Wellcome Galleries of The Science Museum

The Science Museum in South Kensington is home to one of the world’s richest public collections devoted to medicine. Its centre‑piece since November 2019 is Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries, a £24 million suite of five halls that display more than 3 000 artefacts, immersive films and contemporary artworks across an area the size of 1 500 hospital beds. This magnificent setting positions London as custodian of a material record that ranges from medieval amputation saws to cutting‑edge robotic surgery consoles.

Welcome to The Science Museum. World of Science History, Presence and Future in London's South Kensington. The Science Museum, London, UK. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov

Origins of the collection

The roots of the galleries lie in the restless collecting of the American‑born pharmaceutical entrepreneur Sir Henry Wellcome. By 1913 his private Historical Medical Museum already brimmed with objects—“statues, masks … even steam engines,” as one contemporary observed—assembled in the belief that the whole story of healing could be told through things. After Wellcome’s death the holdings passed to the Wellcome Trust, which in 1976 placed the core of the collection on permanent loan to the Science Museum, doubling the museum’s footprint overnight and prompting the first dedicated medical displays in 1980.

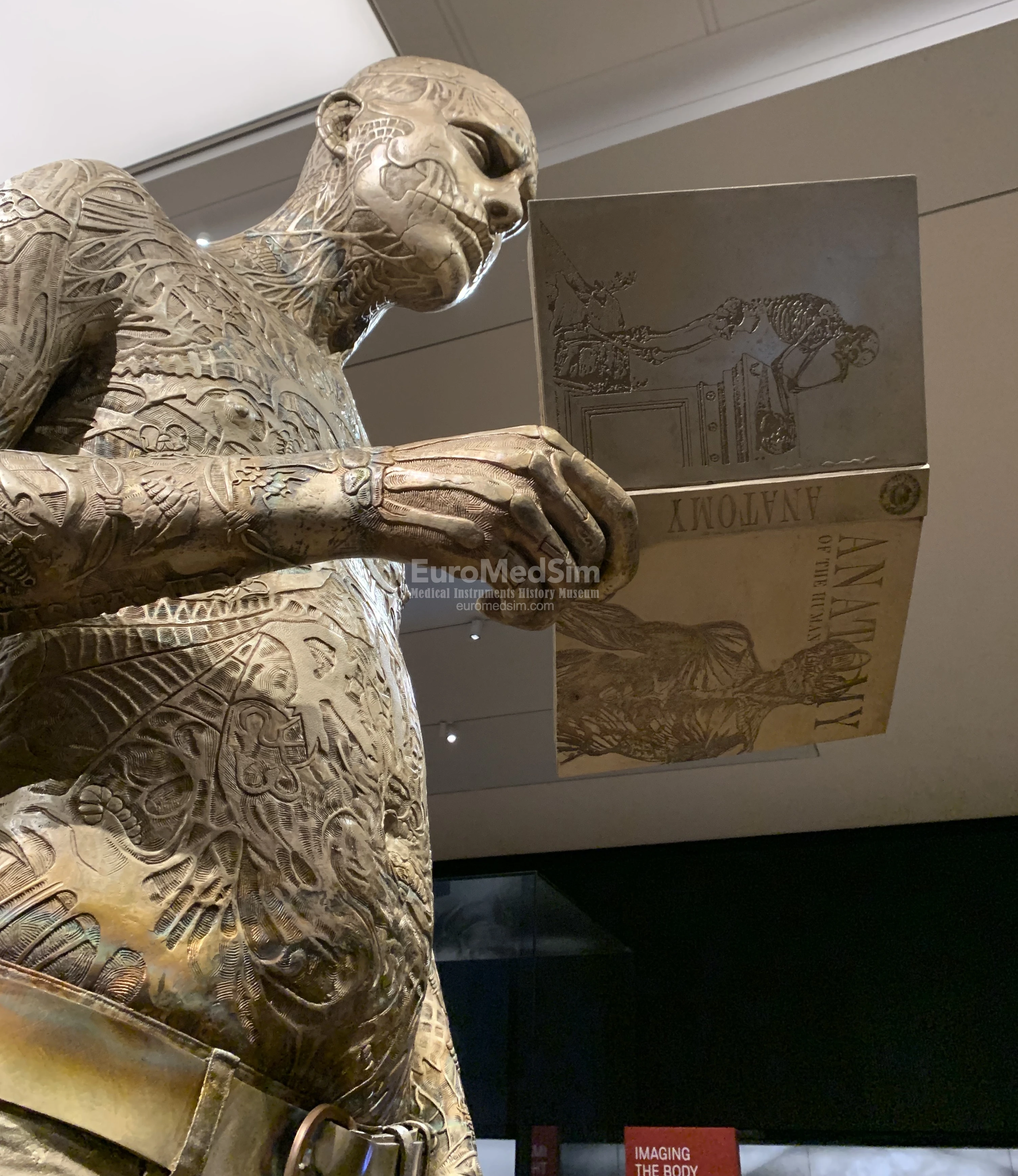

Entrance to the Wellcome Galleries of The Science Museum. The 'Zombie Boy' is meeting visitors. The Science Museum, London, UK. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov

Building the modern galleries

A generation later curators set out to replace those dated dioramas with an experience equal to the scale and diversity of twenty‑first‑century medicine. Designers WilkinsonEyre hollowed out the entire first floor to create a fluid narrative organised around themes — Bodies, Exploring Medicine, Medicine and Communities, Faith, Hope and Fear, and Medicine and Treatments. The result, opened by HRH the Princess Royal, is now billed by the museum as “the world’s largest medical galleries,” reinforcing London’s claim to global leadership in medical heritage.

