Anatomy wax model 'made in Italy'

Wax anatomical models designed to train physicians and educate the public were once innovative educational teaching aids. Some world-class museums including La Specola in Pisa, Josephinum in Vienna, Palazzo Poggi in Bologna, Science Museum in London, Semmelweis Museum in Budapest, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris are proud of their collections. This amazing craft, combining art and science, anatomy and chemistry, practical skill and theoretical knowledge, which stood at the forefront of innovation in the 17th and 18th centuries, originated and flourished in Northern Italy.

First wax anatomy models

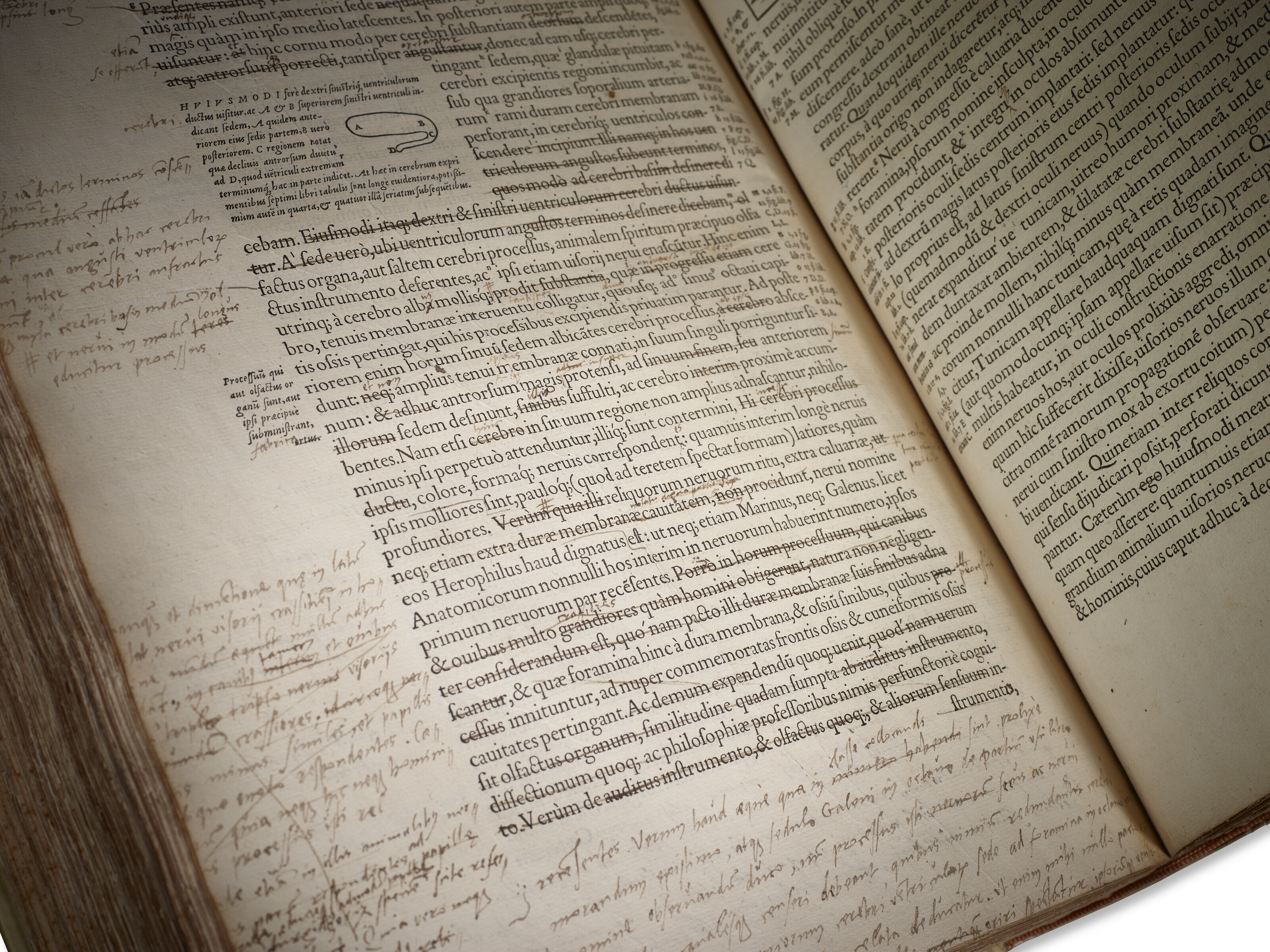

The study of anatomy in Medieval and Renaissance had great challenges. Even after the dissections of the human cadavers were formally allowed, the unresolved problems of the source of cadavers and the conservation of the corps and anatomical specimens complicated the learning process.

