Josephinum Medical History Museum in Vienna

The Josephinum, Medical History Museum Vienna

The Josephinum in Vienna is a renowned medical history museum situated in the historical building of the Medical-Surgical Joseph's Academy established in 1785 (according to other sources in 1784) under Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor. Today, the museum houses the collections of the Medical University of Vienna, celebrated for its one of the world's largest anatomical wax models collection, which were crafted between 1784 and 1786 by Florence masters including renowned Clemente Susini. These models provide detailed insights into human anatomy and have been pivotal in medical education. After comprehensive renovations, the Josephinum reopened its doors in September 2022, offering visitors a blend of historical artifacts and modern exhibitions that chronicle over 650 years of medical history.

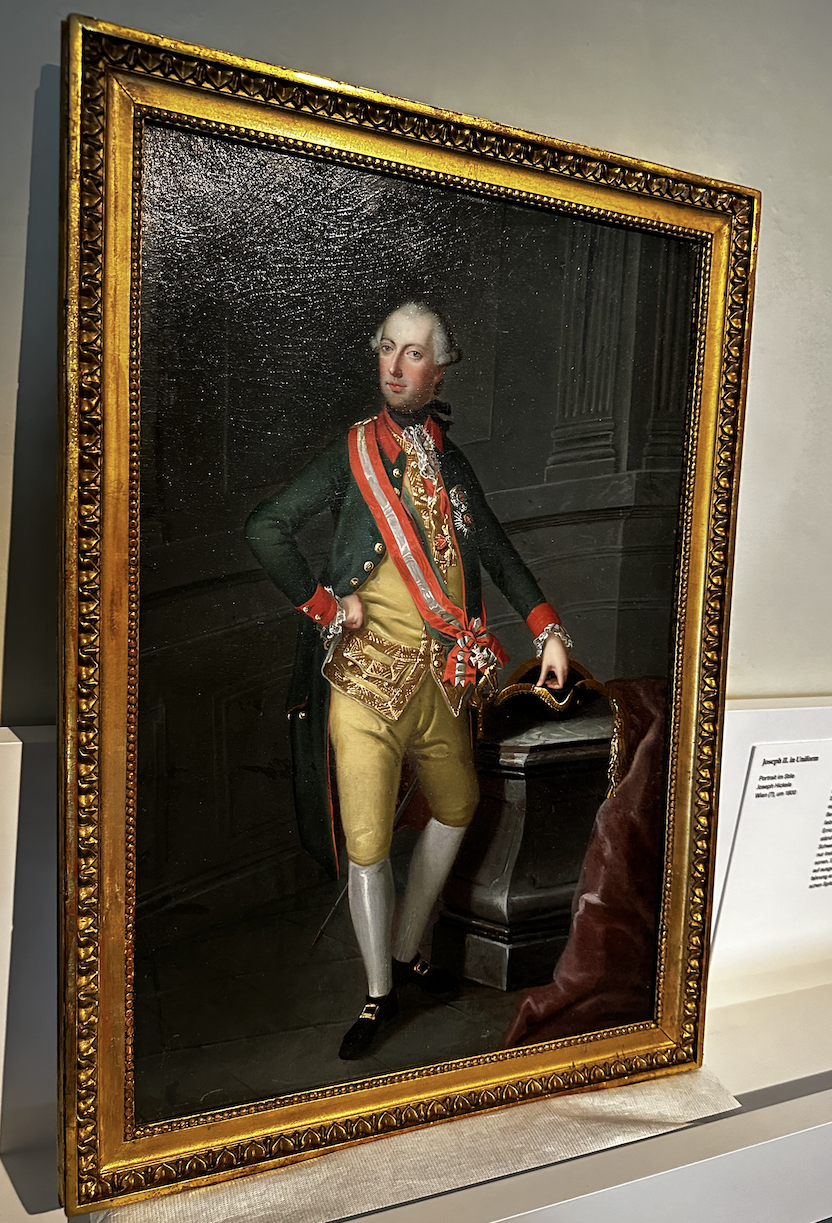

The portrait of the Josephinum's founder, Emperor Joseph II presented in the exposition

Why is it worth to visit?

