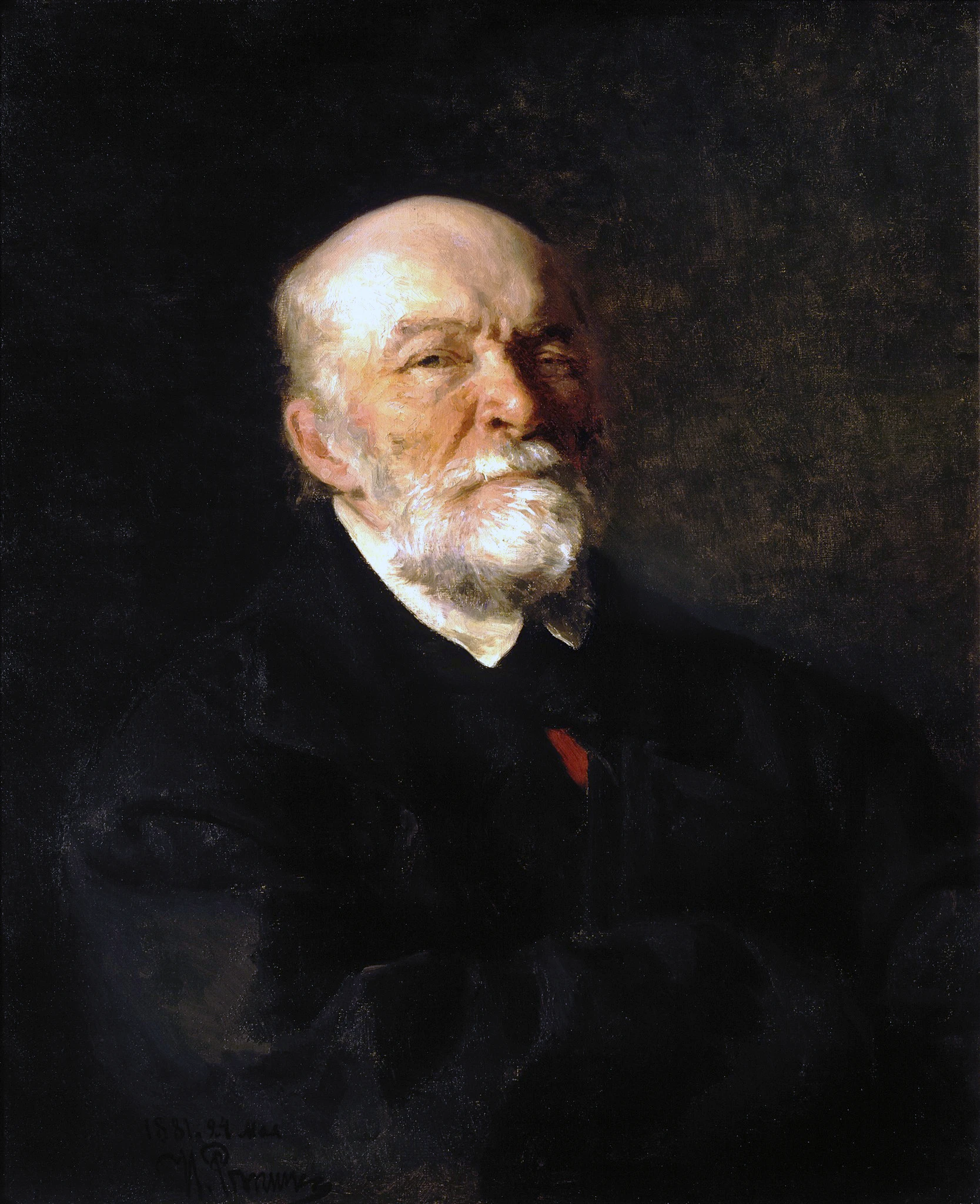

Halsted, William Steward

William Stewart Halsted (1852–1922) was an American surgeon, born in New York City, and one of the “Big Four” founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. He studied medicine at Columbia University (graduating in 1877) and refined his skills in Europe (1878-1880), especially in Vienna, and Leipzig, where he observed leading European surgeons. Returning to the U.S., he adapted German system of surgeons' training introducing the first American surgical residency program at Johns Hopkins in 1889, pioneered aseptic surgical techniques, and established the Halstedian principles: gentle tissue handling, meticulous hemostasis, and layered wound closure. In 1889, he also became the first Chief of Surgery at Johns Hopkins. Halsted introduced rubber surgical gloves (1890), initially to protect his nurse and future wife from skin irritation. He also made major contributions to breast cancer surgery (radical mastectomy) and the use of local anesthesia, though his experiments led to lifelong cocaine and morphine addiction. His achievements are confirmed by numerous honorary titles awarded to him by leading surgical societies and universities: Hon FRCS (July 25, 1900), Hon LLD Yale (1904), Hon DSc Columbia (1904), Hon FRCS Edin (1905). Halsted died in 1922 in Baltimore, leaving a legacy as the architect of American modern surgical training and technique.

A Young Doctor Abroad

After graduating from Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York (1877), William S. Halsted took a step that was common for young American surgeons in those years — he went to Europe to continue his medical education (1878–1880). At that time, Germany was the center of modern surgery. Bernhard von Langenbeck (Charité, Berlin, Germany) created the residency-style “house staff” system, and Theodor Billroth — his famous trainee — passed those ideas on. Halsted closely observed the work and educational principles of Europe’s foremost surgical schools, led by beacons such as Theodor Billroth, Jan Mikulicz-Radecki (Vienna, Austria), Ernst von Bergmann (Würzburg, Germany), Paul von Bruns (Tübingen, Germany), Karl Thiersch (Leipzig, Germany), Richard von Volkmann (Halle, Germany). He also popped over for shorter visits with Max Schede (Hamburg, Germany) and Johann von Esmarch (Kiel, Germany).

Across these centres, a common ethos prevailed: mastery of surgery required profound theoretical knowledge, meticulous anatomical study, and uncompromising technical precision.