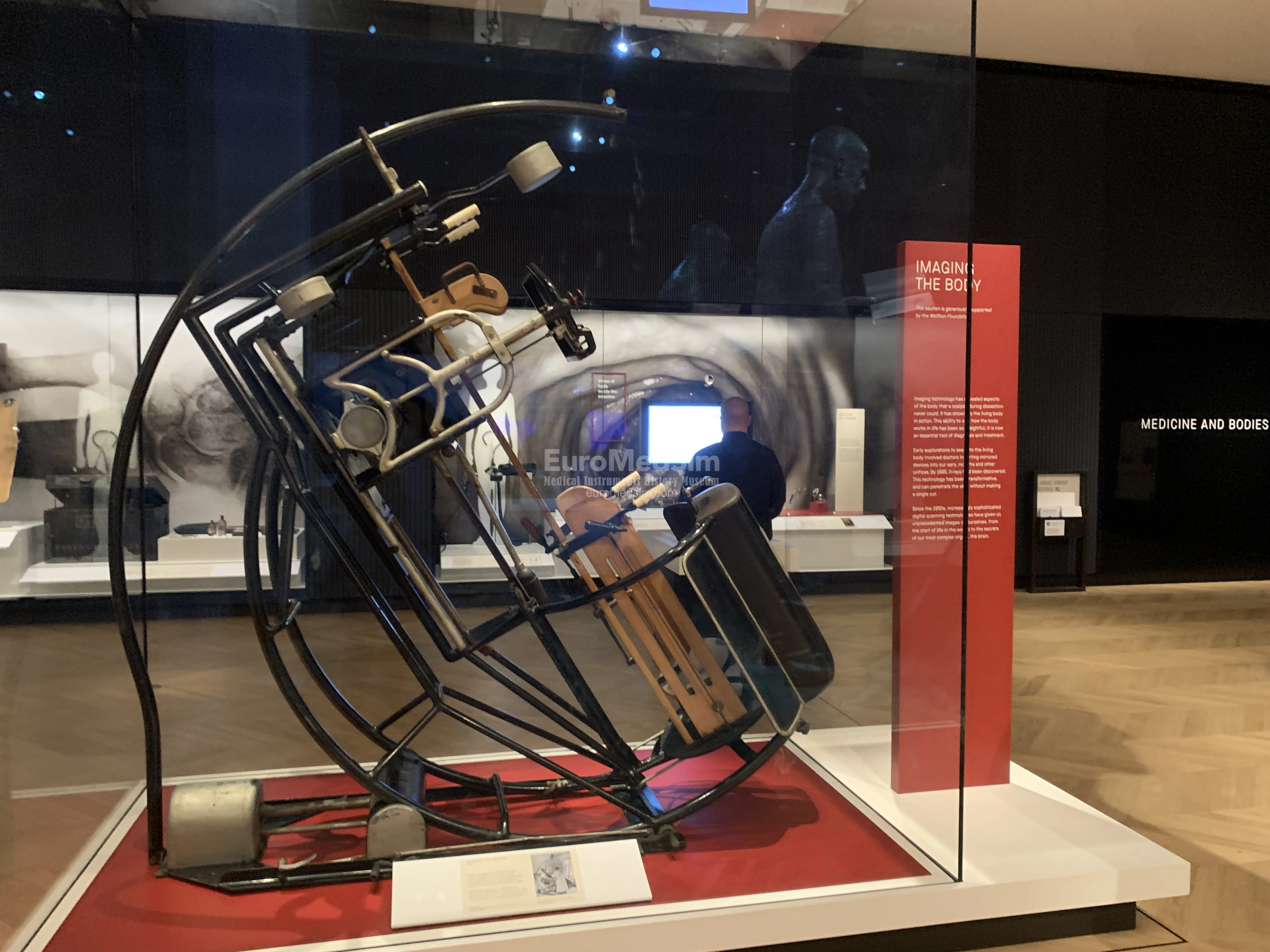

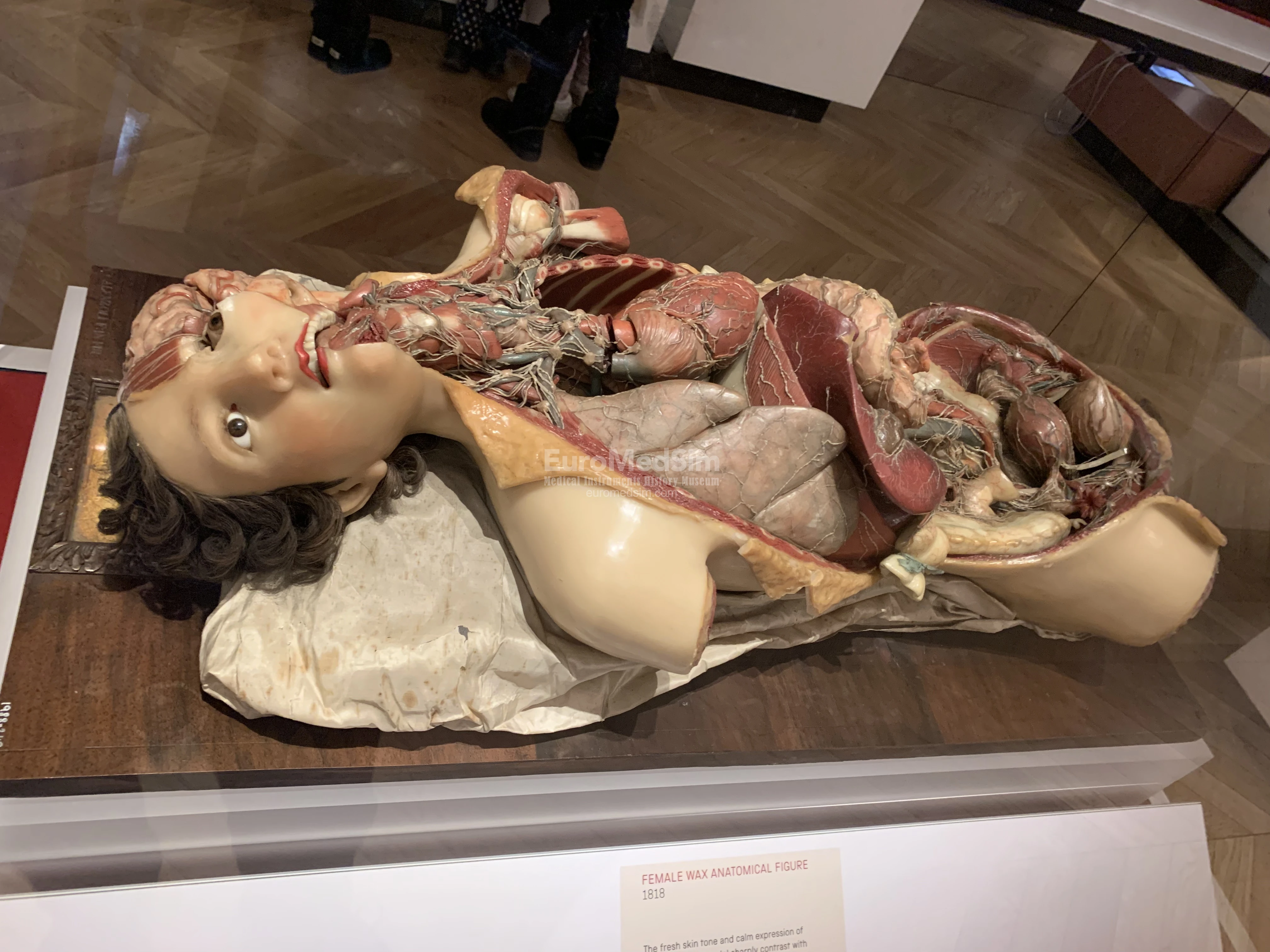

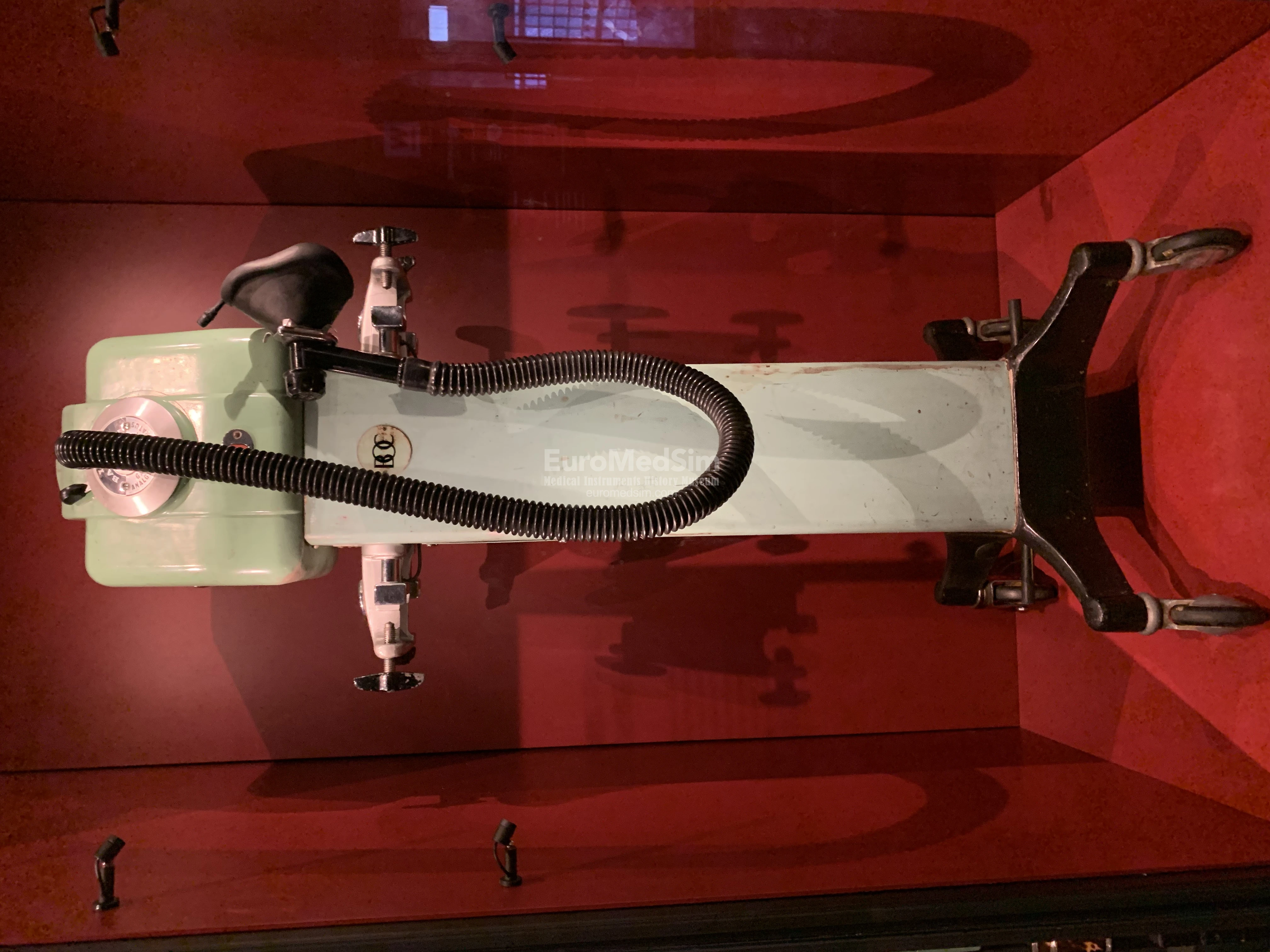

Iron Lung (Negative Pressure Ventilator), was used to treat patients—especially children—suffering from paralytic polio, a viral disease that could cause life-threatening respiratory failure. Known as an "iron lung," the device enclosed the patient's body and used negative pressure to simulate natural breathing by rhythmically expanding and contracting the chest. Widespread in the mid-20th century, especially during polio epidemics, iron lungs became essential in intensive care before the development of modern positive-pressure ventilators and widespread vaccination programs in the late 1950s and 1960s drastically reduced polio cases. The Science Museum, London, UK. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov

Public impact

Scale alone does not explain the galleries’ influence. Free entry draws well over a million visitors a year, from GCSE students wrestling with vaccination ethics to clinicians debating the future of AI diagnostics beside the very first MRI scanner. Digital cataloguing has also released more than 140 000 medical objects online, giving researchers on six continents access to primary material without leaving their desks. Teachers cite the galleries’ object‑rich approach—letting pupils handle a 1970s cardiac stent or compare woodcuts with modern CT scans—as a uniquely powerful way to connect STEM learning with social history.

Amputation Saw, 16 cent. Saws such as this one were used to cut bone as quickly as possible after the skin and muscle were cut away by knives. Before the introduction of pain relief and infection control in the mid-1800s, speed was a surgeon's only means of ensuring a patient survived an amputation. The stump was then dressed with water, wine and herbal lotions, before the long healing process began. The Science Museum, London, UK. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov

Amputation Saw, 16 cent. Saws such as this one were used to cut bone as quickly as possible after the skin and muscle were cut away by knives. Before the introduction of pain relief and infection control in the mid-1800s, speed was a surgeon's only means of ensuring a patient survived an amputation. The stump was then dressed with water, wine and herbal lotions, before the long healing process began. The Science Museum, London, UK. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov

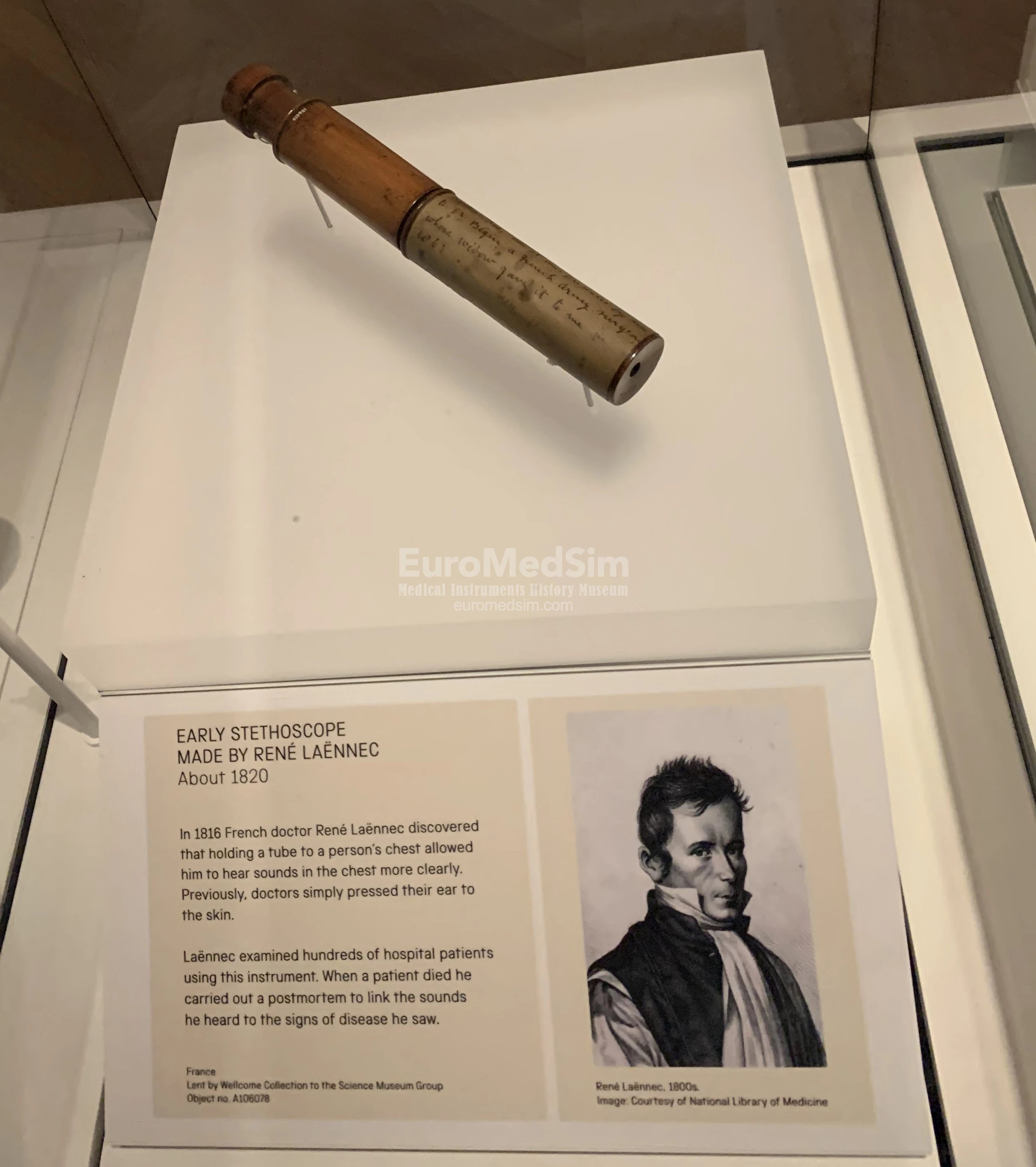

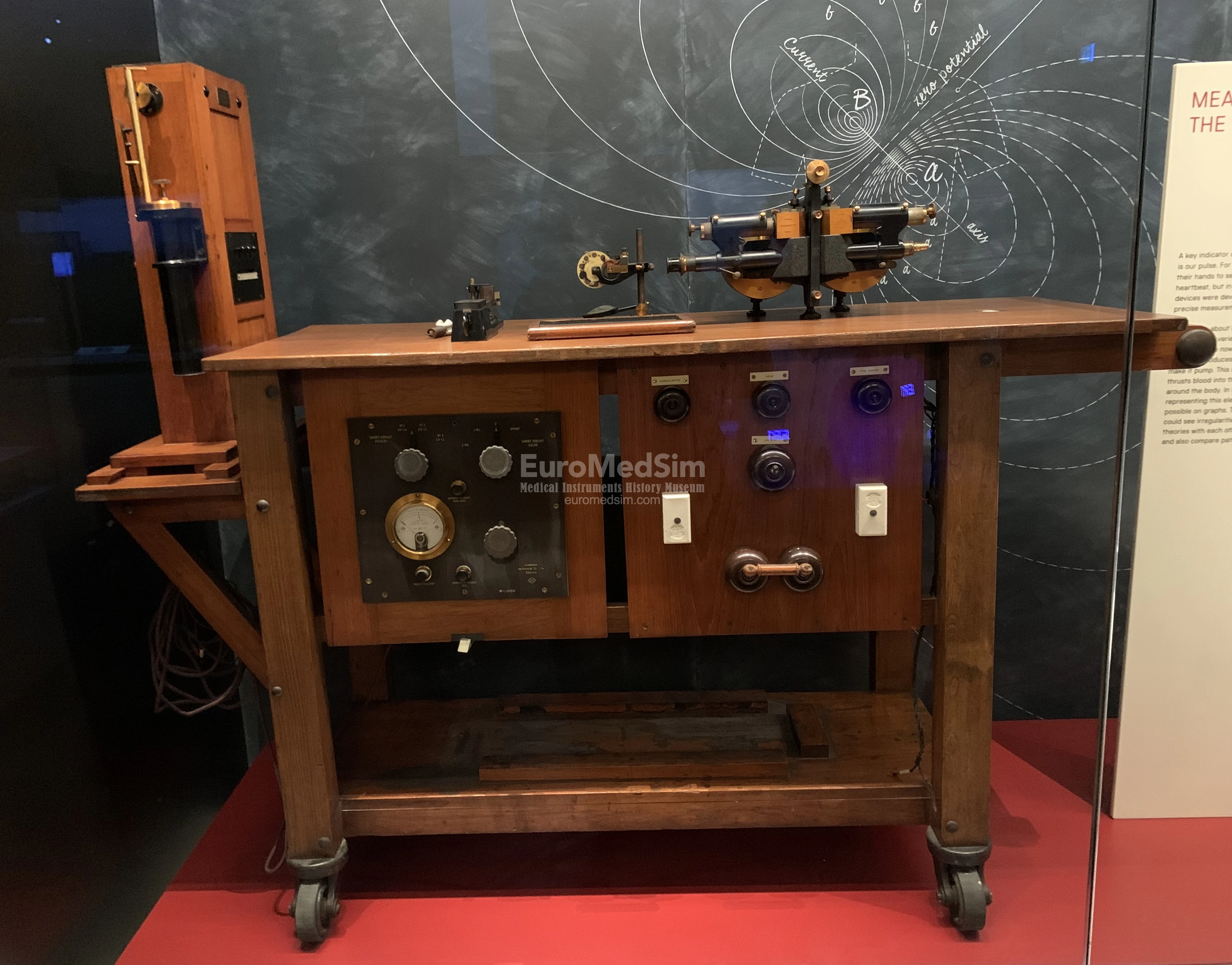

Icons and treasures

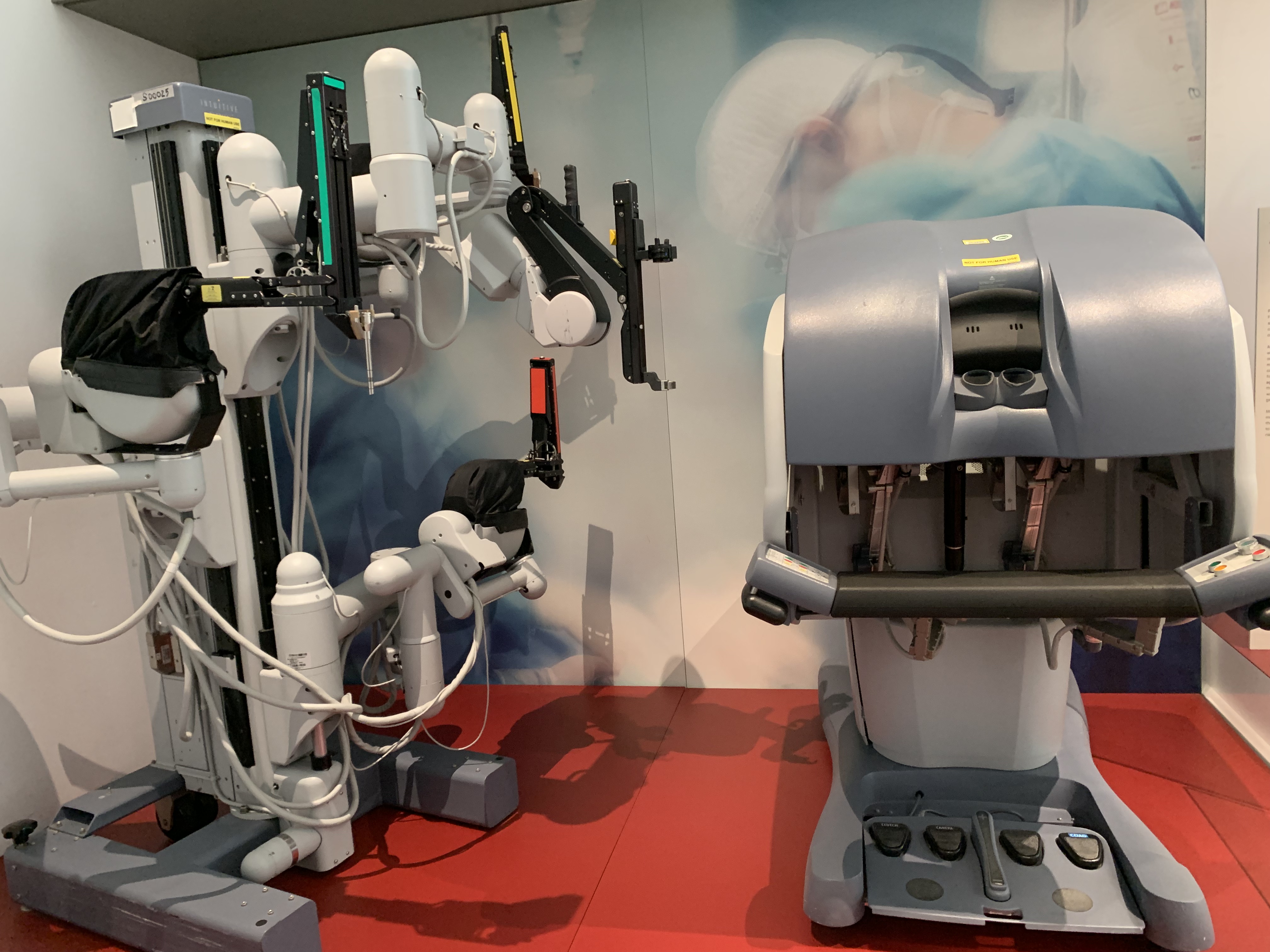

Among the thousands of objects a handful have near‑mythic status. The first whole‑body MRI scanner (installed at Hammersmith Hospital in 1982) stands like a white submarine hull, a reminder of how imaging revolutionised diagnosis. Nearby, Alexander Fleming’s own sample of Penicillium mould, given to a colleague in 1935, embodies the antibiotic era in a speck of green fuzz. A simple wooden tube represents René Laennec’s pioneering stethoscope of c. 1820, while a brass lancet used by Edward Jenner to administer the first smallpox vaccine recalls one of public health’s greatest victories. Large‑scale technologies have a place too: a full‑size iron lung evokes the terror of mid‑century polio wards, and a 2004 da‑Vinci