A visit to the Josephinum in Vienna will provide you with a unique combination of historical, architectural and educational experiences. It was founded in 1785 by Emperor Joseph II as a medical-surgical academy in Vienna, officially called the "K.k. medizinisch-chirurgische Josephs-Academie" (Imperial and Royal Medical-Surgical Joseph's Academy). The building is a prime example of neoclassical architecture in Vienna, also called Josephinian Classicism or Plattenstil, reflecting the Enlightenment ideals of its time. It was created by court architect Isidor Ganneval within just two years, from 1783 to 1785.

The Academy was specifically designed for the education and training of military doctors and surgeons for the Austrian army in the latest science and practice level. Battlefield surgery has always been the focus of monarchs, and for the ambitious and educated reformer-emperor this field of medicine was the most important, providing a reliable rear support for his troops. Anatomy, the most important of the medical sciences for surgical practice, received a gift of unheard-of generosity from the emperor. In 1781, Joseph II commissioned 1,192 anatomical models made of color wax as a didactic core for the future lessons of the future military surgeons. The order crafted between 1784 and 1786 by Florence masters, and today this unique anatomical wax collection is the world's second largest one, only slightly behind the Florence museum La Specola.

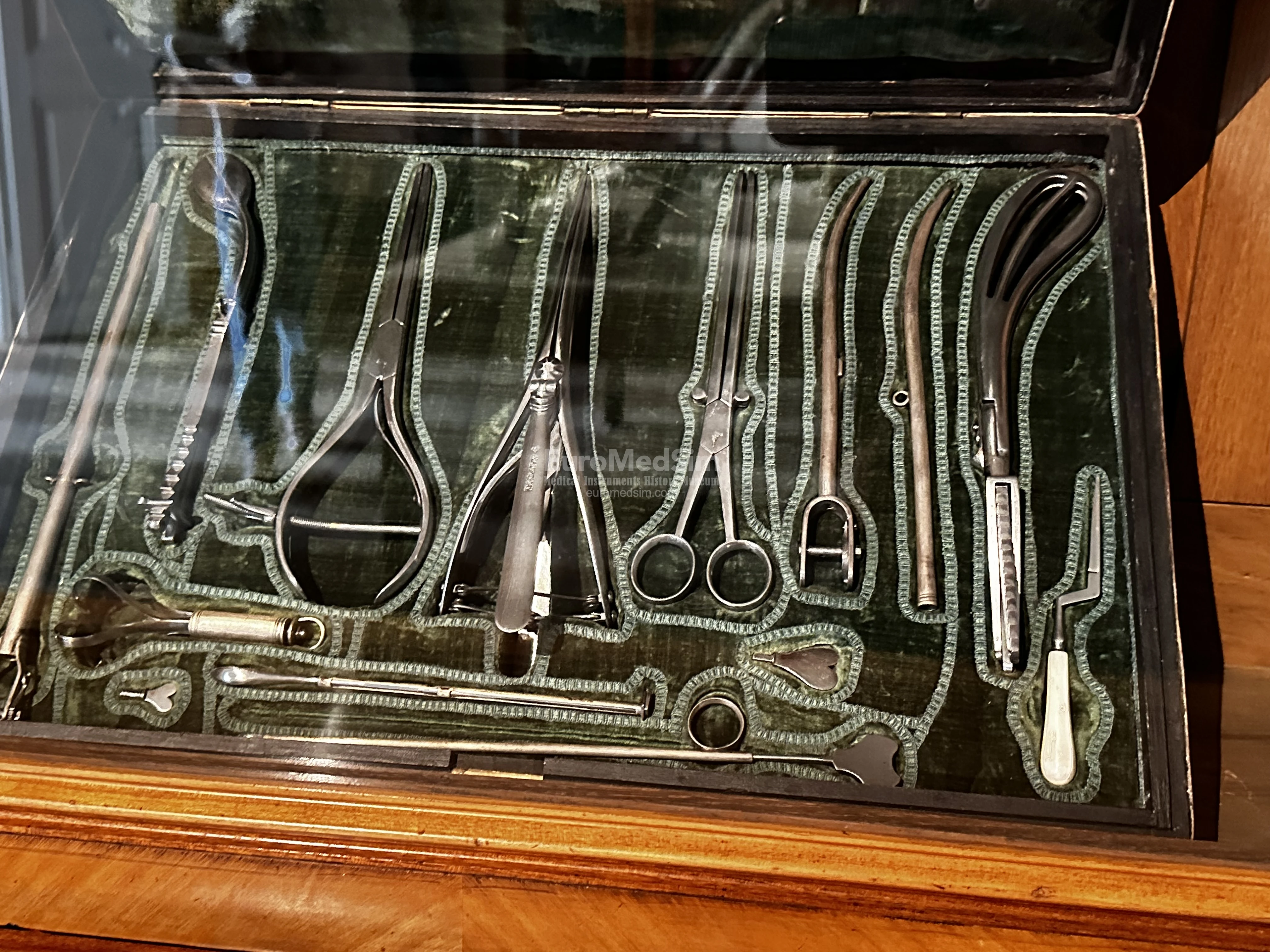

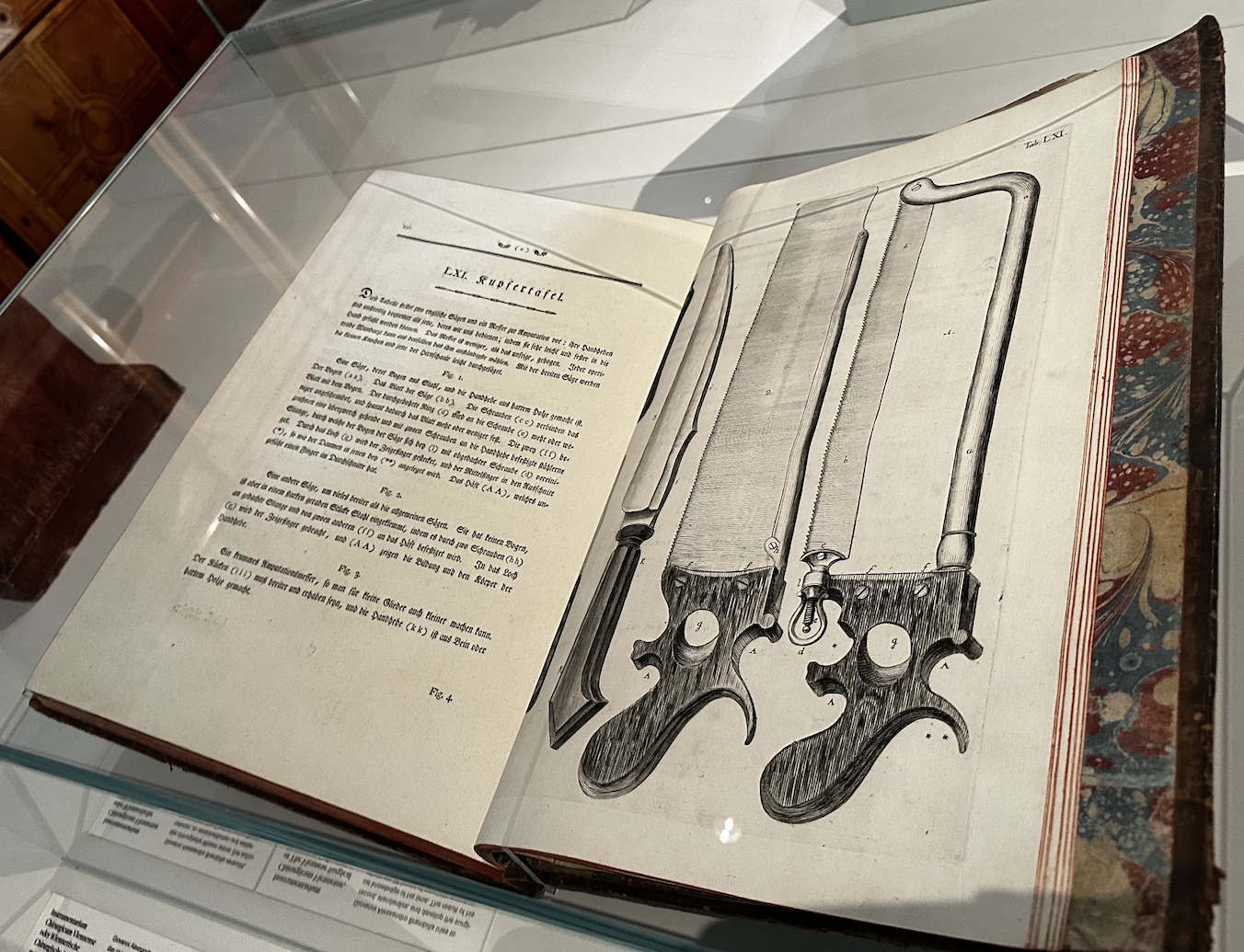

Beside of the its historical context, architectural beauty, and unique anatomy model collection, the Josephinum offers visitors a comprehensive view into the evolution of medical science and instruments evolution. Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla (1728-1800), emperor's personal surgeon and head of the entire Austrian military medical service (Protochirurg), was a key person in the creation of the Academy and served as its first director until 1795. In addition to his organisational talents, Brambilla became famous for a number of scientific and practical works. He left behind a collection of cased surgical instruments, also presented in the halls of the museum. His Instrumentarium chirurgicum militare Austriacum published in 1782 in folio contents 67 plates of engravings. It is the most complete survey of surgical and medical instruments of its time, illustrating over 600 instruments in actual size(!).

The 'Instrumentarium chirurgicum militare Austriacum', by Giovanni Brambilla, Vienna, 1782

