Wax anatomical models' collection in the Josephinum

Wax anatomical models collection in Josephinum, Vienna

The Josephinum is the owner of one of the world's largest collections of anatomical wax models from the 18th century, commissioned by the Austrian Emperor Joseph II. The order of 1,192 pieces was made between 1781 and 1784 and fulfilled in Florence under the supervision of the physicist, anatomist and naturalist Felice Fontana, physician and anatomist Paolo Mascagni, and modeller Clemente Susini. Today, the unique collection is on display at the Josephinum and includes full-length models as well as individual body parts, organs and systems. The exhibits are stored in original vitrines of rosewood and Venetian glass.

Wax anatomy models in Florence

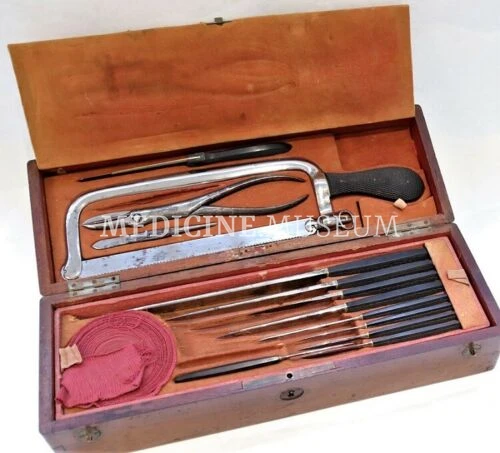

The study of anatomy had always a great challenge. Even after the dissections of the human cadavers were formally allowed, the unresolved problem of the source of cadavers and the conservation of the corps and anatomical specimens complicated the learning process.

Previously, teaching aids had been made of different materials including painted terracotta (fired clay). However, clay was too coarse material to represent small structures such as delicate blood vessels and nerves. These problems could be solved by coloured wax sculpture, a technique that had been known for quite some time.

In Florence, from the 13th to the 18th century, there was a whole industry of workshops producing wax statues of religious content as well as sculptures of real people to be presented as gifts (ex-voto) in church. The first wax anatomical sculpture was Lo Scorticato (Italian for exfoliated, skinned) by Ludovico Cardi surnamed Cigoli (1559-1613) - today it is in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence.

The next important step was taken by Gaetano Zumbo (1656-1701), who, during a five-year period working on Cosimo III de' Medici ’s Grand Duce, created several outstanding masterpieces, including the famous Head, an extremely realistic model with the skin removed, the skull sawed open and one hemisphere of the brain removed from the skull box, exposing its inner surface.

Gaetano Zumbo, the Head, wax anatomy model, 1697. Credit: wikipedia.

Peter Leopold, the Grand Duke of Tuscany

Directly related to the Josephinum is the Florentine workshop of ceroplastics founded by the polymath Felice Fontana (1730-1805), who, along with his studies in natural history and physics, was an outstanding anatomist.

In 1766 Fontana was appointed professor of physics at the University of Pisa and became the curator in Florence of a large collection of natural curiosities – fossils, animals, minerals and exotic plants –collected by several Medici generations. Discussing with the Grand Duke of Tuscany Peter Leopold the creation of a future museum of natural sciences on the basis of this collection, he proposed to supplement the exposition with new exhibits made of wax – anatomical and botanical models.

At first the sovereign was opposed to the idea, but he was later persuaded by a court scientist who argued that a complete collection of anatomical models would greatly expand or even replace the dissection of cadavers. Leopold was an intelligent man and had an open mind about the problems of science. But even a scientifically progressive man like him disapproved of the dissection of human cadavers, regardless of the purpose of the act. Fontana's arguments thus fell on prepared ground, and he took advantage of this dislike of the Duke by explaining to him that when all human anatomy was done in coloured wax, there would be no need to dissect cadavers for research purposes. On 21 February 1775 the Royal Cabinet of Physics and Natural History of Florence was opened (later the La Specola Museum), of which the ceroplasty workshop became a part.

Leopold as Grand Duke of Tuscany, portrait by Anton Raphael Mengs, 1770. Credit: wikipedia

Joseph II, The Holy Roman Emperor

Visiting his younger brother Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, in Florence in 1769 and 1775, Joseph II (The Emperor of Holy Roman Empire, Archduke of Austria, King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia) viewed the famous Medici collection of rarities, and among them wax anatomical models. During his trips, Emperor Joseph II was accompanied by his personal royal surgeon Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla, whose patient actually was Leopold himself when he was living in Vienna. Inspired by his brother's example and convinced by his personal medical advisor, the Emperor decided to provide the future Military Surgical Academy with innovative didactic tools and placed an incredible order.

Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, portrait by Anton von Maron, c. 1775. Credit: wikipedia

Production of the collection

The emperor's wish was not easy to fulfil. The wax exposition in Florence was not yet finished and, of course, it was not for sale. Moreover, the production of a second set in the same quantity could have jeopardized the main order for the Florence. However, Joseph II managed to persuade his younger brother and a way to create a second unique collection was found. The huge order required an expansion of production, so the court physicist Felice Fontana opened a second wax workshop in his own house, employing an additional 200 people.

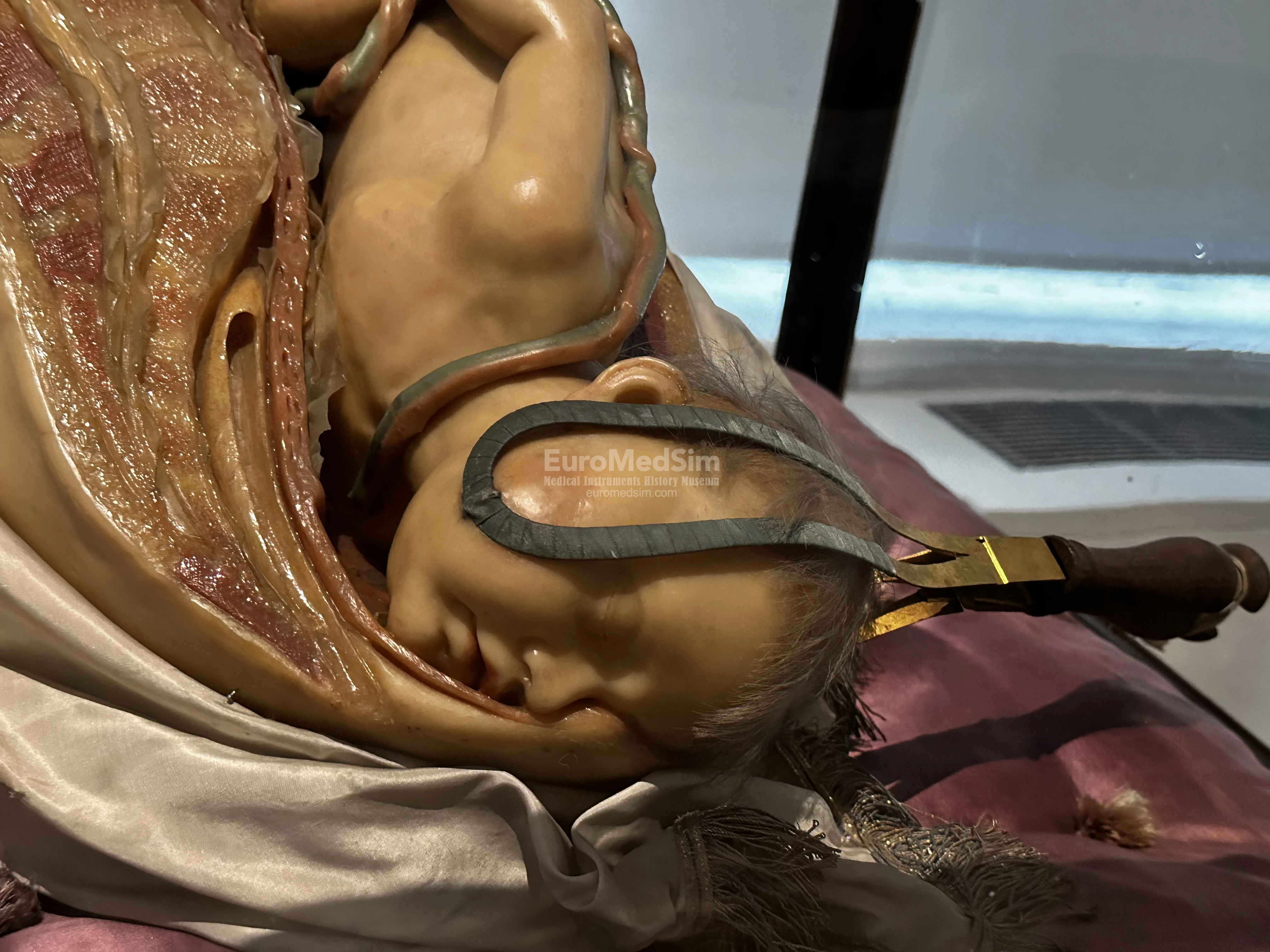

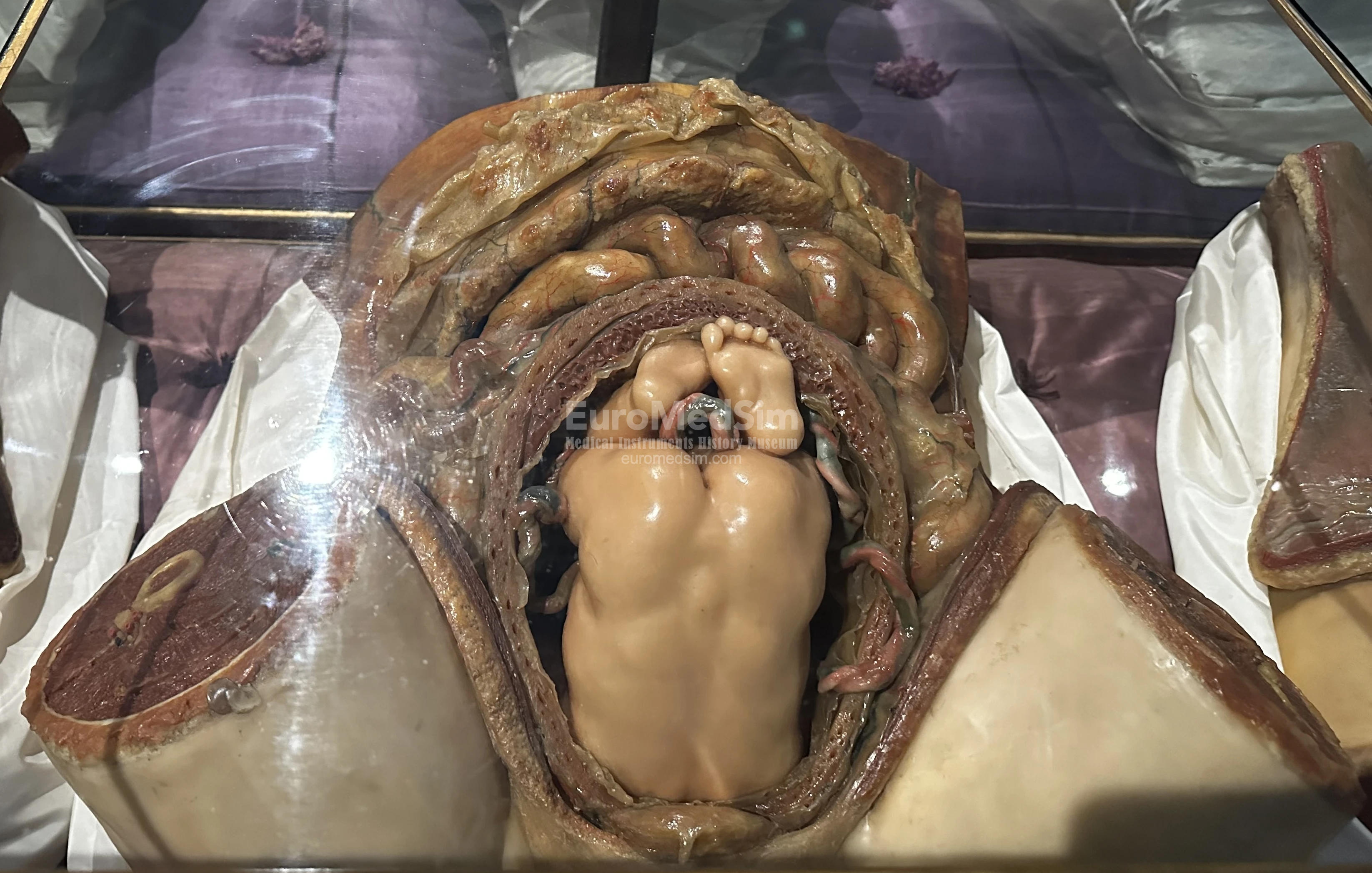

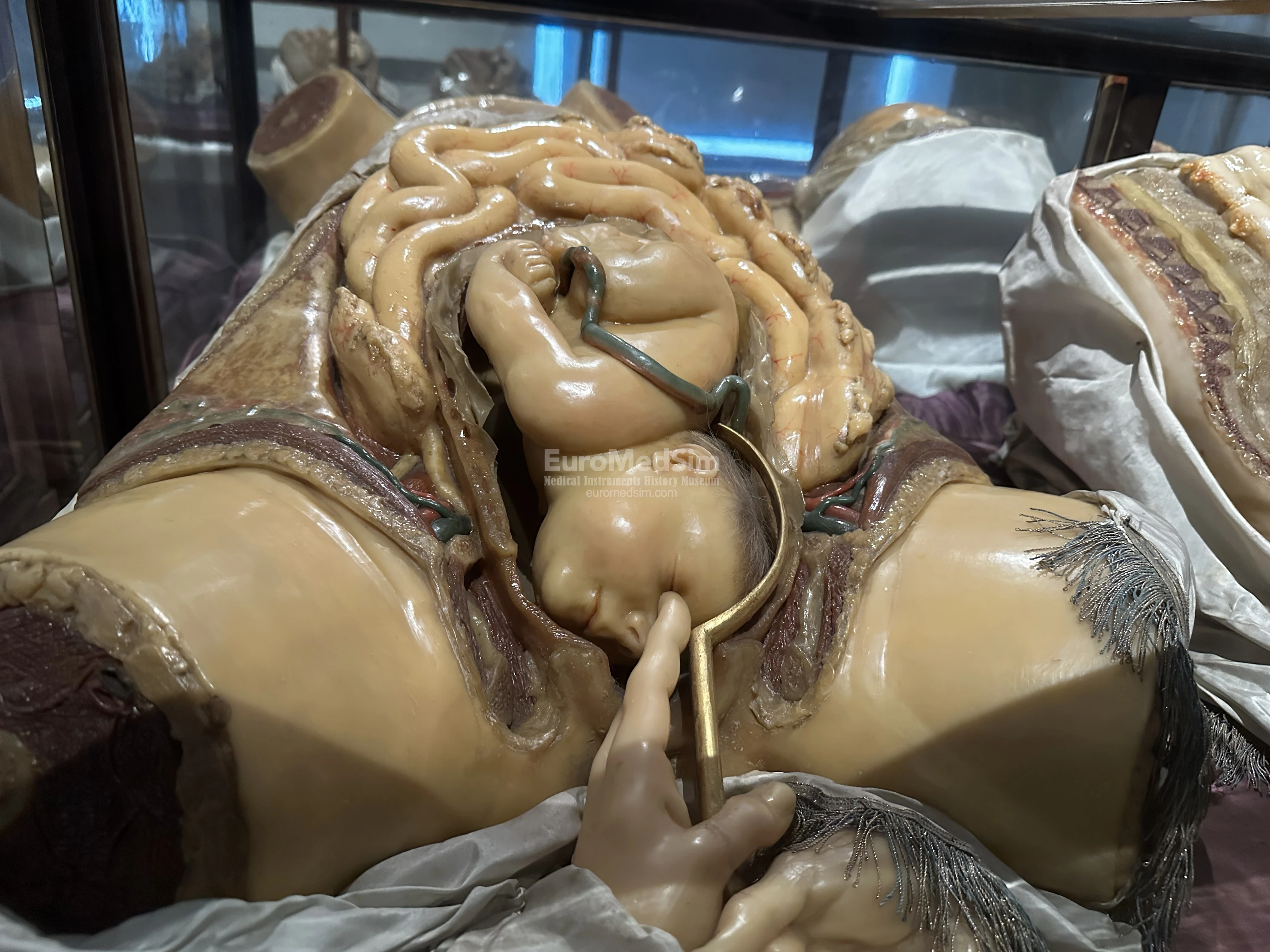

Talented artists, anatomists, physiologists and historians laboured to create these models. Influenced by artistic traditions, the full-body figures used forms inspired by Michelangelo's sketches, often resembling the poses of saints or martyrs. As it is described in the 'The Josephinum : 650 years of medical history in Vienna' by B. Sternthal (see References), the creation of wax models was an incredibly meticulous and labor-intensive process. It began with obtaining an exact anatomical specimen of a body region or organ. Due to the lack of preservation methods at the time, a single model could require up to 200 corpses or body parts. The initial step involved sculpting extremities, organs or parts in clay, which served as the basis for creating a plaster pattern — a negative mould used for the subsequent wax model.

