L'inconnue de la Seine – a Prototype for Resusci Anne

The lives and achievements of many historically important physicians over time are covered with legends, rumours and non-existent facts. Such was the case with Hippocrates, Galen, Avicenna, Paré. As their biographies, outstanding deeds and discoveries are retold, these stories are enriched with more and more ‘facts’ and details.

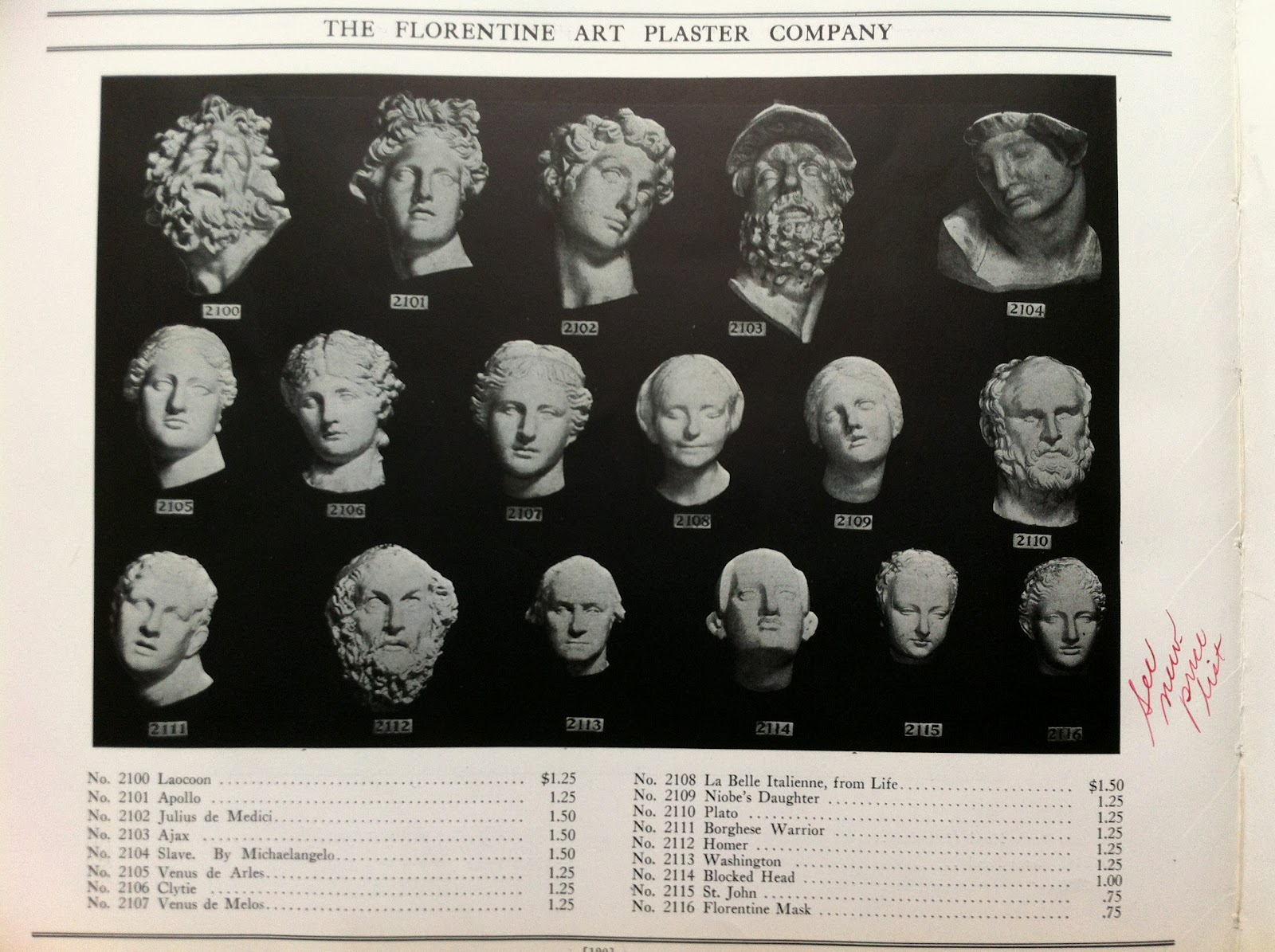

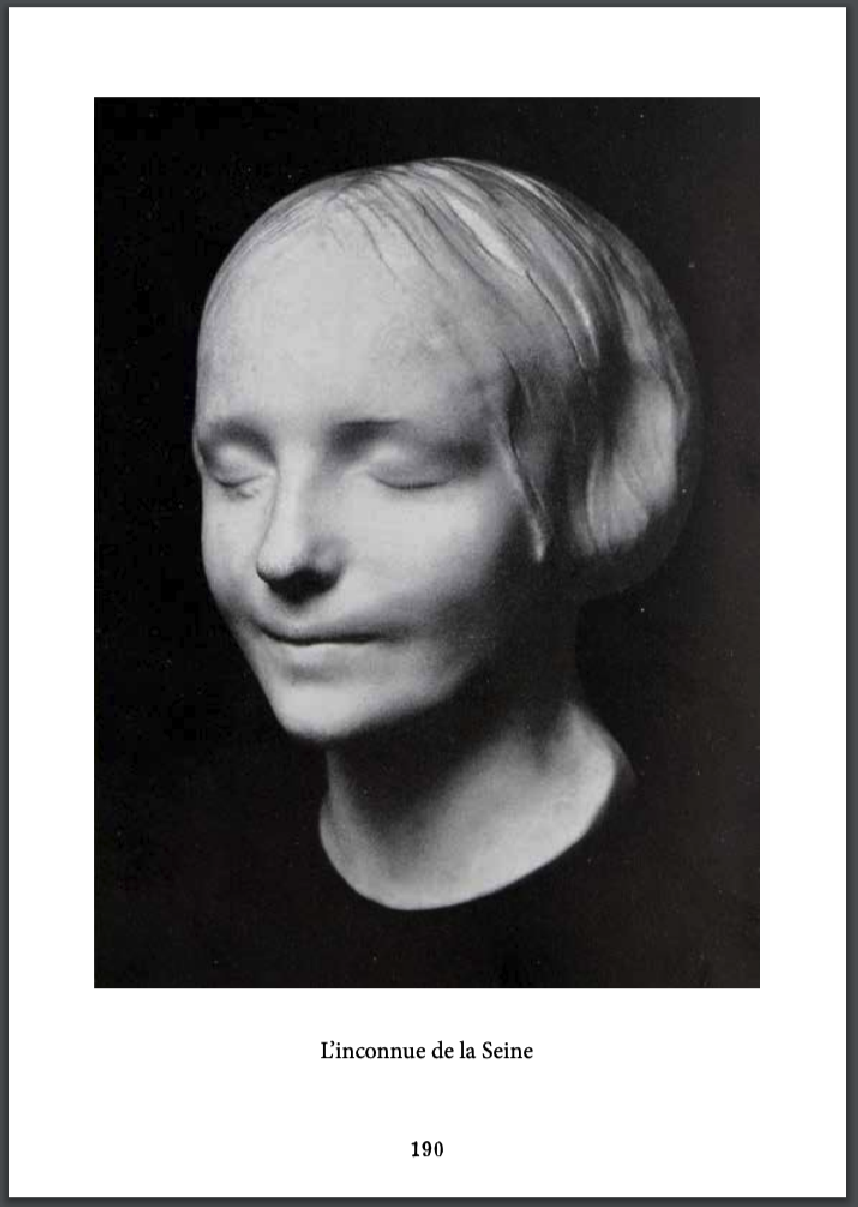

And sometimes such transformations occur with an unknown or even fictional hero, when a non-existent character gradually acquires new features, details and just variants of biography, becoming more and more tangible, real. One of such figures in the history of medicine is the plaster mask ‘L'inconnue de la Seine’ (Unknown of the Seine). In Paris, it was also called 'La Vierge inconnue du canal de l'Ourcq' or 'La Belle Noyee', and in the United States it was listed in plaster mask catalogs for sale as 'La Belle Italienne', perhaps referring to the fine examples of the Italian Renaissance for better marketing.

A page from the catalog of the Florentine Art Plaster Company, USA (1915). Here L'inconnue is juxtaposed with Apollo, Homer, and Washington. Source: felicecalchi.blogspot.com

The famous mask served as the origin for the face of the world's first and main cardiopulmonary resuscitation manikin, Resusci Anne – the trainings-doll by Norwegian company Laerdal that revolutionized the way we teach medicine.

The mask's history is worthy of further investigation, as it has been previously researched and is still a topic of ongoing study.

Story of L'inconnue de la Seine

The most known version

A pervasive account of the legend maintains that in the 1880s, a young girl's body was discovered on the embankment of Le Quai du Louvre, situated along the banks of the Seine river in Paris. No evidence of a violent death was discovered, and the girl's body was transported to La Morgue Parisienne (The Paris morgue) in accordance with standard procedures of the time for potential identification by the public.