The most important exhibits

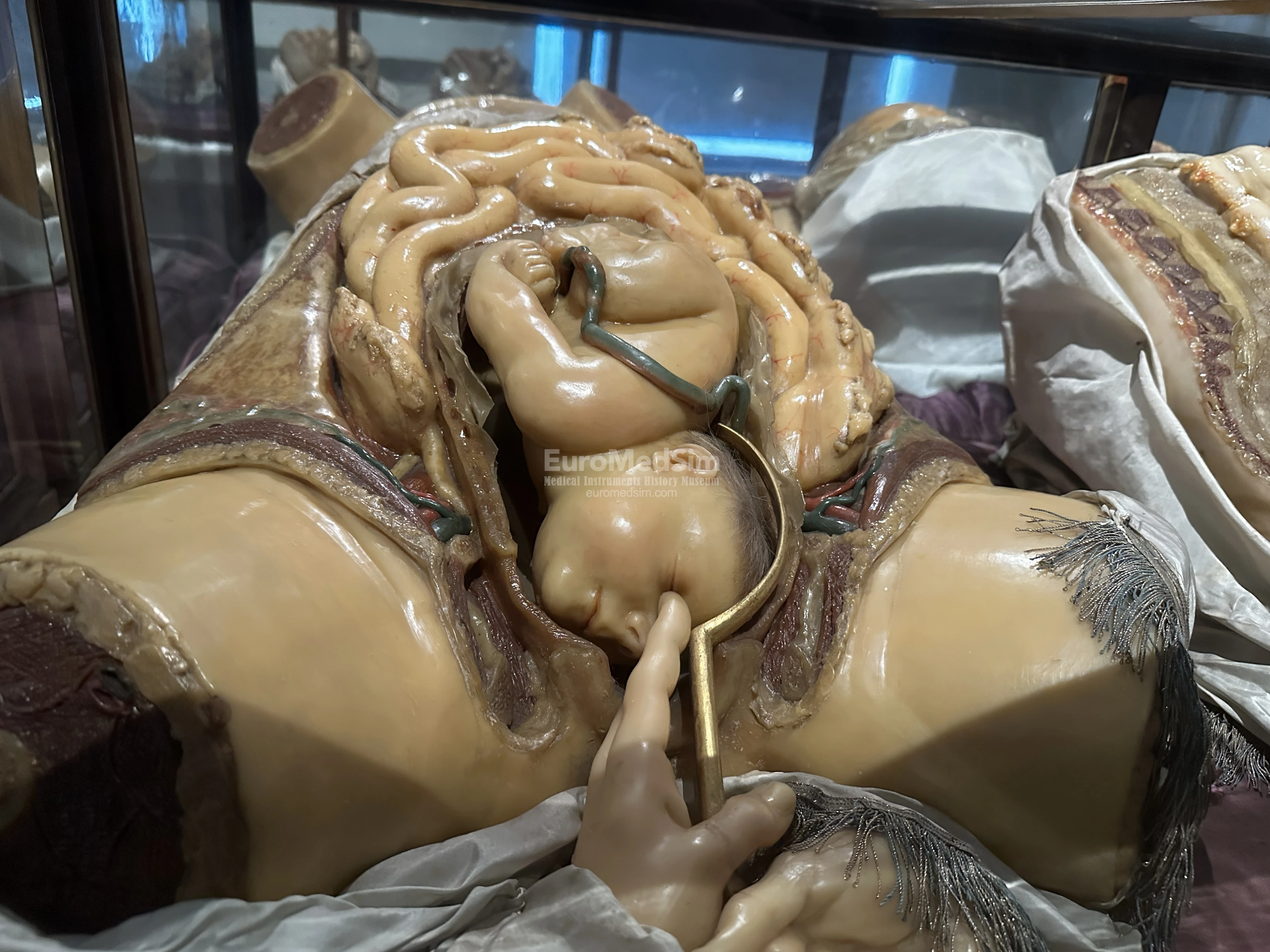

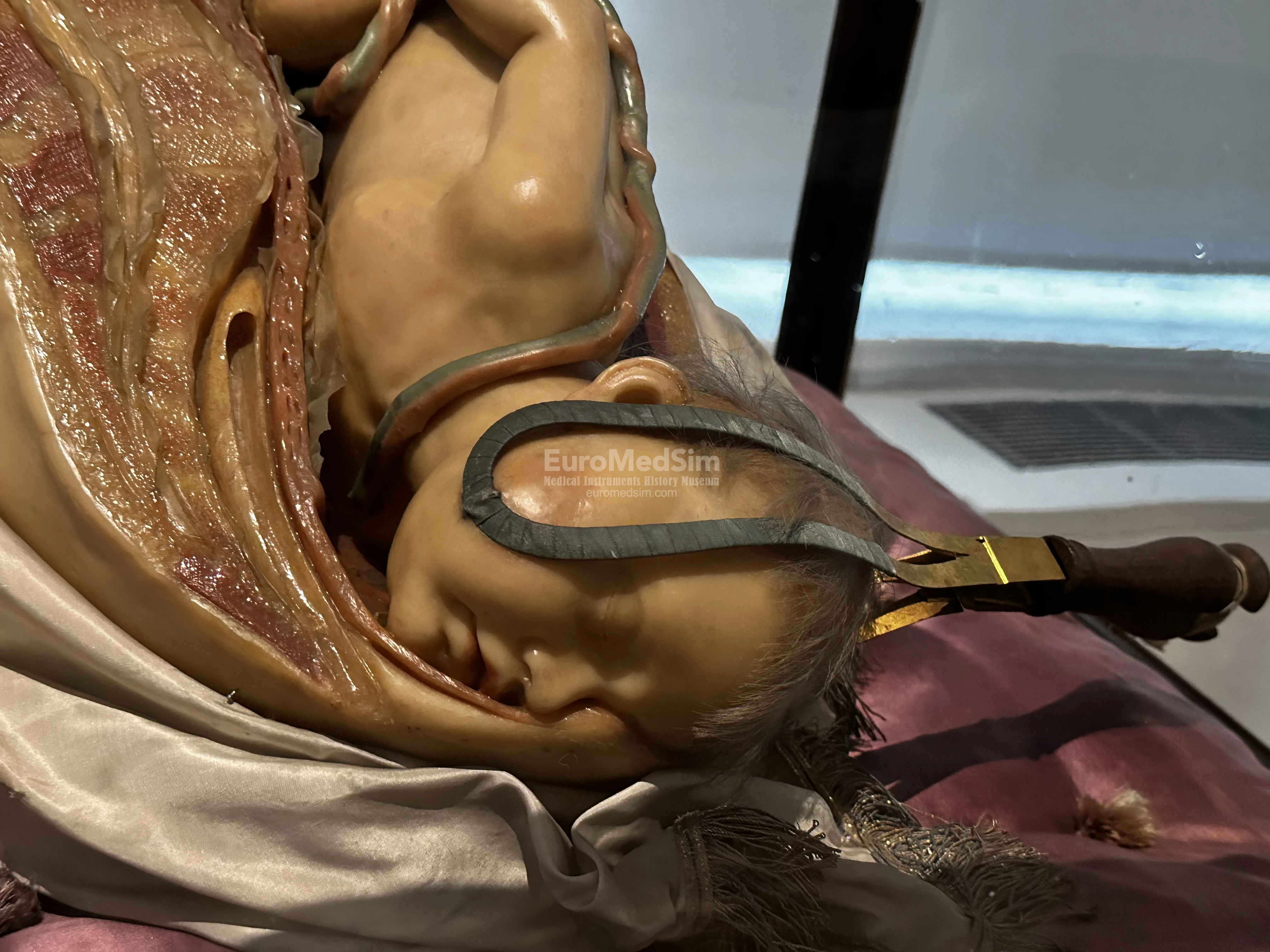

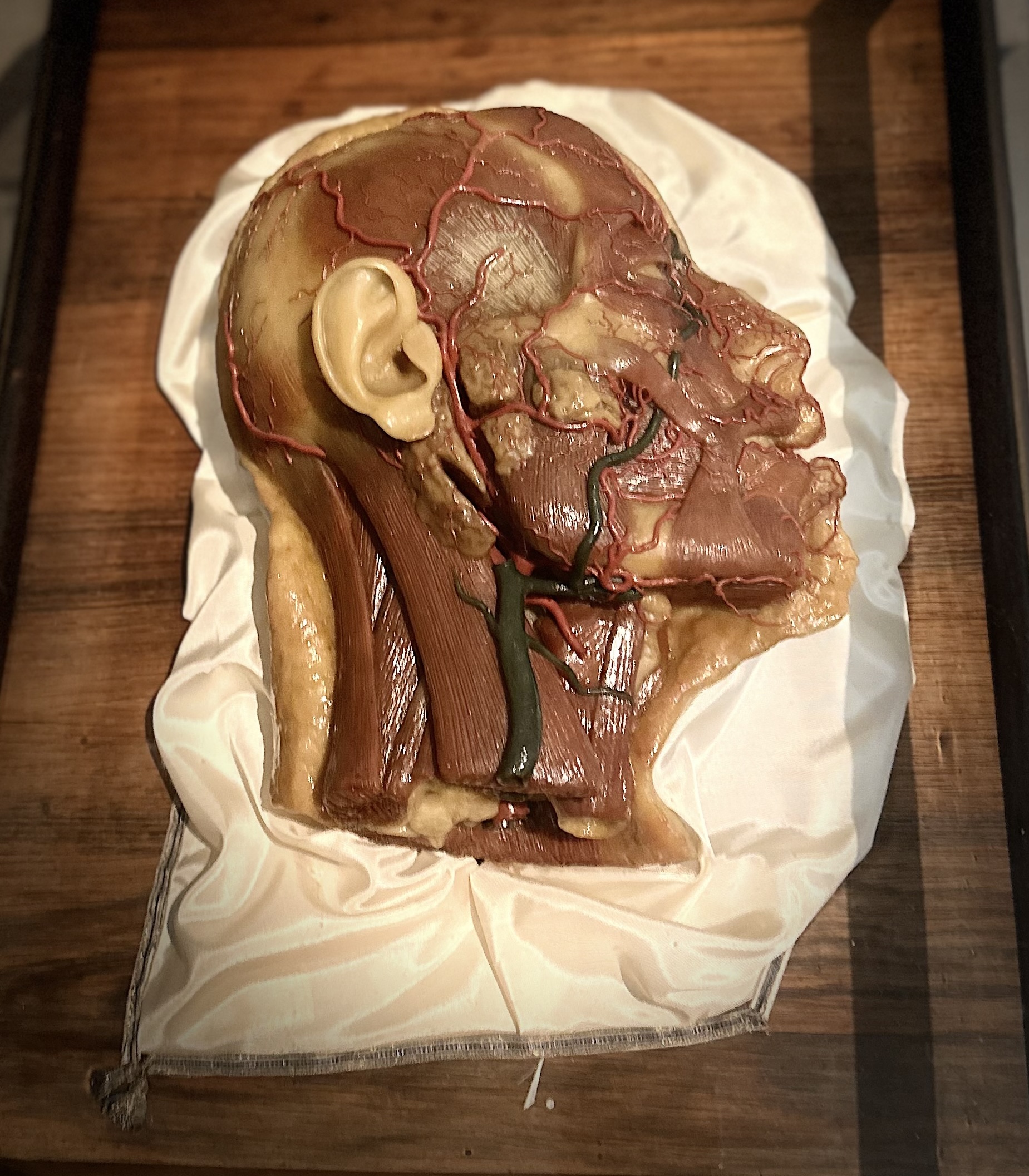

Collection of the wax anatomy models

During his travels to Italy in 1769 and 1775, Joseph II was inspired by the wax models he admired in the company of his brother Leopold, Duke of Tuscany. In 1781, the Emperor ordered a total of 1,192 anatomical objects for the future medical-surgical academy. The models were valued at 30,000 guilders, which was a considerable sum for those times (an equivalent to several million euros today). This huge order necessitated the expansion of production at the Florentine wax workshop headed by natural scientist Felice Fontana (the first curator of the Museum for Physics and Natural History, famous La Specola). The scientific