After the plaster pattern dried, it underwent detailed corrections by anatomists and artists to ensure accuracy. The positive wax model was then cast from this mould, which was coated with oil or soap to seal the pores and allow for easy removal of the wax. This stage was particularly time-consuming, with each wax sculptor employing and refining their unique techniques over time.

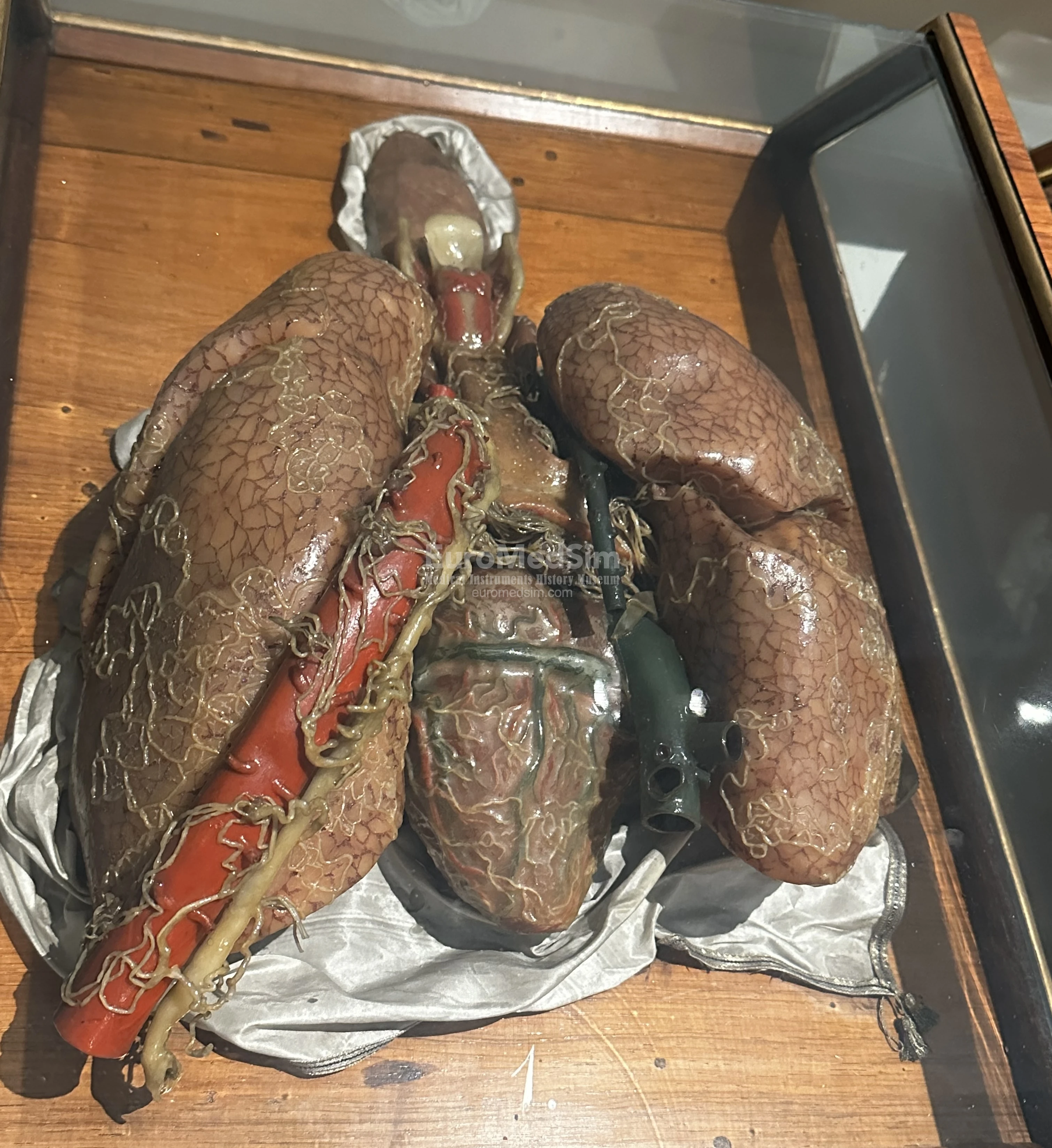

The wax used for the models was a high-quality white wax sourced from wild Ukrainian bees, prized for its durability against temperature variations. As the wax was heated, substances like oil, lard, resin (from larch or pine), and pigments such as vermilion, earth tones, and red lead were mixed in to achieve the desired consistency and color. The mixture was poured in layers into the hollow plaster moulds. Once cooled, the molds were briefly immersed in cold water to facilitate the separation of the wax model from the plaster.