Back Home, New Principles

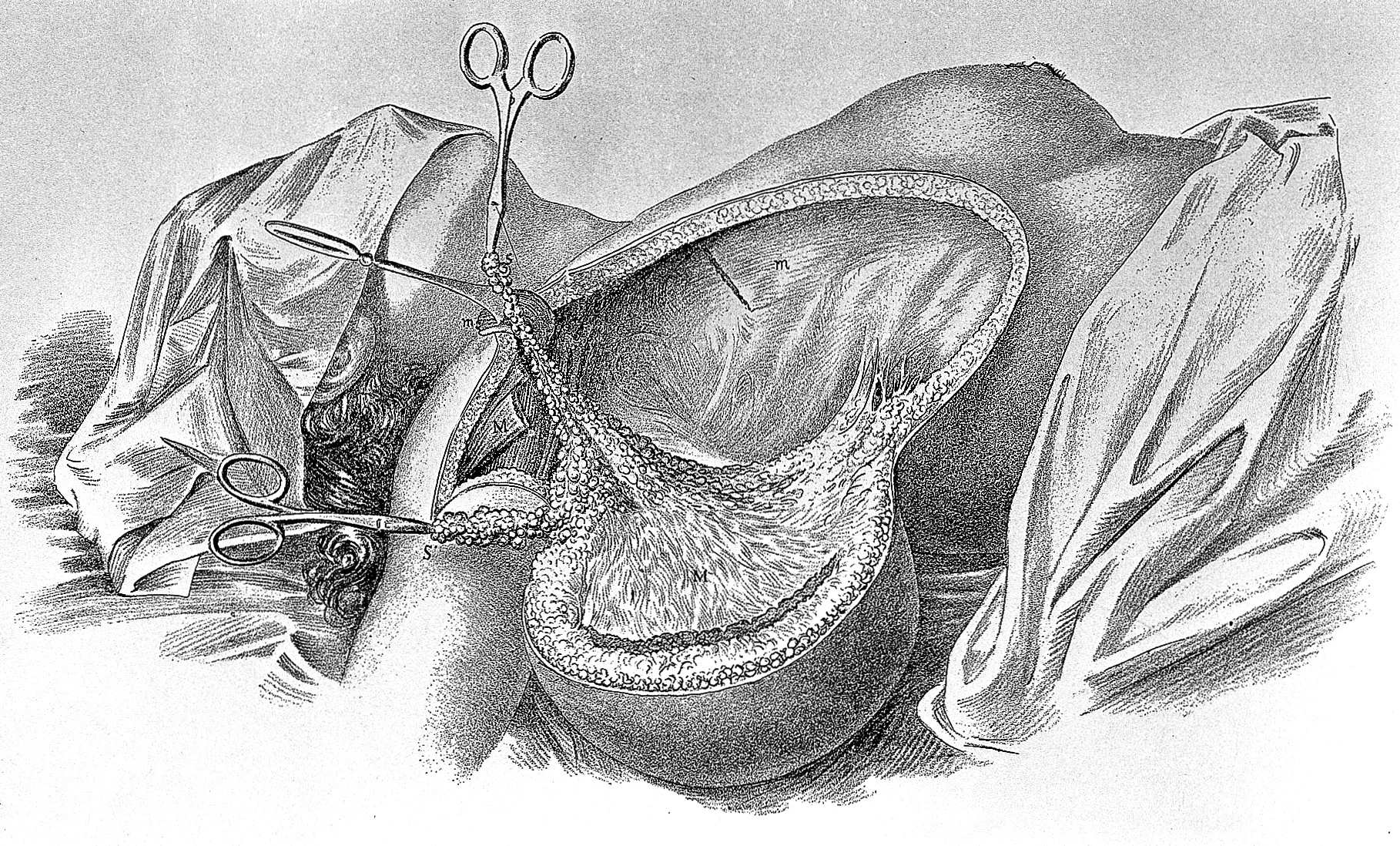

This European experience left a deep imprint. From this collective experience Halsted internalized a guiding principle—that surgery must be deliberate, thoughtful, and exacting, never hurried. Returning to America, he was determined to bring the precision of German surgical science into what was still, in Johns Hopkins and later many U.S. hospitals, more craft than discipline. At Johns Hopkins, Halsted introduced what became known as the Halstedian principles:

- meticulous control of bleeding

- absolute respect for tissues

- gentle handling with instruments instead of fingers

- and layer-by-layer wound closure

These sound obvious today, but at the time they were revolutionary. Surgeons began to see that patients could survive complex operations not just by luck, but by careful method.