Previously, teaching aids had been made of different materials including painted terracotta (fired clay). However, clay was too coarse material to represent small structures such as delicate blood vessels and nerves. These problems could be solved by coloured wax sculpture, a technique that had been known for quite some time in Italy. For instance in Florence, from the 13th to the 18th century, there was a whole industry of workshops that produced wax statues of both religious content and sculptures of real people. Florentine and foreign nobles commissioned coloured wax life-size figures (bóti) depicting themselves, which were dressed in their clothes and then offered to the church as an ‘ex-voto' – act of devotion.

It is worth noting that votive wax offerings were banned in the late 18th century by the Grand Duce Peter Leopold, who played important role in the development of wax anatomical teaching aids (see below). Portrait wax sculpture was further developed in France and England and many of us are familiar with it from the Madame Tussauds Museum, first opened in London in 1835 by the French sculptor Marie Tussauds (1761-1850) and subsequently opened branches in many countries on four continents.

The first wax anatomy sculpture considered to be Lo Scorticato (Ital. – exfoliated, skinned), a small skinless male figure in an expressive pose demonstrating superficial muscles of a man (ca. 1597). This statue is an artwork by Ludovico Cardi called Cigoli (1559-1613), and is on exhibit today in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. The figure presents external musculature layers, while having dimensions smaller than life-size – so, it was created by a sculptor, rather than formed by the technique of a cast from an actual human cadaver, as was often practiced later for wax anatomical models.

A small skinless figure of a man Lo Scorticato (ca. 1597) is a first wax anatomy sculpture. This statue is an artwork by Ludovico Cardi (Cigoli), presented today in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (Photo credit).

Gaetano Giulio Zumbo

The next important step was made by a talented abbot Gaetano Giulio Zumbo (1656-1701), a native of Sicily. Zumbo worked from 1691 until 1694 for the Grand Duce Cosimo III de Medici, commissioned for him several works (though rather not anatomical, but more artistic). Most of his works were devoted to religious themes, however during his short visit to the Bologna in 1694 his artistic interests shifted toward anatomy.

In 1695, Zumbo relocated to Genoa, where he began collaborating as an anatomical wax modeller with French anatomist and surgeon Guillaume Desnoues. This partnership is often regarded as the foundation of anatomical wax modeling. However, their collaboration ended prematurely due to a heated dispute over credit for the wax models. In many occasions where art services to science, we will continue to see similar confrontations on about who is primary, the sculptor or the anatomist, the creator or the administrator.

Desnues used dry fixed anatomical preparations in his lectures. This process required exceptional skill in the dissection of cadaveric tissues, as well as the use of sophisticated technical procedures and chemically selected tissue fixatives to ensure the long-term preservation of the specimens. The work was extremely laborious and time-consuming and did not always produce correct results of satisfactory quality and durability. French surgeon developed his own unique method of preservation, which consisted of pre-filling the jars with warm, dry air and introducing coloured substances into them. The specimens were then prepared using classical anatomical dissection techniques.

From these carefully prepared specimens, Zumbo was able to make excellent quality casts from which he created wax sculptures. Even in his famous Florentine miniatures, the ceraiolo showed a particular interest in the signs of post-mortem decomposition of the corpse, which he carefully reproduced on his models after finding them in the original specimens. His scientific adviser did not like this and, under pressure from Desnues' remarks, the sculptor removed these elements from the head.

By 1700, Zumbo had moved to Marseilles, and later exhibited an anatomical 'Head' at the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris on May 25, 1701. This was extremely realistic model with the skin removed, with a sawed skull and one brain hemisphere has been removed, exposing the inside of the skull. Demonstration had tremendous success, the model was immediately purchased for the Academy by the King Louis XIV, and the sculptor was granted the 'royal privilege' for the wax anatomical sculptures manufacturing.