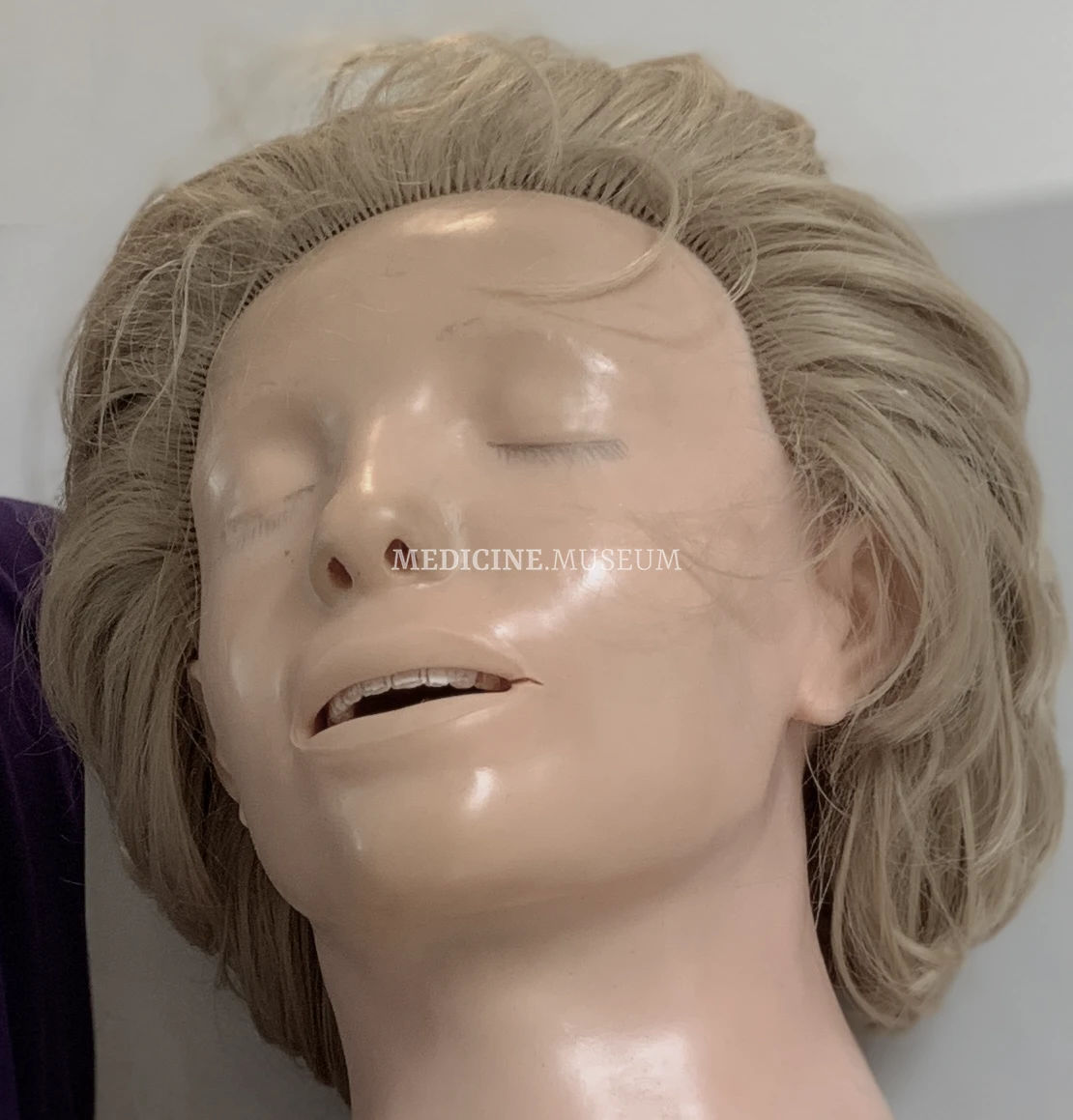

The finishing process was highly intricate. Surfaces were polished, and fine details were added using paints made from oil or resin. Additional pigments were applied to specific areas, followed by several layers of varnish. Blood vessels and tendons were sculpted and integrated into the model. In some cases, glass eyes and trimmed natural hair for eyelashes were incorporated to enhance realism. Finally, each model underwent rigorous quality control to ensure precision. The plaster moulds were carefully archived to enable future reproductions, preserving the intricate work for subsequent use – this enabled e.g. creation of the copies from La Specola to be made for the Josephinum.

