (The method of treating wounds caused by arquebuses and other firearms, as well as those caused by arrows, darts and similar weapons, and burns caused specifically by gunpowder, compiled by Ambroise Paré, master barber and surgeon in Paris).

The title page of the 'La Méthode de traicter les playes faictes par hacquebutes et aultres bastons à feu...' Paris, 1545. Source: The National Library of France {BnF Gallica.

An innovative treatise on the treatment of gunshot and arrow wounds, often considered the first surgical manual written in French rather than Latin (although the first comprehensive work on surgery in French was La Grande Chirurgie, a translation of the original Latin work Chirurgia Magna by Guy de Chauliac, 1363). In this book, the author advocated the use of less destructive methods of treatment with the application of a soothing ointment made from egg yolk, rose oil and turpentine, as opposed to the widespread practice of cauterisation with boiling oil, which often did more harm than good.

Full-text link: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8609572j/f11.image

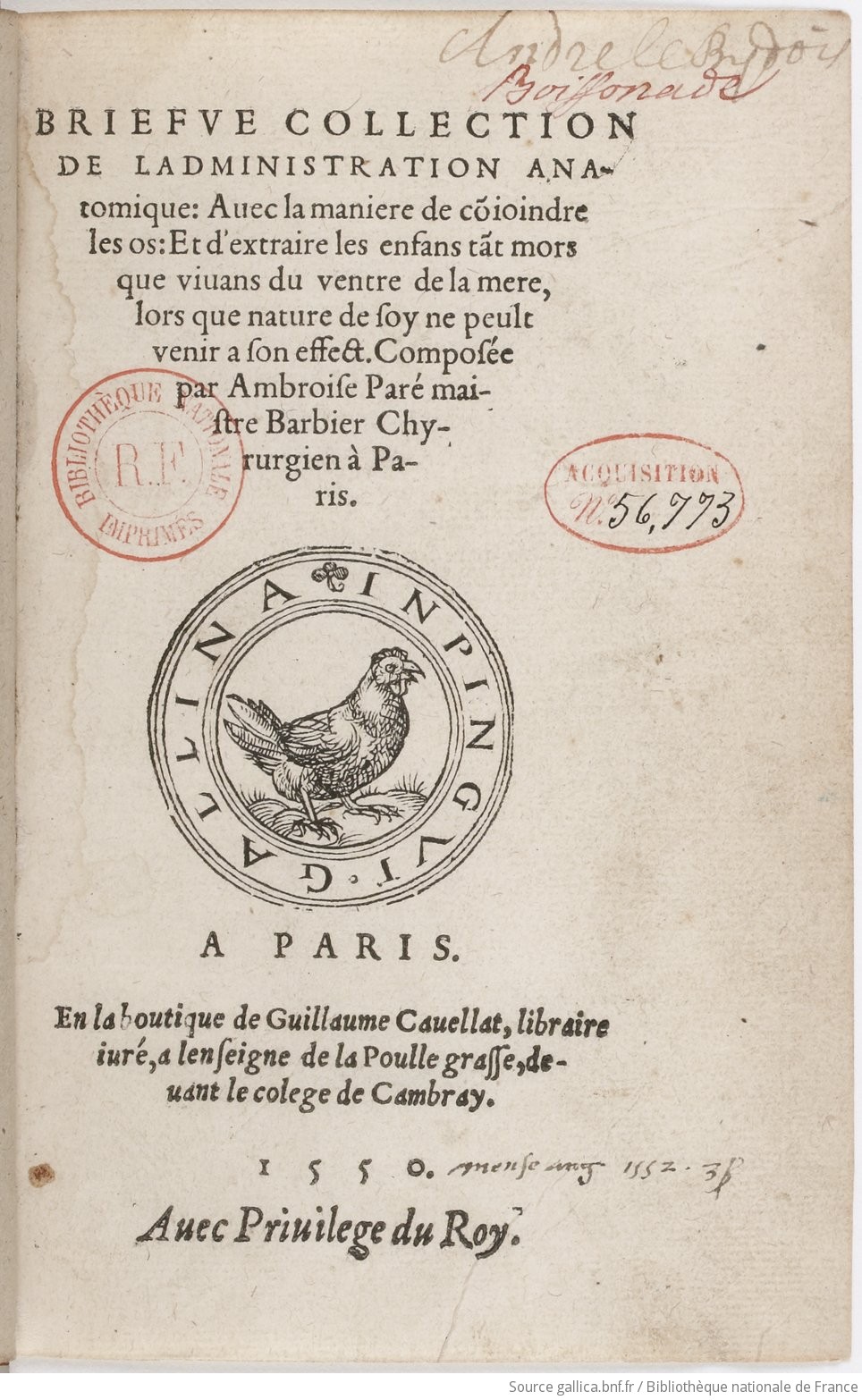

1549 (1550) – Briefve collection de l'administration anatomique : Avec la maniere de conjoindre les os : Et d'extraire les enfans tant mors que vivans du ventre de la mere, lorsque la nature de soy ne peult venir à son effect . Composée par Ambroise Paré, maistre Barbier Chyrurgien à Paris (Brief collection of anatomical administration: With instructions on how to join bones: And extract both dead and living children from the womb when nature cannot do so itself. Compiled by Ambroise Paré, master barber-surgeon in Paris). Publisher: Guillaume Cavellat, 1550

The title page of the 'Briefve collection de l'administration anatomique...' Paris, 1550. Source: The National Library of France {BnF Gallica.

The book includes detailed descriptions of anatomical administration, methods for setting bones, and techniques for extracting both deceased and living infants from the mother's womb when natural birth is not possible.

Full-Text Link: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8626181r/f7.item

1551. La Manière de traicter les playes faictes tant par hacquebutes que par flèches: et les accidentz d'icelles, comme fractures et caries des os, gangrene et mortificatoin: avec les pourtraictz des instrumentz necessaires pour leur curation: Et la methode de curer les combustions principalement faictes par la pouldre à canon. 1551, Veuve Jean de Brie, Paris

Expanded edition of his 1545 work, adding complications, illustrations of instruments, and fracture management

A passionate writer and wise investor

In the mid-16th century in France, the “price” of a printed book depended largely on its format, whether it was sold unbound as loose sheets or bound in leather, and whether it contained engravings and the number of copies printed. The price of a small book (octavo), such as Paré's field notes, was around 1–3 livres tournois. A large folio with illustrations cost 20 livres or more. The daily wage of a skilled craftsman like a barber-surgeon was about 0,5-1 livre (20 livres would be enough to buy a cow). In addition, authors rarely counted on royalties from the publisher — on the contrary, they had to cover the printing costs, while the lion's share of the profits went to the publisher if the book was successful. For the young barber-surgeon Ambroise Paré, publication was primarily a way to establish a reputation, win royal respect and academic favor, and attract wealthier clients. History showed that the risky investment of several months' earnings paid off handsomely. Later, having become the personal surgeon to four kings, he no longer suffered from a lack of funds.