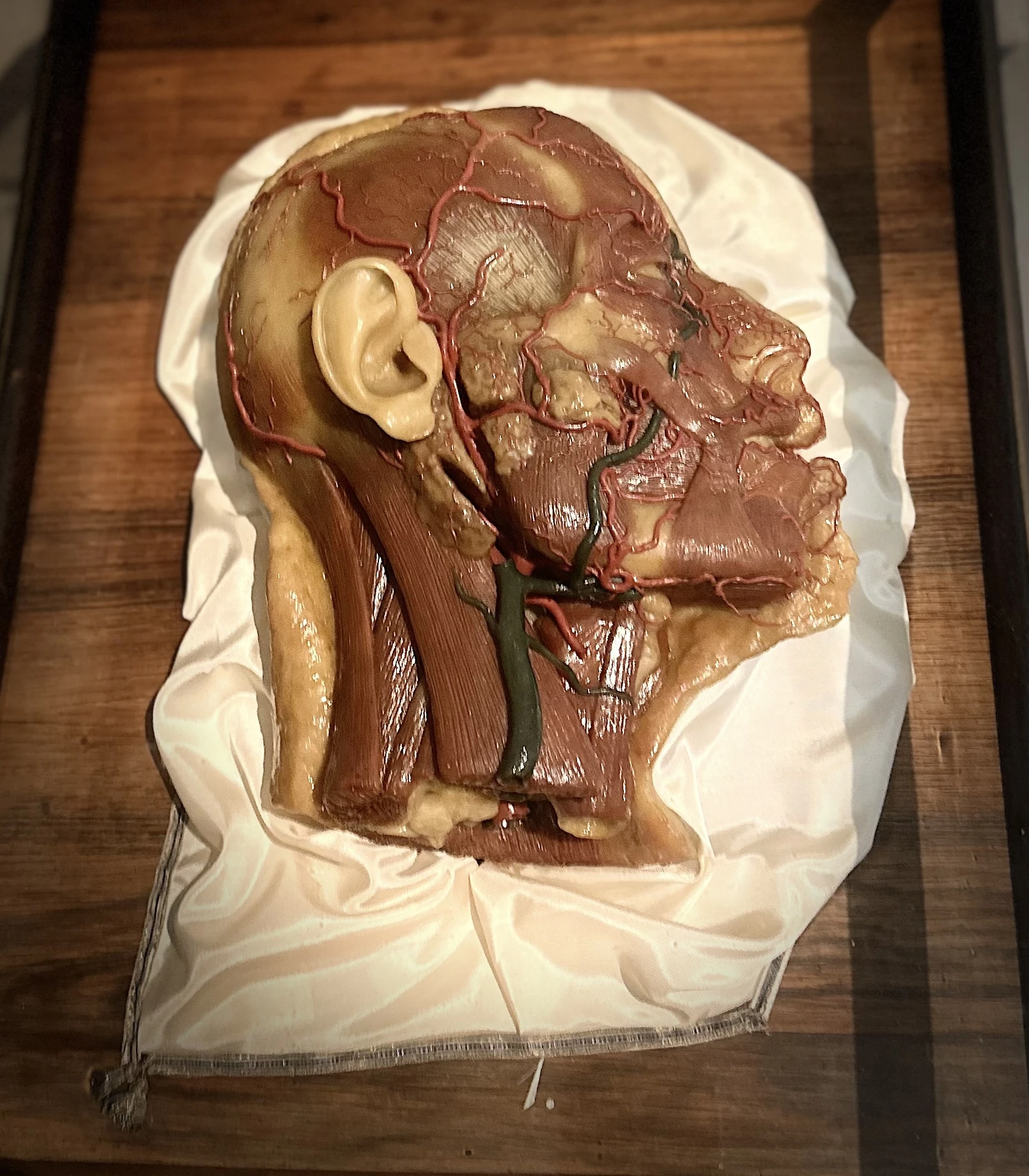

Today, two copies of Zumbo's head models survive – one in La Specola in Florence, the other in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. The head in La Specola was created by applying many layers of coloured wax to the real skull of a young man. A characteristic feature of Zumbo's style was the preservation of the natural colours of death, showing the decay of cadaveric tissue: the greenish color of the skin, the half-closed eyelids, the drops of dried blood coming out of the nose and in the corner of the half-open mouth with barely visible teeth inside. The skin on the left side of the head is scalped, exposing the facial musculature, fascia, blood vessels, parotid, submandibular and thyroid glands. The cranial vault is sawed off and along with the left brain hemisphere extracted from the cranium and placed aside. The right hemisphere is in its natural anatomical position inside. Researchers have not yet reached a consensus on whether this head was created back in Florence or was the result of a meeting and collaboration between Zumbo and Denuez. In any case, the dating on the plaque near the exhibit places it in the second period. This one, the most ancient head, exhibited in Florence is considered the first known anatomic wax model designed for scientific purposes [Puccetti ML et al., 1995].

Gaetano Zumbo, the Head, wax anatomy model, 1700. Museum of Natural History, La Specola, Florence, Italy. Credit: wikipedia.

The second anatomical model that has survived to this day was made in Paris in 1701, and is presented now in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. The 'Head of an old man' is fromed entirely in wax and has no real skull inside – all parts are made of wax. The right side of the skull is covered with skin, as is the right side of the face and neck. The tissues and organs underlying the facial muscles are shown with the exception of the removed masseter muscle. The left side with skin is a portrait of an old man with finely wrinkled skin.

Wax anatomy in Bologna

Bologna occupies a crucial place in the history of anatomical research and wax modelling. The city, home to the world's oldest University of Bologna, became the centre of medical education during the Renaissance and Enlightenment. The establishment of the Istituto delle Scienze (Institute of Sciences) in Bologna in 1714 was an important turning point. The anatomical theatre of the Institute became a centre of teaching and research, attracting outstanding anatomists and artists. Ercole Lelli, sculptor and anatomist, was a key figure in the Bolognese tradition of wax modelling. Lelli created realistic wax figures that meticulously reproduced the muscles, organs and structures of the human body, which were widely used in teaching. They allowed students to study the human body in detail without relying on dissection alone. These models provided a three-dimensional view of anatomy, enhancing medical education in a way that books and two-dimensional illustrations could not.