Le Quai du Louvre (Embarkment of the Louvre), photo circa 1900. The bell towers of Notre-Dame de Paris (the Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris) can be seen far on the right, the Paris morgue was located in 1880s just behind them.

As days passed without a positive identification, the unfortunate girl was scheduled for burial. The morgue attendant, who had been daily captivated by her enigmatic beauty, commissioned the creation of a posthumous mask in order to preserve her image in perpetuity. Subsequently, the mask was reproduced in numerous casts and distributed throughout Paris, soon reaching Europe and America. It was used as a decorative element in bourgeois interiors of the 1920s and 1930s. It was given the stage name ‘L'inconnue de la Seine’ (Unknown of the Seine), becoming a romantic or even erotic symbol of the era.

The legend persists and evolves

In the future, the fate of the girl who committed suicide by throwing herself into the Seine has repeatedly attracted the attention of numerous poets, writers, and artists. A "plausible version" emerged, positing that the motivation for the act was an unhappy, unrequited love. This seems a likely explanation for a 16-year-old child to commit such a desperate, irrevocable act. From the beginning of the 20th century until the Second World War, L'inconnue de la Seine became a veritable symbol of undivided, pure, light love, inspiring people of art, as well as a fashion accessory, a must-have object of any living room.

The initial literary work to mention the mask was the 1898 story 'The Worshipper of the Image', authored by British-American poet and writer Richard La Gallienne and published in 1900. This narrative has served as the foundation for numerous retellings and further interpretations. As time passes, more and more “details and facts” of her life and the circumstances of her death come to light.

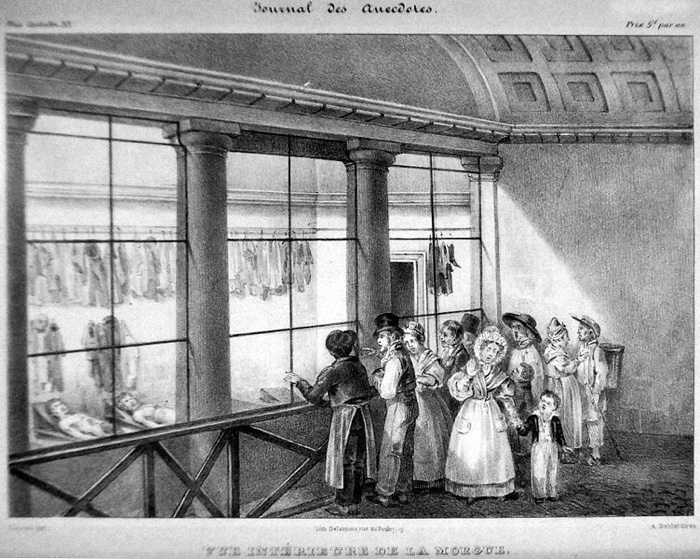

At the end of the 19th century, Paris's morgue sat perched just behind Notre Dame cathedral, on the edge of the island in the Seine, l'Ile de la Cité. Two-thirds of the corpses dealt with by the morgue would have been fished out of the Seine - suicides, accidental drownings or murders. The morgue attendants would carefully study the dead person's clothes, scars and wounds - often caused after they had hit the water, by a boat or by the hooks used to fish them out. Then the bodies would be displayed on 12 black marble slabs propped up in the morgue window for the public to view and decide whether they recognised any of them.

This macabre showcase became one of the most popular pieces of entertainment in Paris. Locals and tourists peered in at the forsaken departed souls. People of all ages, including children, would visit the famous window of the dead - Émile Zola, in his 1867 novel Thérèse Raquin, described gangs of boys, aged from 12 to 15, "who ran the length of the window, only stopping in front of the female corpses."

Interior view of the Morgue, presented at the Musée de la Préfecture de Police, Paris. One can see the clothes and other personal things hanging above the corps. Credit: Wikipedia

The undeniable facts about the L'inconnue mask

- The mask of a young woman's face, calm and peaceful, even smiling

- The mask is made of plaster

- There are many copies and replicas of the mask in museums and private collections around the world. The masks are not identical. Some of them are over 100 years old and notable examples include:

- Museum for Sepulchral Culture in Kassel, Germany;

- Musée des Beaux-Arts, Quimper, France;

- Museum of the Order of St. John, London, UK. - There is no documentary evidence to support the well-known legend of a postmortem mask removed from the face of an unknown drowned woman in the Paris morgue. There are no police protocols, notes in the morgue books, etc.

