Tourniquet, principal instrument for bleeding control

6th–7th century BCE

Sushruta (about 600 BCE), an ancient surgeon lived in Kashi, India, is considering the first known surgeon in medical history. He has left the Sushruta Samhita, the oldest compilation of surgical texts, covering essential principles, pathology, anatomy, and surgical management (however, this document may, of course, be a compilation of texts by various authors who lived in different eras). Among the instruments illustrated in the later English translation of this work, there is no tourniquet, apparently it refers to descriptions of leather bands/ligatures applied on limb. We believe that this is probably not a reference to an instrument, but rather to a method of bandaging and tying off a limb, mentioned in Ayurvedic classics and other ancient sources when bitten by snakes to prevent the poison from spreading from the limb further into the body, rather than a method of haemorrhage control. In any way, this texts collection was known in Sanskrit for a long time, and even later Arabic translations (8th cent.) did not bring this method of haemostasis to European medicine.

Antiquity

The encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c. 25 BC – c. 50 AD), who compiled the knowledge of the ancients, and the prolific author and surgeon Galen, who had his own experience, mention amputations in their works, describing the course of the procedure and the necessary instruments. Although in the work De Medicina in Lib. VII, Cap. 33 (De gangraena — 'About gangrene'), where Celsus describes amputation, there is no mention of bandaging the limbs or ligating the vessels to stop bleeding, these descriptions are found in other sections: in Lib. VII, Caput XIX De testiculorum curationibus, et primo de incisione, et curatione inguinis vel scroti he wrote:

In quibus quum multae venae discurrant, tenuiores quidem praecidi protinus possunt: majores vero ante longiore lino deligandae sunt, ne periculose sanguinem fundant (... in the course of which many blood vessels are met with; the smaller ones can be summarily divided; but larger ones, to avoid dangerous bleeding, must be first tied with rather long flax thread).

And also this one: Lib V. Caput XXVI (p.21). De quinque generibus noxarum corporis et primo de vulneribus:

Quod si illa quoque profluvio vincuntur, venae quae sanguinem fundunt, apprehendendae, circaque id quod ictum est, duobus locis deligandae, intercidendaeque sunt, ut et in se ipsae coeant, et nihilominus ora praeclusa habeant. (Book V. Chapter XXVI (part 21). 'But if even these are powerless against the profuse bleeding, the blood-vessels which are pouring out blood are to be seized, and round the wounded spot they are to be tied in two places and cut across between so that the two ends coalesce each on itself and yet have their orifices closed.').

Thigh tourniquet, bronze. The straps have engraved patterns and originally the bronze would have been coated with leather to prevent damaging the skin of the patient. Ancient Rome, from the Collection of the Science Museum, London

Was it a tourniquet as we understand it today? Not yet, but all these items can be described as “constricting band” and “vessel ligation,” confidently asserting that stopping bleeding by tying off vessels and wrapping limbs by trauma or amputation was already invented and widely used in Ancient Rome. In any case, the discoverer of the methods has long been lost somewhere in the depths of previous centuries.

14 Century

The dark millennia following the fall of Rome left us with almost no written sources. The numerous kings, princes, and scheming clergymen, who were constantly at war with each other, had no time for the development of librarianship. Therefore, one of the first medieval works that has survived to this day is a manuscript by the French surgeon Guy de Chauliac (c. 1300–1368), who worked in Avignon, where the papal residence had been moved in those years. In his manuscript Chirurgia magna (1363, Avignon, France), he recommended wrapping a tight band below and above the site of amputation to reduce pain (sic!) and limit bleeding. It is worth noting that throughout the text, the author constantly refers to ancient authorities such as Hippocrates, Galen, Haly Abbas, Albucasis, and Al-Razi in his book. Although this illustrated manuscript became widely known, it is evident that the compression bandage technique was so imperfect that, to ensure haemostasis, surgeons preferred to additionally cauterize the wound with a red-hot iron, leaving a charred scab on the stump.