Anna Morandi Manzolini, one of the most prominent figures in the Bolognese tradition of wax modelling, further advanced the field. A self-taught anatomist and sculptor, Morandi became famous for her ability to create highly detailed anatomical models. Her work was not merely artistic; it was the result of careful scientific study. Morandi's models often demonstrated the nervous and vascular systems with remarkable accuracy, and her contributions earned her recognition among Europe's scientific elite.

Morandi was also a rare example of a woman who excelled in a field that was dominated by men in the eighteenth century. Her success was a testament to her extraordinary talent and intellect, as well as to Bologna's progressive attitude towards education and the sciences.

Peter Leopold, the Grand Duke of Tuscany

The Florentine school of anatomy wax modelling was than influenced from the Bolognese school, whose superior models inspired polymath Felice Fontana (1730–1805) and surgeon Giuseppe Galletti (1738-1819). Galetti was appointed in 1759 as a Maestro sostituto in Chirurgia (Substitute Teacher of Surgery) at the maternity ward of the Arcispedale di Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. He used terracotta, wax models and even obstetrical machines (training simulators) to educate surgeons and midwives. Recognizing the obvious advantages of ceroplasty (wax modelling) as visual aids, he hired a sculptor Giuseppe Ferrini to create some obstetric and wax anatomical models.

In 1766, the physicist, anatomist and naturalist Felice Fontana was appointed professor of physics at the University of Pisa and superwised in Florence the large collection of natural curiosities such as fossils, animals, minerals and exotic plants acquired by several Medici generations. By the Decree of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Peter Leopold, the Real Gabinetto di fisica e di storia naturale di Firenzi (Royal Cabinet of Physics and Natural History of the Florence) was established on 21 February 1775 and it's director was assigned Fontana. He asked Duke Leopold to finance a wax workshop to create an exhibition of anatomy models similar to those in Bologna for the future museum of natural history. The sovereign was initially opposed to the idea, but was later persuaded by his court scientist, who argued that a complete collection of anatomical models would greatly expand or even replace the dissection of cadavers. Leopold was an intelligent person and open to the problems of science. But even as scientifically progressive as he was, he disapproved of dissecting human cadavers, regardless of the purpose of the act. Thus Fontana's arguments fell on prepared ground and he took advantage of this aversion of the Duke by explaining to him that once all human anatomy was done in coloured wax, there would no longer be a need to dissect cadavers for research purposes. So, the ceroplasty workshop became part of the museum, which exhibited a Medici collection of minerals and other rarities including scientific tools of Galileo and Toricelli.