- Majority of the modern descriptions of the morgue, its premises, and the procedure for identifying unknown corps is based on a text in the book 'Illustrations de Paris à travers les âges' by Fédor Hoffbauer, published 1875-1882, which describes a morgue demolished in 1860, a quarter of a century before the girl's alleged date of death. However, it can be the

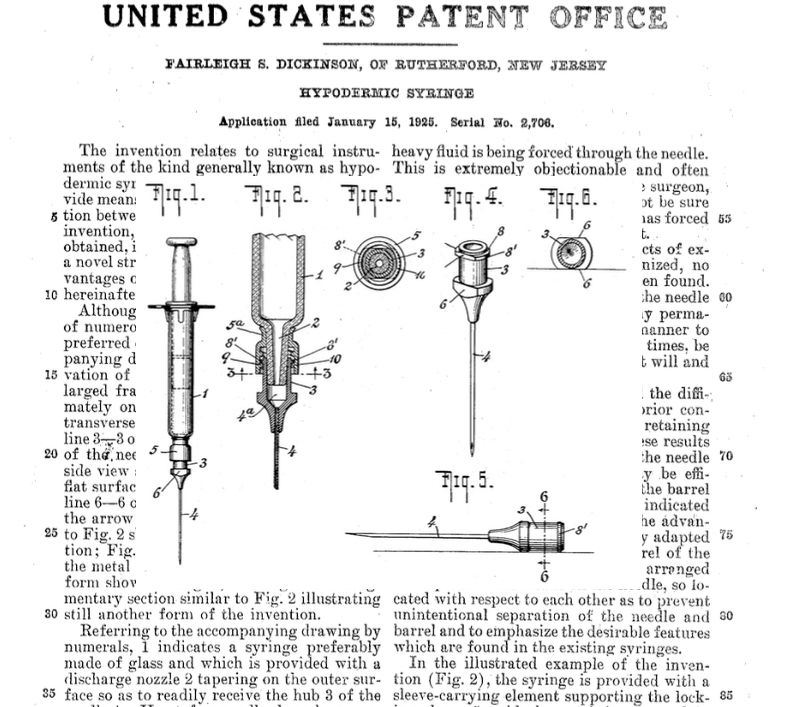

- The first documented reference to this mask is found in the book entitled 'Cours de dessin. 1re partie, Modèles d'après la Bosse'. Paris, 1867 by Charles Brague and Jean-Léon Gérôme (Drawing course. Part 1, Models after La Bosse).

- The first literary reference to this mask was the story ‘The Worshipper of the Image,’ written by British writer Richard La Gallienne in 1898 and published in 1900.

- Another image of this mask that became popular in the 1930's was the photo in the book dedicated to Ernst Benkard's collection of 123 posthumous masks, 'Das ewige Antlitz' (Frankfurt, 1926), published in 1929 in English under the title 'Undying Faces'.

What we do not know for sure

- The mask and its cast was probably made in France or Germany.

- Judging by the facial features and skin structure – the model was very young, most likely she is about 16-19 years old, however the age definition is approximate and speculative.

- This was most likely a postmortem mask, but still not for sure, and if it was – the cause of death is unknown.

And, by the way, if you compare the masks from the museums, you will definitely see the difference. They are not the same – some versions are more smooth, "artistic". One can see the gradual deterioration of details, the disappearance of eyelashes first from the left eye (on the right eye they will be considered as the remains of silt and sand on the face of the unfortunate drowned maiden), then the eyelashes disappear from the right eye as well, the bulges from the eyeballs on the eyelids will be smoothed out, and finally the neck will be vanished from the mask.

The plate 53 in the 'Cours de Dessin' (1867) by Charles Bargue illustrates the most ancient image of the mask. Source: Internet Archive

The mask exhibited at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Quimper, France; private collection, copyright Frédéric Harster

The page fro the book "Das ewige Antlitz: Eine Sammlung von Totenmasken" depicting the collection of death masks of Ernst Benkard (Frankfurt, 1927).

One of the variants of the mask. More artistic but no flaws, no peculiarities, no neck... Source: Museum für Sepulkralkultur, nat.museum-digital.de

Influence for the art and literature

The image of an unknown girl drowned in the Seine inspired many artists to create their works - short stories, novels, poems, plays, one movie and even a ballet were created using this image with several samples listed bellow.