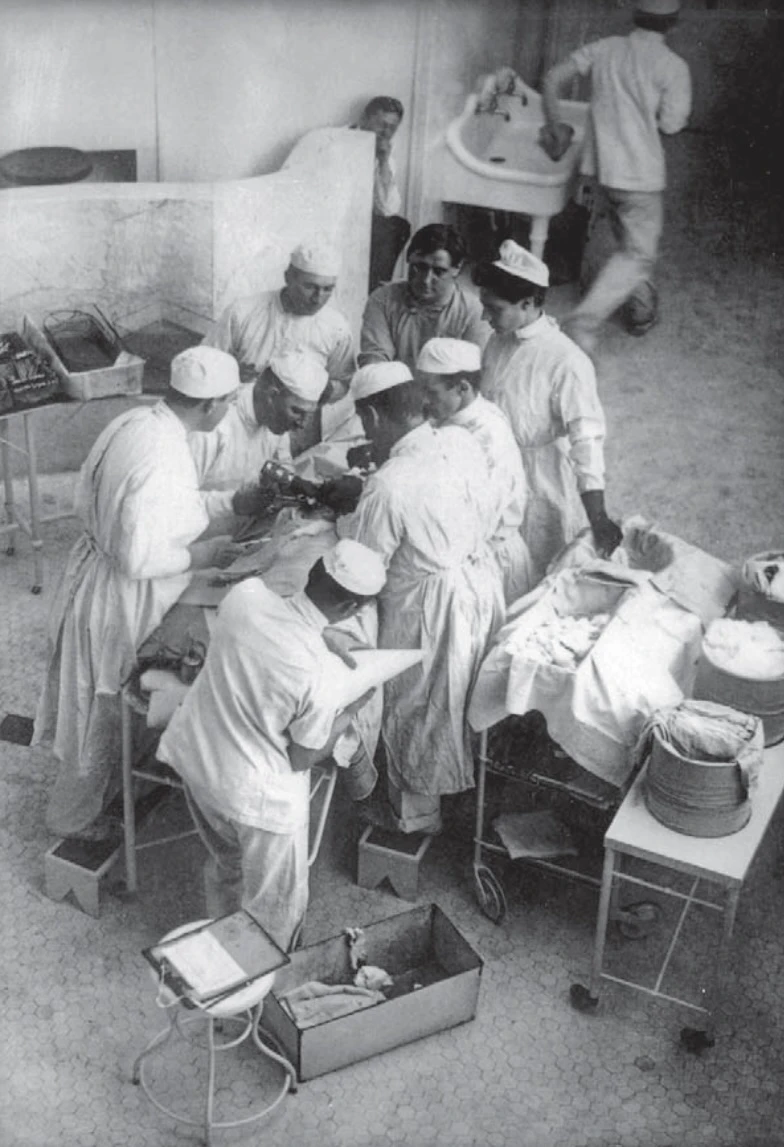

The Birth of American Surgical Training

Perhaps Halsted’s greatest gift was not just how he operated, but how he taught. Inspired by the structured clinics of Germany, he created the first surgical residency program in the United States. Surgeons in the 19th and early 20th century preferred private practice following short apprenticeship, thereby avoiding commitment to teaching and research. Lengthy training in the University hospitals was even called the 'dead men’s shoes' system because of the longer waiting time for free academical posts. Furthermore, they were often reluctant to train younger colleagues to avoid competition they would face from these physicians.