Miniature from the manuscript 'La Grande Chirurgie' by Guy de Chauliac, 1363 (beginning of the Treatise on Wounds, fol. 66), French National Library

.

16 century

Hans Gersdorff (1455–1529), a German surgeon from Strasbourg wrote a 'Feldtbuch der Wundartzney' (Field-Manual on Wound Treatment), a practical guide, although largely based on the 'Chirurgia Magna' by Guy de Chauliac (1298–1368), dispelling a number of outdated misconceptions. The Feldbuch became famous primarily for its description of amputations — Gersdorff himself claimed to have performed more than 200 such operations. The book is famous for its numerous vivid woodcuts, among them is a depiction of the amputation — Serratura (page LXIXr, the copy of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München).

Woodcut depicts an amputation: two bands tied in knots are applied to the operated leg — above and below the point of section of the lower limb. Hans Gersdorff, Feldtbuch der Wundartzney, 1517. Copy of the Bavarian State Library, Munich.

17 century. 'Stick-and-Band'

Stopping bleeding from wounds on the battlefield, as well as during amputations in the field, required a new, faster, and more effective method. Such a method was found—it consisted of using a rope (or leather strap) with a wooden stick threaded between the rope and the limb or through a knot. When the stick was turned, it tightened around the limb, stopping the bleeding of the wounded soldier. Since that moment, this haemostatic device has probably started to be called a 'tourniquet' (in French, tourner – 'turn, rotate').

This simple but very effective 'Stick-and-Band' principle became one of the most important life-saving devices in the history of warfare, saving countless lives on the battlefields from the 17th century to modern conflict zones.

One of the surgeons credited with inventing (or describing) a new method of tightening a tourniquet using a rotating stick was German surgeon Wilhelm Fabry von Hilden or in Latin transcription Guilhelmus Fabricius Hildanus (1540–1644), who described various limbs amputations, including above the knee and elbow joints considered very risky (1620 and 1646). In particular, Fabry discouraged the method of amputation using a guillotine and cutting forceps, as this inevitably resulted in bone fractures — which was popular in that times.

He methodically explained how to pull back the soft tissues using ropes and sheep leather trousers so that the bone would be cut as close to the joint as possible and the remaining soft tissues could form a stump. Once the flesh had been quickly cut and the periosteum separated, the edge of the trousers was passed over the incision, both straps were pulled tight, and the flesh was pulled up so that the saw could be applied to the bone as high as possible.

The same cord was used to block the arteries and veins to reduce blood loss, as well as to compress the nerves so that the leg would become numb and less sensitive. In addition to haemostasis with a red-hot iron to save time, he also recommended the ligature method — the vessels were grasped with special forceps, pulled slightly out of the wound, and tied with double hemp threads.

Note how in the figure below, the assistant, passing additional straps through the tourniquet on the thigh, carefully pulls the soft tissue upward.

Amputation scene. , from the book 'De gangraena et sphacelo, tractatus methodicus' by Wilhelm Fabricius Hildanus [1620?]. Source: Wellcome Collection

Another name associated with the use of this method was Étienne Morel (1648–1710), a renowned French military surgeon who, according to another widely circulated version cited in various journal articles, was the first to use a tourniquet proximal to the wound to stop bleeding on the battlefield during the Siege of Besançon in 1674. However, it was merely an invention but modification of the method (which was already known as the 'Spanish Windlass'). Morel suggested placing a small pad under the rope where it passed over the major vessels, which enhanced the haemostatic effect. Unfortunately, after the procedure was completed and the tourniquet was removed, bleeding could resume, it was difficult to control it again, and this could lead to fatal consequences [John Kirkup, 2016].