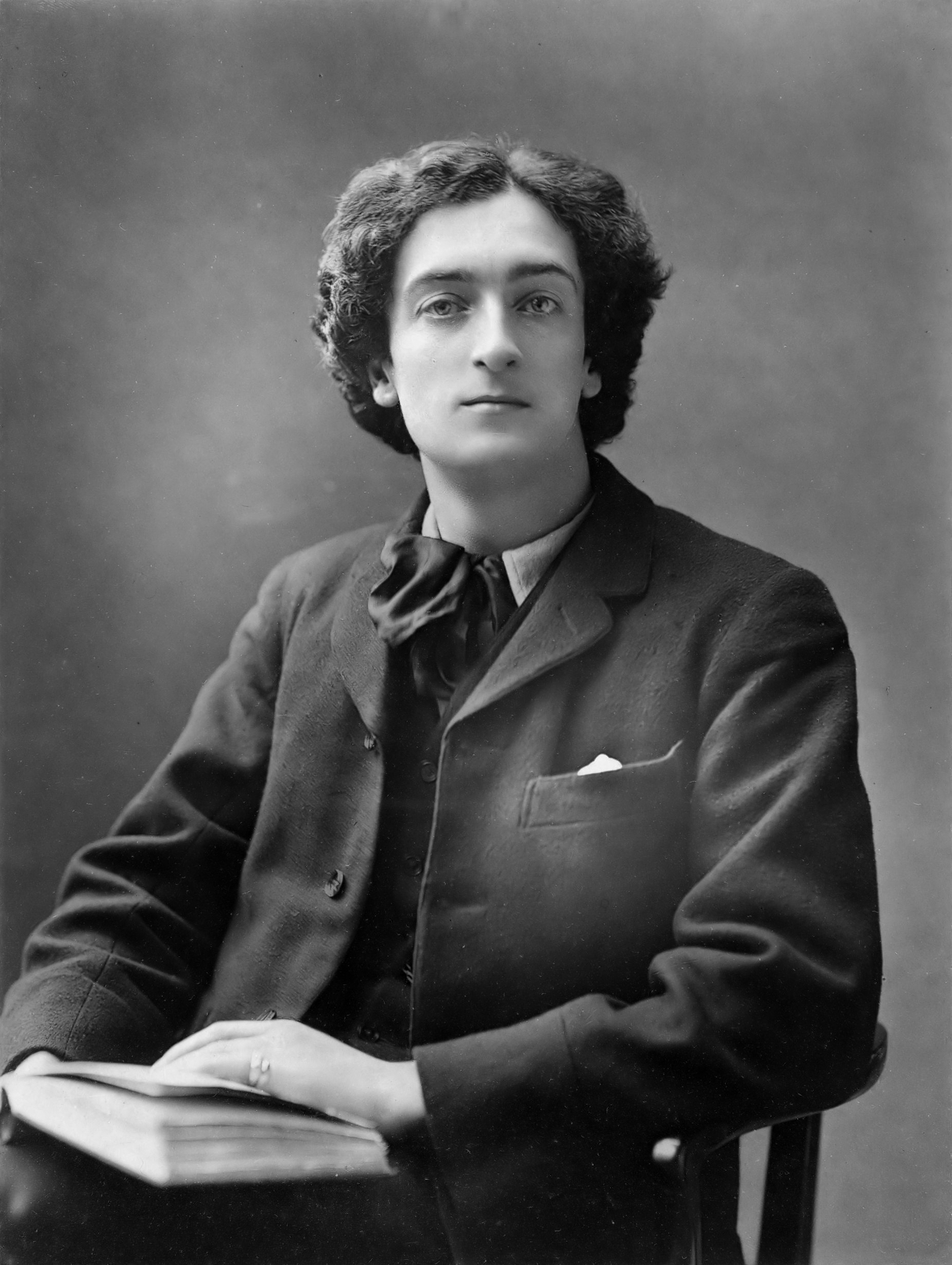

1898. Richard La Gallienne

Richard Le Gallienne (1866–1947), British-born American critic, essayist, and poet. Source: Wikimedia.

'The Worshipper of the Image', written in 1898 by British-American writer Richard La Gallienne (1866–1947) and published in 1900 was one of the first literary references to this legend. Here are some quotes from the story:

"At one end of it, on a small vacant space of wall, hung a cast, apparently the death-mask of a woman, by which the eye was immediately attracted with something of a shock and held by a curious fascination. The face was smiling, a smile of great peace, and also of a strange cunning. One other characteristic it had: the woman looked as though at any moment she would suddenly open her eyes, and if you turned away from her and looked again, she seemed to be smiling to herself because she had opened them that moment behind your back, and just closed them again in time.

It was a face that never changed and yet was always changing.