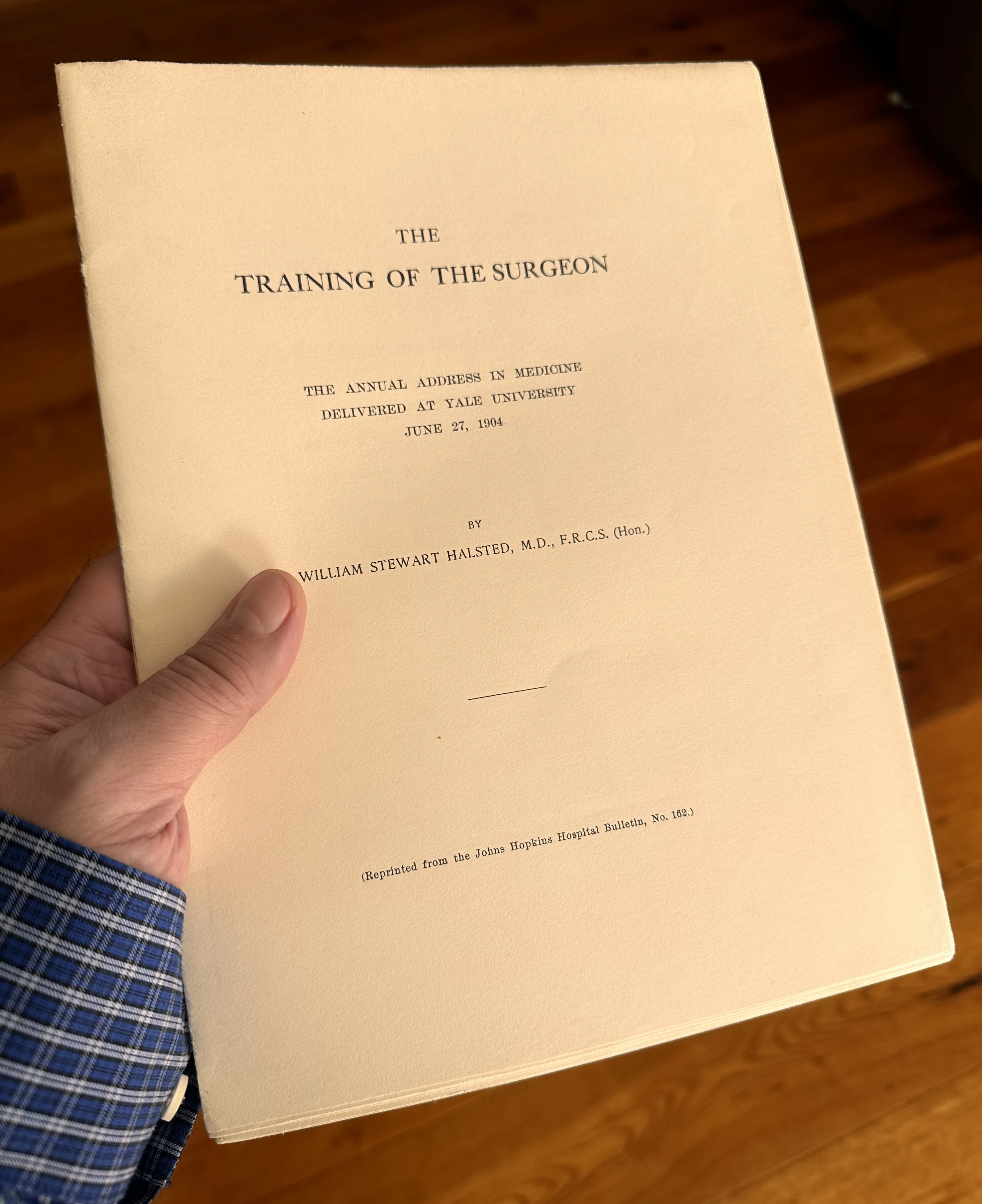

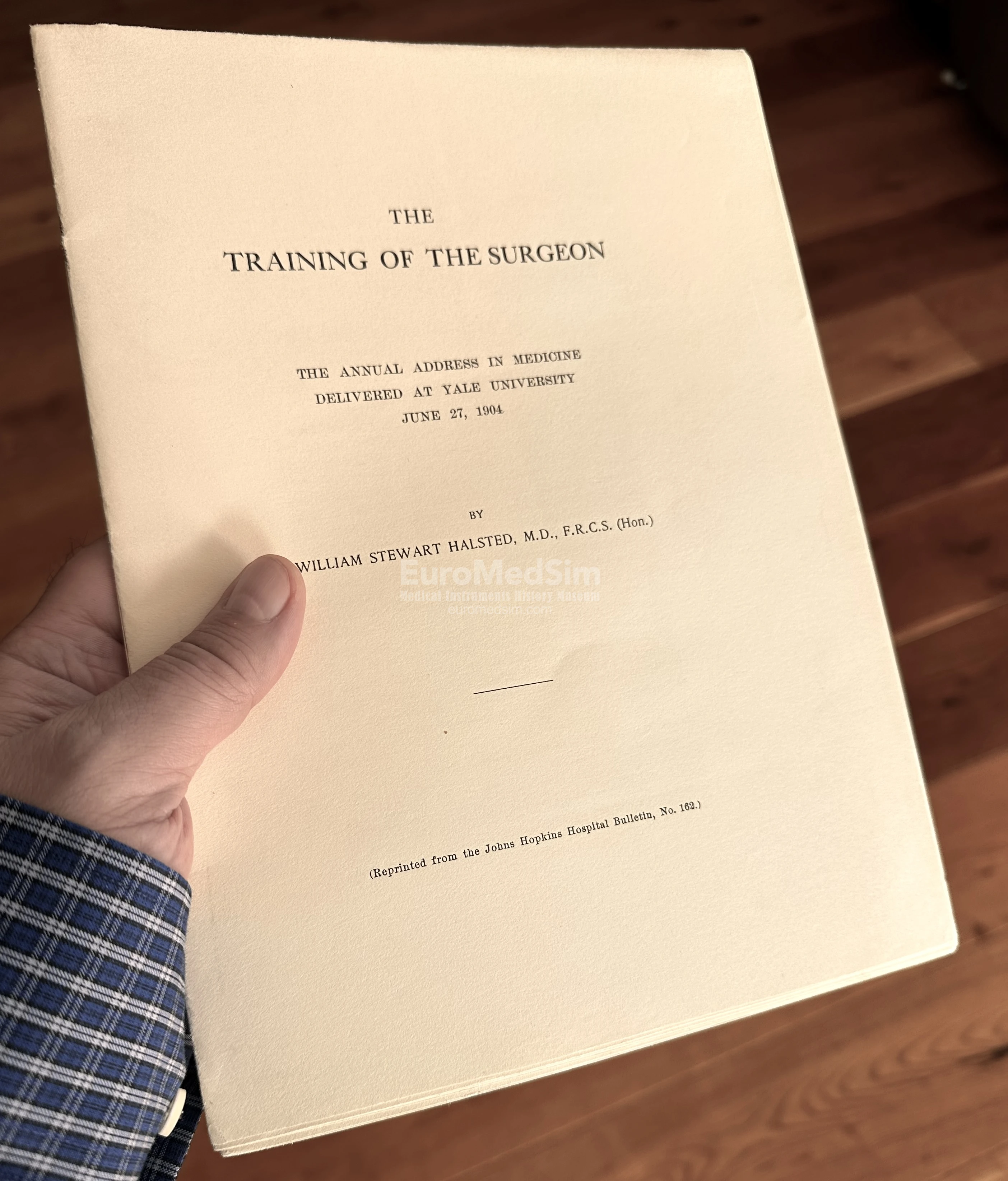

His 1904 Yale address “The Training of the Surgeon” emphasized that surgical skill must be built through rigorous, systematic training rather than quick apprenticeship. He argued for structured, carefully supervised residency programs, where surgeons-in-training would gradually assume responsibility while mastering both technical skill and scientific inquiry. This lecture laid the foundation for the modern surgical residency system in the United States.

"Unlike European system,... Halsted’s residency training programme produced surgeons with immediate career opportunities. His chief residents (those in charge of the assistant residents) trained for 8 years and his assistant residents for 1 year or more. After this time, many of them went on to become leaders in US surgery. Of 17 chief residents, seven became Professors of Surgery (Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Cornell, Virginia, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati), one became Surgeon-in- Chief in Detroit, and only four went into private practice." (Michael P Osborne, 2007)

Young doctors were no longer thrown straight into practice; instead, they advanced step by step, gaining responsibility only when proven ready. This system — 'see one, do one, teach one' — has remained the basis of surgeon training until recently, although it must be said that modern technologies are making their own adjustments. Today, the slogan is more like 'see one, sim one, do one.' And with the rapid implementation of virtual educational methods, it is possible that 'VR one' will soon push 'sim one' as well.

Stories Changed Surgery

One famous story reveals both Halsted’s sensitivity and his lasting impact. His scrub nurse — who later became his wife — developed severe dermatitis from the antiseptic solutions used in surgery. Halsted, unwilling to lose such a skilled assistant, approached the Goodyear Rubber Company with an odd request: custom-made rubber gloves. What began as a personal favor turned into one of the greatest safety innovations in surgical history.

Another story is darker. While experimenting with local anaesthesia, Halsted used himself as a subject, injecting cocaine. The habit spiraled into lifelong addiction, later managed with morphine. Yet despite these struggles, his contributions never wavered. He was proof that brilliance and frailty can coexist in one man.

William Halsted was not a flamboyant surgeon. He was quiet, exacting, even severe. But his methods reshaped surgery into something safer, more humane, more scientific. His German mentors gave him the foundation, and his American trainees carried his principles across the world. Every modern operating room — with its gloves, careful incisions, and rigorously trained residents — still echoes with the spirit of Halsted.