18 Century

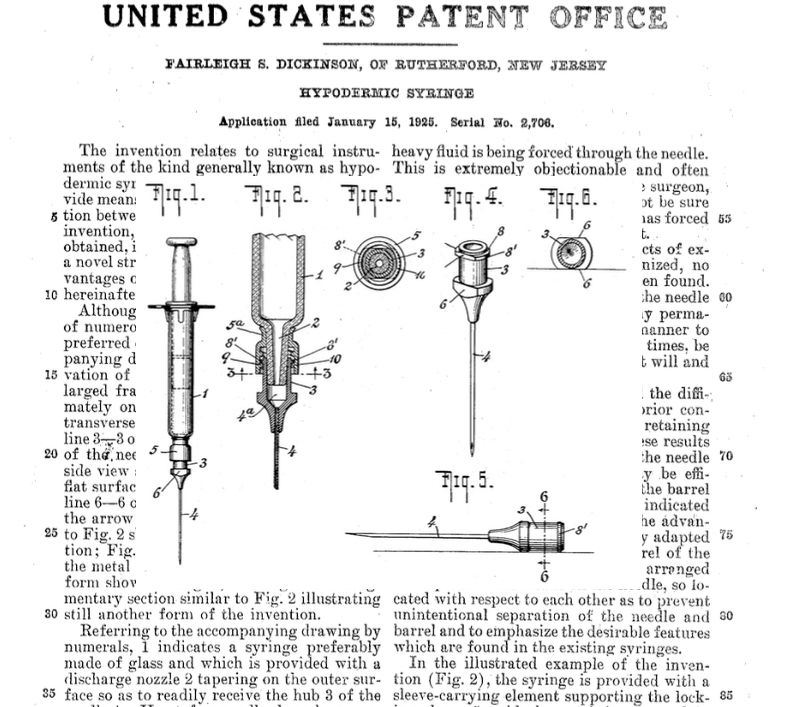

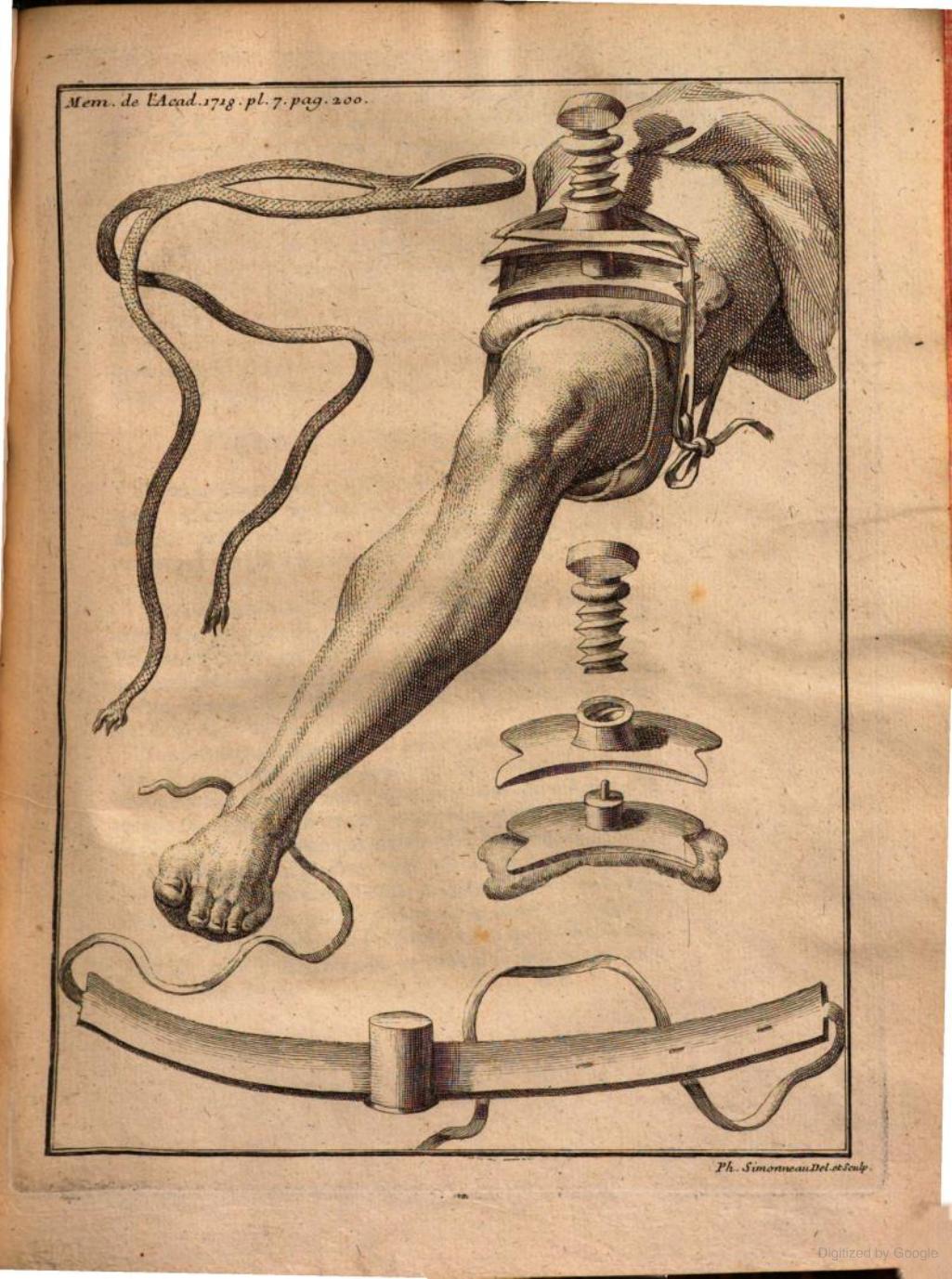

Shortly before the invention of Petit (see below) a prominent French court surgeon and anatomist, First Surgeon to the Dauphin's children Pierre Dionis (1643–1718) in his influential surgical textbook Cours d'opérations de chirurgie démontrées au Jardin royal (Paris, 1714) has given illustration of the instruments necessary for amputation (fig. XLVII facing p. 611). Among knives and saws one can see a circular bandage with knots holding two wooden handles, which can be tightened on the wound by twisting them. It is noteworthy that iron cauters for burning blood vessels are missing and replaced by forceps coiled with thread and a needle for ligating blood vessels for haemostasis.

Fig. 47. Instruments for amputation. Band (G) and two handles (H) to tighten it by rotation. Illustration from the book 'Cours d'operations de chirurgie : demontrées au Jardin royal ...' . Pierre Dionis, 1714. Source: Wellcome Collection