pinting 1775.jpg)

Felice Fontanaю by Clementino Vannetti (1754-1795) pinting 1775

The creators of the museum aimed not so much at specialized education as at public enlightenment, and in a few years the wax collection was viewed annually by up to 20,000 people. In its inauguration in 1775, the museum consisted of 35 halls and was open from 8:00 to 13:00 for «people of the city and countryside who may enter as long as they are cleanly dressed». The order was supervised by «4 unarmed Palatine Guards who will ensure that people of the lower class, admitted to the above-mentioned rooms, will remain fully satisfied by 10 [o'clock] so that they will leave the place free for intelligent and studious people».

Today this Museum is known as La Specola (‘the observatory’), since an astronomical observatory was also organised five years later in the same building. By the way, La Specola became world famous thanks to its unique collection of 1400 anatomical and zoological wax models, the largest in the world.

Joseph II, The Holy Roman Emperor

Visiting his younger brother Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, in Florence in 1769 and 1775, Joseph II (The Emperor of Holy Roman Empire, Archduke of Austria, King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia) viewed the famous Medici collection of rarities, and among them wax anatomical models. During his trips, Emperor Joseph II was accompanied by his personal royal surgeon Giovanni A. Brambilla, whose patient actually was Leopold himself when he was living in Vienna. Inspired by his brother's example and convinced by his personal medical advisor, the Emperor decided to provide the future Military Surgical Academy with innovative didactic tools and placed an incredible order.

Grand Duke Peter Leopold (left) with his brother Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, by Pompeo Batoni, 1769. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Credit: wikipedia

Production of the collection

The emperor's wish was not easy to fulfil. The wax exposition in Florence was not yet finished and, of course, it was not for sale. Moreover, the production of a second set in the same quantity could have jeopardized the main order for the Florence. However, Joseph II managed to persuade his younger brother and a way to create a second unique collection was found. The huge order required an expansion of production, so the court physicist Felice Fontana opened a second wax workshop in his own house, employing an additional 200 people.

Talented artists, anatomists, physiologists and historians laboured to create these models. Influenced by artistic traditions, the full-body figures used forms inspired by Michelangelo's sketches, often resembling the poses of saints or martyrs. As it is described in the 'The Josephinum : 650 years of medical history in Vienna' by B. Sternthal, the creation of wax models was an incredibly meticulous and labor-intensive process. It began with obtaining an exact anatomical specimen of a body region or organ. Due to the lack of preservation methods at the time, a single model could require up to 200 corpses or body parts. The initial step involved sculpting extremities, organs or parts in clay, which served as the basis for creating a plaster pattern — a negative mould used for the subsequent wax model.

After the plaster pattern dried, it underwent detailed corrections by anatomists and artists to ensure accuracy. The positive wax model was then cast from this mould, which was coated with oil or soap to seal the pores and allow for easy removal of the wax. This stage was particularly time-consuming, with each wax sculptor employing and refining their unique techniques over time.

The wax used for the models was a high-quality white wax sourced from wild bees originated from Eastern Europe, prized for its durability against temperature variations. As the wax was heated, substances like oil, lard, resin (from larch or pine), and pigments such as vermilion, earth tones, and red lead were mixed in to achieve the desired consistency and color. The mixture was poured in layers into the hollow plaster moulds. Once cooled, the molds were briefly immersed in cold water to facilitate the separation of the wax model from the plaster.