precision of the works was supervised by physician and anatomist Paolo Mascagni (who published the first complete description of the lymphatic system) and involved modeller Clemente Susini, who later headed Officina cerooplastica fiorentina (The Florence wax plastic workshop).

The grandiose order was completed in 1784. The delicate exhibits and the vitrines made of Venetian glass for their display were carefully packed and set off on a long journey. The endless caravan of wagons and mules travelled from Florence to Vienna by a complicated route, crossing Alps via Brenner Pass. In Linz, the precious cargo was reloaded onto ships that travelled by water along the Danube to Vienna.

Today the unique collection of wax anatomical models is exhibited in the Josephinum Museum, and includes both full-grown models and individual parts and organs and systems. The exhibits are kept historically in original rosewood and Venetian glass cases.

Florentine ceroplastic models ordered by Joseph II

Surgical Sets of XVII century

Totally 45 'cassettes' with different types of surgical instruments. The sets were ordered by Brambilla and realised by Joseph Malliard (1748–1814), Austrian cutler, based on the drawings in his book 'Instrumentarium chirurgicum militare Austriacum'. The served for educational purposes by demonstration to the disciples of the Academy. Echt schade (it's a pity!) that most of them are presented with closed lids that do not allow to examine their content.

One of the 45 instruments' sets manufactured for Giovanni Brambilla by the Austrian surgical instrument manufacturer Joseph Malliard in the late XVIII.

History of the museum

1781. The Emperor Joseph II ordered 1,192 anatomical wax models from Florence, which were delivered in 1784, becoming a key part of the educational process of the time and today remaining one of the museum's main attractions.

1785. Founded by Emperor Joseph II in 1785 as a military surgical academy, it became at that time one of the world's leading centers for the training of battlefield medical specialists. Working alongside the academy's founder was his personal surgeon, Alessandro Giovanni Brambilla, who became the first director of the Josephinum (1785-1795). The academy building was designed by the court architect Isidor Gunnewal and built between 1783 and 1785 in Vienna's Alservorstadt (now the 9th district), becoming one of the most important examples of Austrian classicist architecture.