She looked doubly strange in the evening light, and her smile softened and deepened as the shadows gathered in the room.

Antony came and stood in front of her.

"Silencieux," he whispered, "I love you, Silencieux. Smiling Silence, I love you."

***

“Beatrice gave the mask back to Antony, with a little shiver.

"It is very wonderful, very strange, but she makes me frightened. What was the story the man told you, Antony?"

"No doubt it was all nonsense," Antony replied, "but he said that it was the death-mask of an unknown girl found drowned in the Seine."

"Drowned in the Seine!" exclaimed Beatrice, growing almost as white as the image.

"Yes! and he said too that the story went that the sculptor who moulded it had fallen so in love with the dead girl, that he had gone mad and drowned himself in the Seine also."

"Can it be true, Antony?"

"I hope so, for it is so beautiful,—and nothing is really beautiful till it has come true."

"But the pain, the pity of it—Antony."

"That is a part of the beauty, surely—the very essence of its beauty—"

"Beauty! beauty! O Antony, that is always your cry. I can only think of the terror, the human anguish. Poor girl—" and she turned again to the image as it lay upon the table,—"see how the hair lies moulded round her ears with the water, and how her eyelashes stick to her cheek—Poor girl."

1910. Rainer Maria Rilke

The famous Austrian poet and novelist Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) brought a copy of L'inconnue de la Seine back to Berlin from Paris in 1905. Rilke probably bought it from the atelier of Michele Lorenzi, a 'moueur' – a specialist in plasterwork, stucco and posthumous masks. The Internet often claims that Lorenzi was that one who created the posthumous mask. However, the Italian master came to the French capital from Tuscany and opened his store in Paris on the Rue Racine in 1871, four years after the publication of the 'Course in Drawing'. Nevertheless, Rilke worked in Paris in 1905 on a biography of the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin. His impressions of that period were reflected in 1910 in his famous novel 'Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge' ('The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge'), where he wrote:

“Der Mouleur, an dem ich jeden Tag vorüberkomme, hat zwei Masken neben seiner Tür ausgehängt. Das Gesicht der jungen Ertränkten, das man in der Morgue abnahm, weil es schön war, weil es lächelte, weil es so täuschend lächelte, als es wüßte.”

"The mouleur, whose shop I pass every day, has hung two plaster masks beside his door. [One is] the face of the young drowned woman, which they took a cast of in the morgue, because it was beautiful, because it smiled, because it smiled so deceptively, as if it knew.").

By the way, the atelier Lorenzi still exists in Paris today, though it is no longer located on Rue Racine, but in another part of the city (atelierlorenzi.com).

1931. Jules Supervielle

The poet Jules Supervielle (1884-1960), born in Montevideo to French parents, also owned a mask and wrote in 1931 a rather fantastic story 'L'Inconnue de la Seine' from the viewpoint of the 19-year-old drowned woman as she was moved by the Seine's current towards the sea:

"Elle allait sans savoir que sur son visage brillait un sourire tremblant mais plus résistant qu'un sourire de vivante, toujours à la merci de n'importe quoi."

"She traveled not knowing that on her face shone a trembling smile, far more unremitting than the smile of the living, which is always at the mercy of whatever may come."