Clemente Susini. Head and neck with blood vessels and nerves. Wax model presented in the Cagliari Museum. Credit: wikipedia

In addition to Fontana, the scientific accuracy of the works was monitored by the physician and anatomist Paolo Mascagni (who published the first complete description of the lymphatic system) and the young sculptor and wax modeller Clemente Susini, who from 1782 became head of the Officina ceroplastica fiorentina (Florentine wax-plastic workshop).

Activity in the workshop was arduous and took entire day in horrible conditions due to the toxicity of the substances used, such as solvents for wax and varnishes. The liquid used to preserve the corpses contained arsenic, which had serious consequences for Susini, who presumably suffered from chronic intoxication.

The collection of totally 1,192 anatomical wax models was valued at 30,000 guilders, an impressive sum for the time (equivalent to several million euros today). By 1784, after six years of painstaking work, the grandiose commission was completed. The fragile exhibits and the Venetian glass cabinets to display them were disassembled, carefully packed and set off on the long journey. An endless caravan of men and mules made the arduous journey from Florence to Vienna, crossing the Alps via the Brenner Pass. In Linz, the precious cargo was reloaded and travelled by water downstream along the Danube to Vienna.

The collection at the Josephinum

With their appearance, the medical school, advanced for its time, received a unique didactic material. Unlike the La Specola collection, the collection of wax anatomical models had a purely practical purpose – to teach anatomy to future military medical surgeons but not idle, albeit curious, philistines.

The Josephinum housed a total of 1,192 wax models, including 16 full-body figures, six of which are larger-than-life standing examples. These exquisite anatomical pieces were displayed in ornate Venetian hand-blown glass cases, adorned with veneered tulipwood facings, rosewood boards, and Atlas silk cushions, some fringed with gold and silver threads. Despite the tumultuous history of the Josephinum, many of these original display cases, along with their cushions and materials, have been preserved. However, the pedestals for the larger figures, which were once rotatable for anatomical teaching, have been replaced.

Vienna adopted Florence’s didactic approach to showcasing the models. The display cases could be opened, allowing Josephinum students to closely examine the intricate details of the wax figures. Accompanying the models were coloured drawings mounted on the walls above, while explanatory sheets in three languages—Latin with additional Italian commentary, also translated into German—were stored in drawers below.

Although the Viennese wax models share many similarities with their Florentine counterparts, there are notable distinctions. For instance, the collection highlights the groundbreaking research of Mascagni on the human lymphatic system, vividly depicted in the 'Lymphatic vessel system man' model and others. Additionally, Vienna’s collection includes an unparalleled number of obstetric models — 102 in total — making it the largest assemblage of its kind worldwide.

One of the rooms presenting the wax models and hole-body exhibits in The Josephinum, Vienna

Today, the wax models remain a remarkable example of an Enlightenment-era educational collection. Many of them have been preserved in excellent condition and are displayed in original rosewood and Venetian glass cases in seven rooms, preserving the historical and educational legacy of this extraordinary project.

Reference objects

The only one collection in the world can be compared with Josephinum's one is presented in La Specola, Florence, Italy. However, other gatherings or single specimens are on display in numerous museums around the world, including the museums of Cagliari, Bologna, Pisa, Padua, Modena, Leiden, Montpellier, including La Specola in Pisa, Josephinum in Vienna, Palazzo Poggi in Bologna, Science Museum in London, Semmelweis Museum in Budapest, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris.

Reference Literature

- The Josephinum : 650 years of medical history in Vienna, myth and truth. Editors Sternthal, Barbara; Drumi, Christiane; Stipsicz, Moritz. Vienna : Brandstätter. 2014. ISBN: 9783850338332

- The new Josephinum. Medical History Museum Vienna. Ed. Christiane Druml. Vienna, 2022. ISBN 978-3-200-08686-9