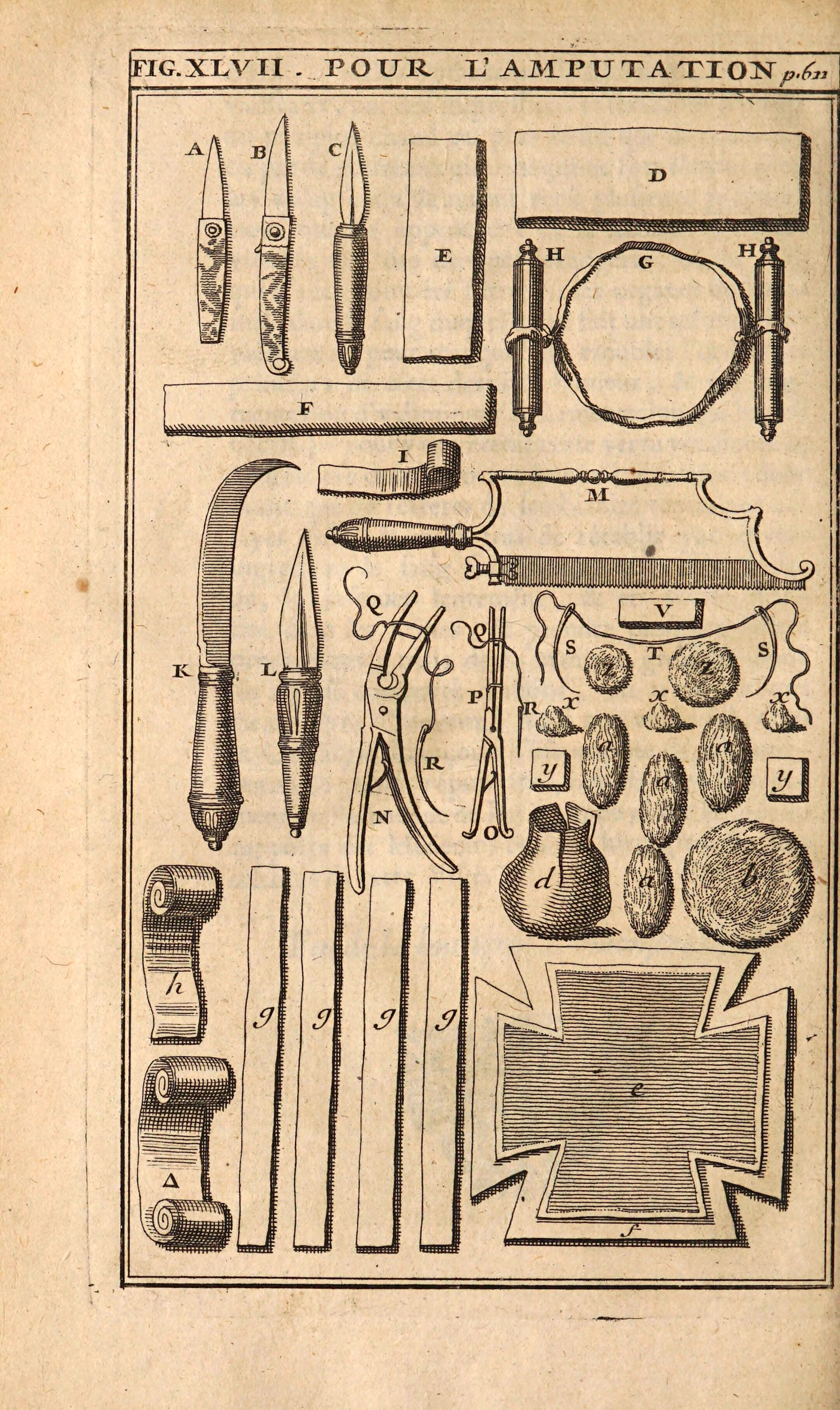

A truly technological innovation, the pride of French surgery, was the invention of the screw-type hemostatic bandage, which eventually became known as the tourniquet. French surgeon Jean-Louis Petit (1674-1750) invented a device whose tension is adjusted by a rotating screw. Its design remained the standard for about 200 years. The main components were a wide strap (linen/canvas/leather) with a buckle, the teeth of which dug into the fabric when tightened and secured it, and a screw with a T-shaped handle (usually brass, sometimes wooden). At the opposite side from the tensioning system with the screw, a tightly stuffed leather cushion, pressure pad ('pelotta') was attached to a small frame. When applying the tourniquet, the pelotta should be placed on skin directly above the large artery (e.g. femoral artery as depicted below). When the screw is turned, the distance between the two metal plates increases, causing the strap to tighten and press the pad firmly against the artery, stopping the blood flow. The screw not only allows the tension to be adjusted, but also ensures convenient operation without an assistant.

Tourniquet invented and described by Jean-Louis Petit, depicted construction and medical application. HISTOIRE DE L'ACADEMIE ROYALE DES SCIENCES. Année M. DCCXVIII. Illustration on the Pl. 7 at the non-numerated page between p.200 and p.201. Source: Source: Google Books. Original: National Library of the Czech Republic

On 21 January 1718, in the publication Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, he wrote: "... The [old] tourniquet is simply a leather band or strap that is wrapped around the limb, loosely enough to allow a stick or drum to be inserted, and thus tighten the limb as much as necessary to prevent blood from flowing through it. This deprives the limb of circulation, allowing surgery to be performed without fear of hemorrhage. The instrument [had] disadvantages, namely: ... often pinches the patient's skin, causing very sharp pains, sometimes as severe as those of the operation itself; ... the compression is applied equally around the entire circumference, without distinction, which is as unnecessary as it is dangerous: the parts that do not need to be compressed suffer unnecessarily, and the skin is bruised; someone is needed to hold the tourniquet while the surgeon operates."