1934. Vladimir Nabokov

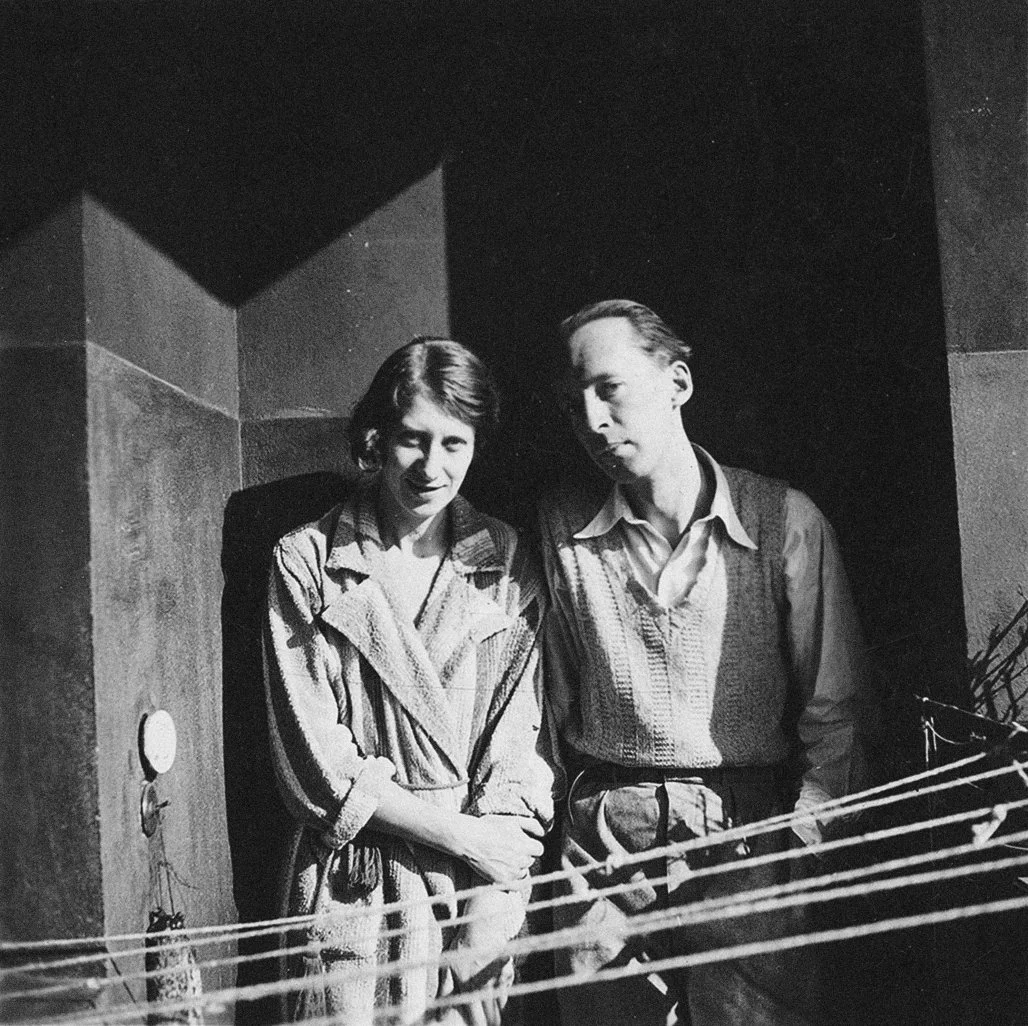

Vladimir Nabokov and his wife Vera in Berlin, 1930s. Notice hairstyle of Vera, that bob-caré was in vogue in Europe in the 30's, but after all it's the same hairstyle as the plaster girl. Source: qalam.global

The famous Russian writer and poet Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977), known to the world primarily for his novel 'Lolita', lived between the two world wars in Berlin. Nabokov, reflecting on the short tragic fate of the girl, wrote a poem in 1934, which was published untitled on June 28, 1934 in the Russian-language Parisian émigré newspaper 'Последние новости' (Last news). In subsequent publications the poem was given the title L'inconnue de la Seine. The poet Jules Supervielle, whose work is quoted above, was a friend of Vladimir Nabokov, and the plaster mask was as popular in Berlin as it was in Paris. The verse was written in Russian language in Berlin, and was later to be included as a poetic component in the novel 'Дар' (The Gift), published in 1937 – hence the dedication 'From F. G.-Ch.' after the initials of the novel's hero.

L'Inconnue de la Seine

(English translation follows)

Торопя этой жизни развязку,

не любя на земле ничего,

все гляжу я на белую маску

неживого лица твоего.

В без конца замирающих струнах

слышу голос твоей красоты.

В бледных толпах утопленниц юных

всех бледней и пленительней ты.

Ты со мною хоть в звуках помешкай,

жребий твой был на счастие скуп,

так ответь же посмертной усмешкой

очарованных гипсовых губ.

Неподвижны и выпуклы веки,

густо слиплись ресницы. Ответь,

неужели навеки, навеки?

А ведь как ты умела глядеть!

Плечи худенькие, молодые,

черный крест шерстяного платка,

фонари, ветер, тучи ночные,

в темных яблоках злая река.

Кто он был, умоляю, поведай,

соблазнитель таинственный твой?

Кудреватый племянник соседа -

пестрый галстучек, зуб золотой?

Или звездных небес завсегдатай,

друг бутылки, костей и кия,

вот такой же гуляка проклятый,

прогоревший мечтатель, как я?

И теперь, сотрясаясь всем телом,

он, как я, на кровати сидит

в черном мире, давно опустелом,

и на белую маску глядит.

1934, Берлин

L'Inconnue de la Seine

(English translation by Maxim Gorshkov, 2024, Stuttgart)

Urging towards my ultimate task,

No love on this Earth, in that space.