1786. Just after its opening on February 3, 1786, the Academy received the equal status to the other faculties of the University of Vienna and was granted the right to award the academical degree of Doctor of Medicine.

1808. The Chancellery of the Emperor Franz II allowed to hold the first lecture on the History of medicine hold at the Medical Faculty of the Vienna University (which was in fact taken place a year after).

1822. After the death of Joseph II, the government paid much less attention to the Academy. On the initiative of the then director Johann Nepomuk Isfordink, the Academy was equated with the universities of the Austrian Empire on October 27, 1822, and lectures were held until it was closed by Franz Joseph I in 1849.

1833. The Chair of Medical History was established in the Vienna University.

1848. The Academy was merged with the Vienna University according to decree of Emperor Ferdinand.

1852. The Academy was reopened on 15 January 1852 as an institution for field surgeons (Feldscherer) with the title of Military Medical Institute. On February 15, 1854 Emperor Franz Joseph declared separation of the Joseph Academy from the University.

1874. The Military Medical Institute as an independent educational body was closed on July 16, 1874. Later, military complementary education was added to classical university curriculum.

1919. Neurologist and later full professor in the field of history of medicine Max Neuburger, who had been collecting medical items, books and photographs since 1906, proposed the establishment of an Institute for the History of Medicine in 1914. It was grounded in 1919 and in the summer of 1920 he succeeded in relocating the Institute into the Josefinum building. Prof. Neuburger headed the Institute until his dismissal on racist grounds on April 22, 1938.

2004. The Medical Faculty of the University became independent organisation and in 2004 the Medical University of Vienna was established.

2022. In fact, since its founding, the Josephinum has served as a museum to varying degrees. In 2019, a major reconstruction began, postponed due to the pandemic until 2022 and costing 11 million euros. Since September 29, 2022, the building serves as a museum for the history of medicine with an expanded exhibition area of about 1,000 m² and houses the collections of the Medical University of Vienna and the library. In addition to the museum exhibition and library, the building houses the Institute for the History of Medicine of the Medical University of Vienna.

Architecture of Josephinium

The building of Josephinum represents an outstanding example of Neoclassical architecture in Vienna, often referred to as Josephinian Classicism or Plattenstil, embodying the Enlightenment principles of its era. Designed by the court architect Isidor Ganneval (also known as Isidore Canevale), the construction of the complex was remarkably swift, taking only two years, from 1783 to 1785. The Plattenstil was marked by its minimalist approach, emphasizing clean lines and a lack of ornate decoration. This was a departure from the elaborate designs of the earlier Baroque period. Buildings in this style were designed with practicality in mind, reflecting the Enlightenment ideals of reason and utility. While restrained, the style incorporated classical architectural elements such as columns and pediments, aligning with the broader neoclassical movement of the time.

The design of the educational complex incorporates the balance, symmetry, and clean lines characteristic of neoclassicism, a style inspired by the classical architecture of ancient Greece and Rome. The use of columns and pediments in the façade conveys a sense of order and grandeur, typical of the Enlightenment-era focus on structure and logic. The interior of the Josephinum complements its exterior with a logical and practical layout, accommodating lecture halls, libraries, and spaces for anatomical instruction. Original rosewood and Venetian glass display cases, used for housing the anatomical wax models, add a refined yet functional touch to the interior spaces.

Behind the Academy was built Garrison Hospital, which served both as a treatment and training facility. During the recent restoration of the Josephinum, a unique and historically significant lecture hall was meticulously reconstructed, highlighting its importance as an educational and architectural gem. This restoration aimed to revive the hall’s original design and function, providing modern visitors with a glimpse into the academic setting of the late 18th century. Today, the lecture hall stands not only as a reconstructed historical artifact but also as a functional space for public engagement.

Literature

The Josephinum : 650 years of medical history in Vienna, myth and truth. Editors Sternthal, Barbara; Drumi, Christiane; Stipsicz, Moritz. Vienna : Brandstätter. 2014. ISBN: 9783850338332