Further he continued with listing the advantages of his invention: "... it compresses only where necessary and leaves the other parts free; it does not cause injury or pain; it suspends circulation as reliably as an ordinary tourniquet, without any of its drawbacks... Once it has been applied, the pressure can be increased or decreased at will, as many times as deemed necessary, without having to remove it; a single person can use it without the help of an assistant, which makes operations easier and safer. ... the instrument can be left on the area for some time, without discomfort or pain to the patient, in order to ensure compression."

Description of its new construction was given as following: "This screw is contained in a solid body, in which it acts on a plate that compresses the area; the whole thing is so simply arranged that it can be made of wood if iron is not available (in original: 'qu’on peut le faire de bois, si l’on manque de fer'). ... it stops the blood very reliably, without causing pain, without needing assistance, and without damaging the soft tissues; thus it makes operations safer, quicker, and more humane." [Jean-Louis Petit, 1718]

Its discovery was prompted, in particular, by the sensational clinical case of the Marquis de Rotelin's thigh amputation, which was complicated by uncontrollable bleeding. At that time, Petit commissioned a “skilled mechanic,” Mr. Perron, to make a tourniquet overnight. The carving, screw, and plates of this first tourniquet were made of wood, which explains why he was able to make it in one night.

Interestingly, although the term tourniquet is a French word and was proposed by a French inventor, French surgeons themselves prefer the word garrot, which comes from the word garrotter (to strangle) [John Kirkup, 2007].