I keep starring at white plaster mask

At your lifeless and calm tender face.

In the sounds of strings screaming, dying

I can hear the voice of your call

In the crowds of girls drowning, crying

You‘re the palest and dazzling of all.

You shall stir with me in those sounds

Your unfortunate fate was not blessed,

I'm yearning to break plaster bounds

Of the smile that made me obsessed

No blinks, no motions in eyelids,

Lashes sticked. I beg your replies.

Is it really forever? You dared

Shatter life in your beautiful eyes!

Tiny, young, diminutive shoulders,

Woolen shawl crossed to capture her fever.

Wind, lanterns, stormy clouds and boulders

On the dark way to ominous river.

Who was he, I plead you to tell me,

That mysterious dude that seduced.

Was he chatty and curly-locks nephew?

Fancy tie, cheeky grin, golden tooth?

Was he regular of starry heavens?

Friend of bottle, of bones and cue?

And his scoundrel’s life was God damned,

Worthless dreams were not meant to come true.

And tonight, shaking his whole body,

On the bed, just like me, in the dusk,

In this black world, alone and shoddy,

Finding her in the white, plaster mask.

Vladimir Nabokov, 1934, Berlin

Translation: Maxim Gorshkov, 2024, Stuttgart

1956. Albert Camus

The French writer and philosopher Albert Camus (1913–1960) put into the mouth of the hero of his 1956 novel 'La Chute' ('The Fall'), the self-proclaimed penitent judge Jean-Baptiste Clamence, a comparison of the mysterious smile of L'inconnue de la Seine, with the famous enigmatic facial expression of another fine art work, the Gioconda by Italian genius Leonardo Da Vinci:

“Have you noticed that there are only two luminous smiles in the history of art: the smile of the Mona Lisa and that of the Inconnue de la Seine? Not so much, perhaps, as to compare them; but one and the other have the same slightly frozen, slightly forced melancholy, the same faintly bitter love of fate, the same resigned impatience.”

The trace in medicine

Åsmund Laerdal (1913–1981), Norwegian manufacturer of children's books, plastic dolls and toy cars, in the 1960s was captivated by the news about innovative way to save drowning people by performing 'mouth-to-mouth' respiration. He came up with the idea of creating a life-size doll to practice the technique, which would inspire confidence and empathy in those learning the technique. Laerdal knew that in the culture of the 1960s, the idea of touching a man's lips with your mouth might not be popular with many people. He needed a female face. It was in this context that L'Inconnue de la Seine seemed like the perfect choice. The mask's ethereal beauty and calm expression belied the grim reality of cardiac arrest, but at the same time evoked a powerful emotional response.

Here is how, in Dr. Gordon's words, Laerdal recounted in New-York in 1960 his decision: "In addition to the original criteria established for the training manikin, he added that it should be life-size, realistic in appearance, and aesthetically appealing. As the manikin evolved, he struggled to find a face that truly satisfied him. One day, while visiting his in-laws, he noticed a death mask of a young girl on the wall. He was immediately captivated by her mystical beauty. It struck him that this mask, taken from a person who died in her youth, would be ideal for teaching people how to save lives." (quoted from “A Death Mask to Save Lives (The Story of Resusci-Anne)” by Archer S. Gordon, MD, PhD).

By using L'Inconnue as the face of Anatomic Anne and Resusci Anne, Asmund Laerdal achieved several goals. First, he created a realistic and believable figure associated with an accident, with drowning, with death, and capable of evoking compassion and a desire to help. Secondly, the serene expression of the mask helped to relieve the anxiety often associated with CPR training. And thirdly, it transformed a tragic story into a symbol of hope and survival.

The decision to use L'Inconnue de la Seine as the face of Resusci Anne was a stroke of genius. It transformed a simple training tool into an iconic image recognized the world over. Millions of people become resuscitation specialists, and Resusci Anne is crowned as 'The Most Kissed Woman in the World' paying tribute to her predecessor and making up for her unfortunate fate. The mask, once an enigmatic relic of the Parisian tragedy, became a beacon of hope, inspiring countless people to learn cardiac pulmonary resuscitation and to save lives.

One of the first models for the mouth-to-mouth respiration and chest compressions training, 'Anatomic Anne' made by the firm Laerdal in 1960s. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov

Epilogue

We know nothing about L'inconnue de la Seine except a few facts mentioned above. All other "details” about this mask are nothing more than speculations based on literary fiction and fantasy. But humans cannot be satisfied with mere facts - people need intrigue, legend, fairy tale. Like a story about L'inconnue de la Seine...