surgical robot invites visitors to try key‑hole manoeuvres with haptic controls. More intimate is the 1904 pianist’s prosthetic arm, whose splayed wooden fingers could span an octave, proof that assistive design can also serve art.

da Vinci Surgical System – Surgeon Console by Intuitive Surgery Inc. USA, a state-of-the-art robotic platform used for minimally invasive surgery. From this seated position working-place (right), the surgeon operates robotic arms with precision hand controls and foot pedals, while viewing a high-definition 3D image of the surgical site. The working manipulators (left) were inserted into the patient and replicated the movements of the surgeon. Introduced in the early 2000s, the system enhances dexterity, vision, and control, enabling complex procedures through tiny incisions with reduced recovery time. The Science Museum, London, UK. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov

A living collection

The museum continues to collect. During the COVID‑19 pandemic curators acquired homemade ventilators and even Grayson Perry’s ceramic guardian “Alan Measles—God in the Time of Covid‑19”, ensuring the galleries remain a dialogue between past and present. Behind the scenes, the new Hawking Building at Wroughton secures long‑term conservation for a further 300 000 stored objects and opens study rooms to the public.

The collection of various antique instruments — mostly dental extractors like keys, forceps, and pelicans for tooth extraction, dated 18-19 cent. The Science Museum, London, UK. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov

In a city crowded with cultural landmarks the Science Museum’s medical collection stands out for the sheer density of human stories it contains. Whether confronting an iron lung or marvelling at the elegance of a violin‑shaped prosthesis, visitors leave reminded that medicine is never only a technical pursuit; it is a social contract, and every object—scalpel, scanner or sculpture—is a witness to changing ideas of care. That enduring capacity to connect science, ethics and lived experience is the collection’s most valuable exhibit of all.

Feeding or Medicine Pewter Spoons with Decks. These 17th–19th century spoons feature wide, covered bowls—often crafted from pewter—to regulate the delivery of liquids. Used in hospitals and home care, they served for feeding weak or bedridden patients, or administering medicinal broths and tonics. Their design reflects early innovations in caregiving tools aimed at comfort, precision, and hygiene. The Science Museum, London, UK. Photo: Maxim Gorshkov