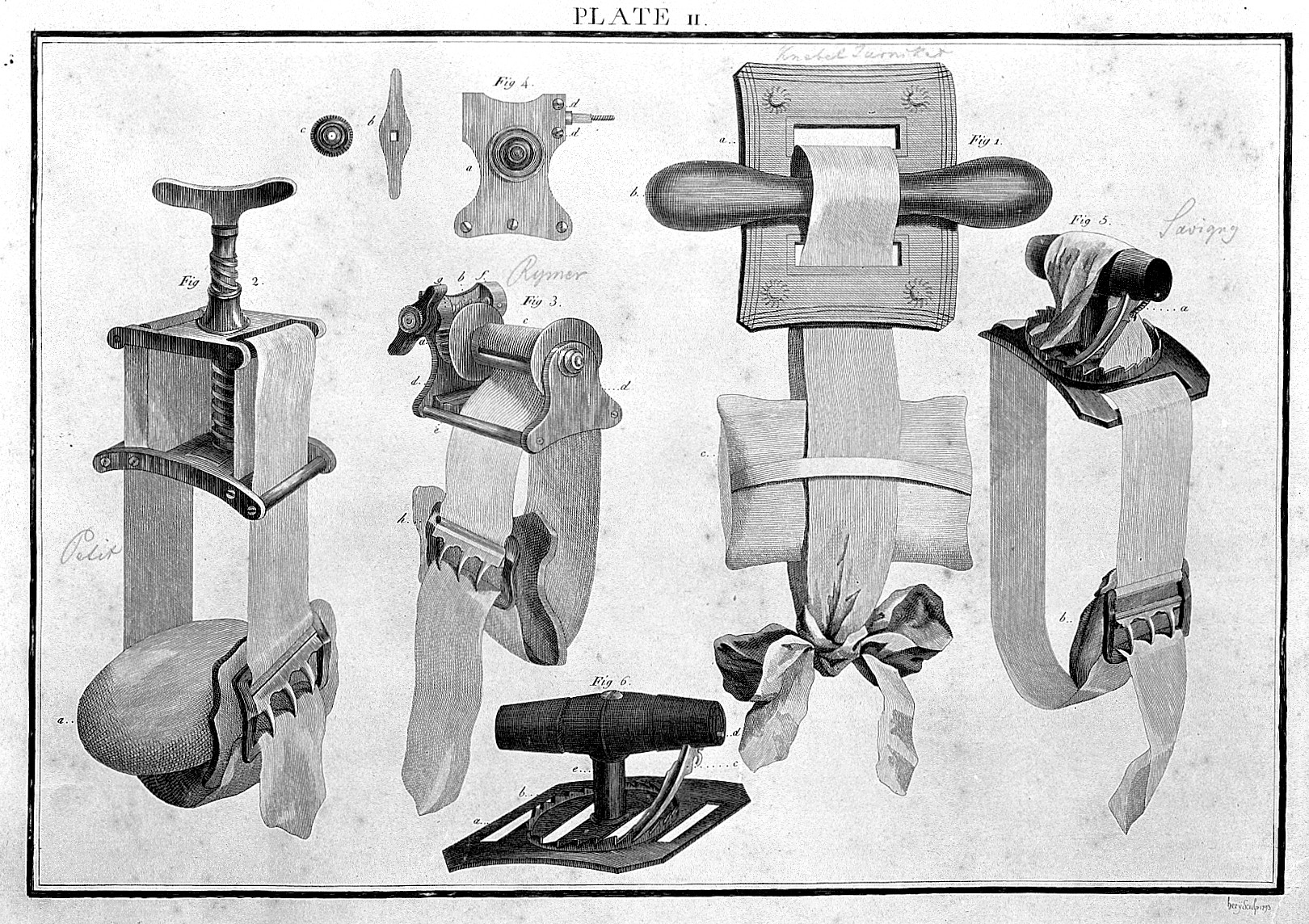

En engraving with different types of tourniquets from "A collection of engravings, representing the most modern and approved instruments used in the practice of surgery : With appropriate explanations / By J.H. Savigny, surgeon's instrument-maker., Savigny, J. (John). 1798. Source: via wikipedia from the Wellcome Collection.

19 century

Even though there were numerous improvements done, the Petit's screw tourniquet was remaining a golden standard almost two centuries and was used worldwide. During the American Civil War, more than 50.000 field (strap) tourniquets and 13.000 Petit screw tourniquets were used in the performance of more than 29.000 amputations by surgeons of the US Army Medical Department [Alan J Hawk, 2016].

1873 — Esmarch bandage. Friedrich von Esmarch introduces elastic bandage wrapping to exsanguinate a limb before applying a tourniquet; this ushers in bloodless-field surgery practices.

20-21 centuries

1904 — Pneumatic tourniquet. Harvey Cushing publishes on inflatable (air-cuff) tourniquets—an important step toward modern OR cuffs.

1908 — Bier block & exsanguination refinement. August Bier describes IV regional anesthesia using Esmarch-style exsanguination with tourniquet control.

2000s — Modern windlass field tourniquets. The Combat Application Tourniquet (C-A-T) becomes the U.S. Army’s official tourniquet (from 2005), central to TCCC doctrine during Iraq/Afghanistan; strong survival data emerge in 2008–2009 military studies (e.g., Kragh et al.).

2015→ — Civilian adoption. The Stop the Bleed campaign spreads tourniquet training to the public, codifying lessons from TCCC.

Literature

Hawk AJ. ArtiFacts: Jean Louis Petit's Screw Tourniquet. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016 Dec;474(12):2577-2579. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-5042-6. Epub 2016 Aug 25. PMID: 27562790; PMCID: PMC5085941.

Kirkup, John. Who made what? Petit's screw tourniquet. J Med Biogr. 2007 May;15(2):67. doi: 10.1258/j.jmb.2007.05-75. PMID: 17551602.

Petit, Jean-Louis. D'UN NOUVEL INSTRUMENT DE CHIRURGIE Par M. Petit, Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences, avec les mémoires de mathématique & de physique, 1718

Renne, Claude. À propos du tourniquet de Jean-Louis Petit. HISTOIRE DES SCIENCES MEDICALES - TOME XLVIII - N° 1 - 2014, p. 125

Reference objects

Tourniquet of Petit's type, 19 c., Wellcome collection of the Science Museum, London