The finishing process was highly intricate. Surfaces were polished, and fine details were added using paints made from oil or resin. Additional pigments were applied to specific areas, followed by several layers of varnish. Blood vessels and tendons were sculpted and integrated into the model. In some cases, glass eyes and trimmed natural hair for eyelashes were incorporated to enhance realism. Finally, each model underwent rigorous quality control to ensure precision. The plaster moulds were carefully archived to enable future reproductions, preserving the intricate work for subsequent use – this enabled e.g. creation of the copies from La Specola to be made for the Josephinum.

Clemente Susini. Head and neck with blood vessels and nerves. Wax model presented in the Cagliari Museum. Credit: wikipedia

In addition to Fontana, the scientific accuracy of the works was monitored by the physician and anatomist Paolo Mascagni (who published the first complete description of the lymphatic system) and the young sculptor and wax modeller Clemente Susini, who from 1782 became head of the Officina ceroplastica fiorentina (Florentine wax-plastic workshop).

Activity in the workshop was arduous and took entire day in horrible conditions due to the toxicity of the substances used, such as solvents for wax and varnishes. The liquid used to preserve the corpses contained arsenic, which had serious consequences for Susini, who presumably suffered from chronic intoxication.

The collection of totally 1,192 anatomical wax models was valued at 30,000 guilders, an impressive sum for the time (equivalent to several million euros today). By 1784, after six years of painstaking work, the grandiose commission was completed. The fragile exhibits and the Venetian glass cabinets to display them were disassembled, carefully packed and set off on the long journey. An endless caravan of men and mules made the arduous journey from Florence to Vienna, crossing the Alps via the Brenner Pass. In Linz, the precious cargo was reloaded and travelled by water downstream along the Danube to Vienna.

The collection at the Josephinum

The Josephinum housed a total of 1,192 wax models, including 16 full-body figures, six of which were larger than life-size. These exquisite anatomical exhibits were displayed in ornate hand-blown Venetian glass vitrines decorated with veneered tulipwood panelling, rosewood boards and satin silk cushions, some of which were edged with gold and silver threads. The didactic purpose of the collection is served by coloured drawings and explanatory sheets in three languages - Latin with additional Italian and German commentary.

Although the Viennese wax models have much in common with their Florentine counterparts, there are also notable differences. For example, the collection includes Mascagni's pioneering research on the human lymphatic system, vividly depicted in the model ‘Man with the Lymphatic Vascular System’ and in some others. In addition, the Viennese collection includes an unprecedented 102 obstetrical models, making it the unique collection of its kind worldwide.

One of the rooms presenting the wax models and hole-body exhibits in The Josephinum, Vienna

Such a development was of fundamental importance for anatomy; as Goethe said, "anatomic wax models made it possible to obtain an accurate copy of the original which could be preserved indefinitely and with no smell."The importance of such a discovery is demonstrated by the success of anatomic wax modelling, especially in Italy, in the 18th century, soon after Zumbo's death in Paris.

Reference objects

The only one collection in the world can be compared with Josephinum's one is presented in La Specola, Florence, Italy. However, other gatherings or single specimens are on display in numerous museums around the world, including the museums of Cagliari, Bologna, Pisa, Padua, Modena, Leiden, Montpellier, including La Specola in Pisa, Josephinum in Vienna, Palazzo Poggi in Bologna, Science Museum in London, Semmelweis Museum in Budapest, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris.

Reference Literature

- The Josephinum : 650 years of medical history in Vienna, myth and truth. Editors Sternthal, Barbara; Drumi, Christiane; Stipsicz, Moritz. Vienna : Brandstätter. 2014. ISBN: 9783850338332

- The new Josephinum. Medical History Museum Vienna. Ed. Christiane Druml. Vienna, 2022. ISBN 978-3-200-08686-9

- Roberta Ballestriero. Storia della Ceroplastica. http://www.ginecologia.unipd.it/collezione/Storia%20Ceroplastica.htm

- Puccetti ML, Perugi L, Scarani P. Gaetano Giulio Zumbo. The founder of anatomic wax modeling. Pathol Annu. 1995;30 Pt 2:269-81. PMID: 8570279.

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre oder die Entsagenden. Stuttgart und Tübingen, 1821

- Lightbown RW. Gaetano Giulio Zumbo - I: The Florentine Period. The Burlington Magazine. Vol. 106, No. 740 (Nov., 1964), pp. 486+488-496.